![]()

V

Logic and Reality

How are the rules of deduction to be justified? Any argument for them presumes them, and so begs the question. Susan Haack identifies two responses to this quandary: the pessimistic approach that views deduction as unjustified and the optimistic approach that views deduction as needing no justification.

How are counterfactual claims to be understood? Much of our everyday reasoning involves judgments of the form, had p occurred, then q would have resulted. Nelson Goodman surveys and tries to resolve the many problems that such conditionals pose.

How is the existential quantifier to be understood? For example, does the statement Pegasus does not exist seem to imply, paradoxically, that there is a Pegasus? Willard V. Quine rejects this view, arguing that “To be is to be the value of a variable.”

![]()

13

The Justification of Deduction

Susan Haack

(1) It is often taken for granted by writers who propose—and, for that matter, by writers who oppose—‘justifications’ of induction, that deduction either does not need, or can readily be provided with, justification. The purpose of this paper is to argue that, contrary to this common opinion, problems analogous to those which, notoriously, arise in the attempt to justify induction, also arise in the attempt to justify deduction.

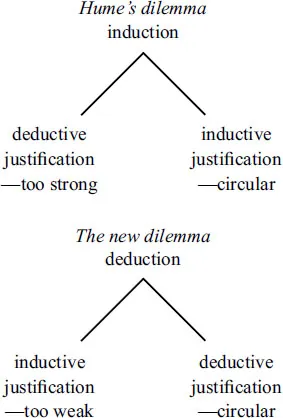

Hume presented us with a dilemma: we cannot justify induction deductively, because to do so would be to show that whenever the premisses of an inductive argument are true, the conclusion must be true too—which would be too strong; and we cannot justify induction inductively, either, because such a ‘justification’ would be circular. I propose another dilemma: we cannot justify deduction inductively, because to do so would be, at best, to show that usually, when the premisses of a deductive argument are true, the conclusion is true too—which would be too weak; and we cannot justify deduction deductively, either, because such a justification would be circular.

The parallel between the old and the new dilemmas can be illustrated thus:

(2) A necessary preliminary to serious discussion of the problems of justifying induction/deduction is a clear statement of them.

This means, first, giving some kind of characterisation of ‘inductive argument’ and ‘deductive argument.’ This is a more difficult task than seems to be generally appreciated. It will hardly do, for example, to characterise deductive arguments as ‘non-ampliative’ (Salmon [1966]) or ‘explicative’ (Barker [1965]), and inductive arguments as ‘ampliative’ or ‘non-explicative’; for these characteristics are apt to turn out either false, if the key notion of ‘containing nothing in the conclusion not already contained in the premisses’ is taken literally, or trivial, if it is not.

Because of the difficulties of demarcating ‘inductive’ and ‘deductive’ inference, it seems more profitable to define an argument:

An argument is a sequence A1 … An of sentences (n ≥ I), of which A1 … An –1 are the premisses and An is the conclusion—and then to try to distinguish inductive from deductive standards of a ‘good argument.’

It is well known that deductive standards of validity may be put in either of two ways: syntactically or semantically. So:

D1 | An argument A1 … An–1 ├ An is deductively valid (in LD) just in case the conclusion, An, is deducible from the premisses, A1 … An–1 and the axioms of LD if any, in virtue of the rules of inference of LD (the syntactic definition). |

D2 | An argument A1 … An–1 ├ An is deductively valid just in case it is impossible that the premisses, A1 … An–1, should be true, and the conclusion, An, false (the semantic definition). |

Similarly, we can express standards of inductive strength either syntactically or semantically; the syntactic definition would follow D1 but with ‘L1’ for ‘LD’; the semantic definition would follow D2 but with ‘it is improbable, given that the premisses are true, that the conclusion is false.’

The question now arises, which of these kinds of characterisation should we adopt in our statement of the problems of justifying deduction/induction? This presents a difficulty. If we adopt semantic accounts of deductive validity/inductive strength, the problem of justification will seem to have been trivialised. The justification problem will reappear, however, in a disguised form, as the question ‘Are there any deductively valid/inductively strong arguments?’. If, on the other hand, we adopt syntactic accounts of deductive validity/inductive strength, the nature of the justification problem is clear: to show that arguments which are deductively valid/inductively strong are also truth-preserving/truth-preserving most of the time (i.e. deductively valid/inductively strong on the semantic accounts). On the other hand, there is the difficulty that we must somehow specify which systems are possible values of ‘LD’ and ‘L1,’ and this will presumably require appeal to inevitably vague considerations concerning the intentions of the authors of a formal system.

A convenient compromise is this. There are certain forms of inference, such as the rule:

R1 | From: m/n of all observed F’s have been G’s to infer: m/n of all F’s are G’s |

which are commonly taken to be inductively strong, and similarly, certain forms of inference, such as

MPP | From: A ⊃ B, A to infer: B |

which are generally taken to be deductively valid. Analogues of the general justification problems can now be set up as follows:

the problem of the justification of induction: show that RI is truth-preserving most of the time.

the problem of the justification of deduction: show that MPP is truth-preserving.

My procedure will be, then, to show that difficulties arise in the attempt to justify MPP which are analogous to notorious difficulties arising in the attempt to justify RI.

(3) I consider first the suggestion that deduction needs no justification, that the call for a proof that MPP is truth-preserving is somehow misguided.

An argument for this position might go as follows:

It is analytic that a deductively valid argument is truth-preserving, for by ‘valid’ we mean ‘argument whose premisses could not be true without its conclusion being true too.’ So there can be no serious question whether a deductively valid argument is truth-preserving.

It seems clear enough that anyone who argued like this would be the victim of a confusion. Agreed, if we adopt a semantic definition of ‘deductively valid’ it follows immediately that deductively valid arguments are truth-preserving. But the problem was, to show that a particular form of argument, a form deductively valid in the syntactic sense, is truth-preserving; and this is a genuine problem, which has simply been evaded. Similar arguments show the claim, made e.g. by Strawson in [1952], p. 257, that induction needs no justification, to be confused.

(4) I argued in Section (1) that ‘justifications’ of deduction are liable either to be inductive and too weak, or to be deductive and circular. The former, inductive kind of justification has enjoyed little popularity (except with the Intuitionists? cf. Brouwer [1952]). But arguments of the second kind are not hard to find.

(a) Consider the following attempt to justify MPP:

A1 | Suppose that ‘A’ is true, and that ‘A ⊃ B’ is true. By the truth-table for ‘⊃,’ if ‘A’ is true and ‘A ⊃ B’ is true, then ‘B’ is true too. So ‘B’ must be true too. |

This argument has a serious drawback: it is of the very form which it is supposed to justify. For it goes:

A1’ | Suppose C (that ‘A’ is true and that ‘A ⊃ B’ is true). If C then D (if ‘A’ is true and ‘A ⊃ B’ is true, ‘B’ is true). So, D (‘B’ is true too). |

The analogy with Black’s ‘self-supporting’ argument for induction [1954] is striking. Black proposes to support induction by means of the argument:

A2 | RI has usually been successful in observed instances. ∴ RI is usually successful. |

He defends himself against the charge of circularity by pointing out that this argument is not a simple case of question-begging: it does not contain its conclusion as a premiss. It might, similarly, be pointed out that A1’ is not a simple case of question-begging: for it does not contain its conclusion as a premiss, either.

One is inclined to feel that A2 is objectionably circular, in spite of Black’s defence; and this intuition can be supported by an argument, like Salmon’s [1966], to show that if A2 supports RI, an exactly analogous argument would support a counter-inductive rule, say:

RCI | From: most observed F’s have not been G’s to infer: most F’s are G’s. |

Thus,

A3 | RCI has usually been unsuccessful in the past. ∴ RCI is usually successful. |

In a similar way, one can support the intuition that there is something wrong with A1’, in spite of its not being straightforwardly question-begging, by showing that if A1’ supports MPP, an exactly analogous argument would support a deductively invalid rule, say:

MM (modus morons);

From: A ⊃ B and B

to infer: A.

Thus:

A4 | Supposing that ‘A ⊃ B’ is true and ‘B’ is true, ‘A ⊃ B’ is true ⊃ ‘B’ is true. Now, by the truth-table for ‘⊃,’ if ‘A’ is true, then, if ‘A ⊃ B’ is true, ‘B’ is true. Therefore, ‘A’ is true. |

This argument, like A1, has the very form which it is supposed to justify. For it goes:

A4’ | Suppose D (if ‘A ⊃ B’ is true, ‘B’ is true). If C, then D (if ‘A’ is true, then, if ‘A ⊃ B’ is true, ‘B’ is true). So, C (‘A’ is true). |

It is no good to protest that A4’ does not justify modus morons because it uses an invalid rule of inference, whereas A1’ does justify modus ponens, because it uses a valid rule of inference—for to justify our conviction that MPP is valid and MM is not is precisely what is at issue.

Neither is it any use to protest that A1’1 is not circular because it is an argument in the meta-language, whereas the rule which it is supposed to justify is a rule in the object language. For the attempt to save the argument for RI by taking it as a proof, on level 2, of a rule of level 1, also falls prey to the difficulty that we could with equal justice give a counter-inductive argument, on level 2, for the counter-inductive rule at level 1. And similarly, if we may give an argument using MPP, at level 2, to support the rule MPP at level 1, we could, equally, give an argument, using MM, at level 2, to support the rule MM at level 1.

(b) Another way to try to justify MPP, which promises not to be vulnerable to the difficulty that, if it is acceptable, so is an analogous justification of MM, is suggested by Thomson’s discussion [1963] of the Tortoise’s argument. Carroll’s tortoise, in [1895], refuses to draw the conclusion, ‘B,’ from ‘A ⊃ B’ and ‘A,’ insisting that a new premiss, ‘A ⊃ ((A ⊃ B) ⊃ B)’ be added; and when that premiss is granted him, will still not draw the conclusion, but insists on a further premiss, and so ad ...