![]()

CHAPTER 1

Origins, then 1925-1945

The Paterno clan originated with an immigrant from South China, Ming Mong Lo. He arrived in Manila circa 1760, and easily assimilated himself into the local society not too long after his arrival. He was baptized Jose Molo and married a Filipina of Malay origin, with the family name of Agustin, or San Agustin. They had five children; one of them, Paterno Molo Agustin, became a successful businessman. Paterno’s children adopted their father’s full name as their own family name. One of the sons, Maximo M(olo) A(gustin) Paterno was even more successful in business than his father. My great grandfather, Lucas, was a brother of Maximo. Thus I am counted among the clan’s sixth generation.

Paterno Molo’s progeny resided in various parts of Manila, namely the Parian, Binondo, Sta. Cruz, and Quiapo districts. The Lucas branch of the clan (my great grandfather’s family) resided mostly in Quiapo, a district at the center of the city of Manila.

Until the late 1960s, Quiapo, its two adjoining districts—Santa Cruz and Binondo—and immediate vicinities Avenida Rizal and Escolta—were considered the “old downtown” of the city. They were the center of higher education, entertainment, the arts, and of elite residences. My siblings and I were born and lived in Quiapo, on Mendoza Street, a side street of R. Hidalgo, which connects two famous churches, Quiapo and San Sebastian. An end terminal of the Meralco tranvia (streetcar) was on the Quiapo side of R. Hidalgo until the tranvia line was dismantled in 1945.

By the 1970s, Quiapo had become part of the much deteriorated inner city of Manila. Its deterioration was accelerated by the first Light Rail Transit Line on Rizal Avenue. All of us siblings left Quiapo to reside in other parts of Metro Manila; one brother emigrated and lived in the US west coast for many years.

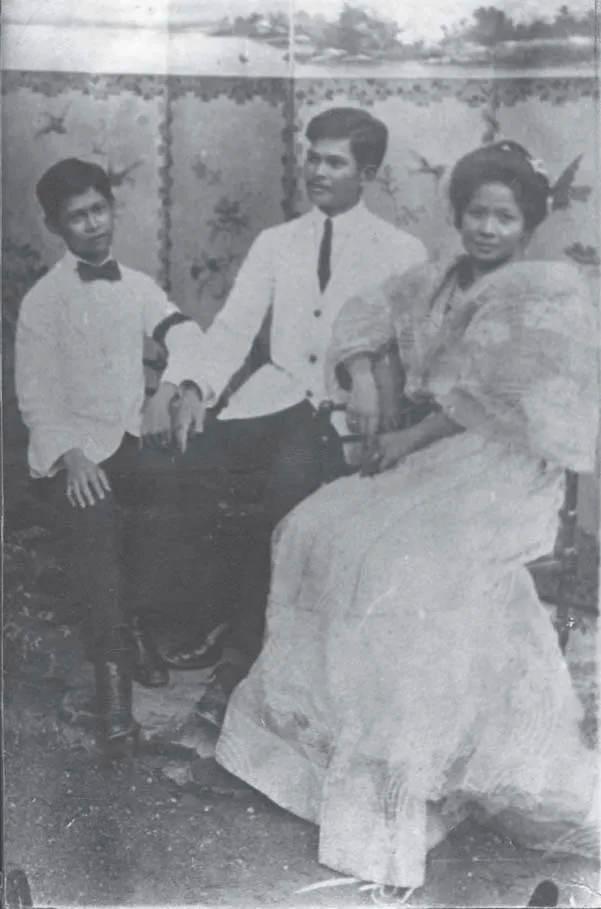

Fifth generation siblings. From left to right: Simon, Jose, Susana.

My paternal grandfather, Jose Maria Zamora Paterno, was one of the sons of Lucas. He had a business education—a perito mercantile degree—but he seemed uninterested in commerce. He loved to hunt for deer and wild boar, in the virgin forests of the Sierra Madre mountains, the eastern spine of Luzon island. On these hunting trips, he met and wooed Dolores Valera Ramos, a teacher. They were blessed with three children—Susana, my father Jose, and Simon. The family lived in Pangil, Laguna for about twelve years until Dolores died. They then moved to Jose Maria’s house at 130 Mendoza Street, and lived there for many years. That house was inherited by my father after Tia Susana got married and Tio Simon left to live and work in Cebu. My siblings and I were born in that house.

My maternal grandfather, Fausto Tirona, came from a Cavite family of teachers. A street in Imus, Cavite, which links the public market to the church, still bears the name of Maestro Fausto. My mother’s ancestral house is on that street. Fausto’s wife, Juana Casimiro, was of peasant stock from the Imus barrio of Malagasang. Her brother, a soldier in the Spanish military, won a posthumous medal for bravery, as well as a pension for fighting off a Moro assault on Zamboanga City. In his honor, my grandmother, Juana Casimiro, was known in her Barrio Malagasang as “Juana Caballero,” sister of a knight.

My father received his medical education at University of Sto. Tomas and practiced his profession for about ten years. In late 1924 he met and courted Jacoba Tirona. She was then dean of dormitory of Philippine Women’s College (now Philippine Women’s University or PWU). I remember snatches of her friends’ stories that they saw my father as a romantic figure, who came courting in the evenings riding a white horse through the streets of the city. He was thirty-six years of age; she was thirty-one.

Mama loved to tell her children how well she was taught by the Thomasites, so well that she was recruited to teach elementary school after completing Grade 7 at fourteen years old. She rose through the ranks of public school educators to become a supervising teacher and a principal. Thereafter, she joined Philippine Women’s College, founded by her cousin Francisca Tirona Benitez, as Dean of Dormitory.

By the time she and Papa met, Mama had already been a professional for seventeen years. The courtship did not take long, they were both ready to found their family. They married in February 1925, and she left her college post to become a full-time housewife and mother.

Jacoba Tirona Paterno talks to her son in their residence at 130 Mendoza St., Quiapo

Jacoba Tirona Paterno, ca. 1968

I am the first child of Jose P. Paterno and Jacoba Encarnacion Tirona, born on November 18, 1925, in the house they inherited from my grandfather, Jose Maria, at 130 Mendoza Street, Quiapo, Manila. All of us five siblings were born in that house. It was a wooden house, probably built by my grandfather. When it had become too small for our family, my parents built a three-story house, also of wood, beside it. All five children occupied the second floor, connected by a short stairway to the dining room of the old house. The third floor was the bedroom of our parents, except that when Papa was away, which was much of the time, Mama slept with the children on the second floor. The ground floor served as an office and guest quarters for relatives and other visitors from the province.

In the year after I was born, Tia Susana asked my father to join her husband, Vicente Madrigal, in his rapidly growing business. Although he already had an active medical practice, Papa was not able to refuse. His sister had been surrogate mother to Tio Simon and to him since she was twelve years old. She had been their main financial support, using her training and skills for a couturier business which sent her two brothers through high school and college. An indication of my father’s deep love and high regard for his Ate Sanang is found in the names he assigned at baptism to his two eldest born: to my sister—Susana, and to me—Vicente, after Tia Susana’s husband.

Mama must have had reservations about Papa’s change of occupation. After all, he was asked to leave the profession he had studied and was trained for, as well as the clientele he had accumulated during his decade-long medical practice. He would be engaged in work he had not trained for and the future of his family would be hostage to his in-laws. But with little evident hesitation, Papa turned over his medical practice to a doctor friend, and shortly embarked on his new work.

SCHOOLING

My memories of childhood and the preteen years are vague. Mother was the family’s dominant figure then. Father was busy in his work, away much of the time and not wont to engage his children in conversation. Mama’s background as a teacher was apparent in the way she raised her children and dealt with the household help and her few other employees. Advice she gave me as a child remained with me throughout my life. It may have referred to my father’s leaving his profession—do not depend on others, always maintain your independence.

Mama came from a family of three girls and two boys. The two eldest, Cristina and Mariano, never married. Gregoria became a nurse and married Francisco Galang, a civil servant who rose to become a director of the Bureau of Plant Industry. They had eight children. Constantino was a lawyer. He joined the US embassy staff and was an avid golfer. Since Mama had married at age thirty-two, and was the youngest of the brood, our Tirona cousins were mostly older than my siblings and me.

The cousins who were close in age to my sister Chuchi and me were the two youngest of the Madrigals, Jose (Belec) and Ising. I have few memories of visits to the Madrigal house on Gen. Luna Street in Paco, including a few weeks stay there during a European trip of the three eldest Madrigal girls, with my father as their chaperone. Chuchi was friendly with the youngest Madrigal child, Ising. At our visits to their house, we were always made welcome by our Tia Susana. After she died in 1940, we rarely visited the Madrigal house.

The Paterno elder to whom Mama was closest was my father’s aunt Maria Patrocinio, our Lola Mariquita. Her house on R. Hidalgo was accessed by a narrow pathway through the adjoining lot from our house. Mama learned stories about the Paterno extended family from Lola Quita. She would eventually will to our parents the 8,000 sq.m. lot, on a part of which my wife and I would build our house in 1968, on 159 Maria Paterno Street, San Juan. That street was named after Lola Mariquita; she had built her summer home there, for the area was breezy, almost a hundred meters above sea level.

Mama was an intelligent investor of our family’s funds, an able manager of her household, and a good cook. She was a devout Catholic and required every one of her children to observe all the practices of the Roman Catholic religion. Every family member attended Sunday Mass. During Holy Week, all children seven years and older were required to attend the rites from Holy Wednesday up to Easter Sunday. Her favorite church for Sunday Mass and the rites of Holy Week was the Jesuits’ St. Ignatius in Intramuros. When all her children were grown she became an officer of the Catholic Women’s League, as treasurer and lastly as its president. She was a contributor to many Church projects.

Mother decided that her eldest child’s first years of schooling should be in a public elementary school. She explained that it was best for me to pursue my first grades in an environment where I would be in the company of children with different backgrounds.

That exposure to other backgrounds was short. It took only a year for me to complete the primary grades. From an early age I had received tutoring via the Spanish caton method of instruction, teaching by rote. Maestra Fermina was an old Spanish-Filipino lady who taught me rudimentary Spanish and how to spell, read, write, and do simple sums. I remember her lessons would begin with my recount in Spanish of what I had for breakfast, followed by her topic for the day. Upon discovery by my elementary school teachers of this training, they accelerated me rapidly through grades one, two, three, and four in just one year. So when Mother transferred me to the De La Salle grade school as a fifth grader, I was only eight years old.

Being perennially the youngest in my class, I was rarely part of my classmates’ social milieu. I was into individual sports. Throughout the grades, I would play by myself. After lunch I would usually look for a game at the handball courts, and if none appeared, bounce a ball off the walls. The game of handball under the noonday sun developed my deep tan, in contrast to the mestizo fairness of many schoolmates. In high school I switched to swimming. From the Taft Avenue campus, our school was just a short walk to the swimming pool of Rizal Memorial Stadiums. I qualified to become a member of the high school varsity swimming team, as a backstroker, and won a medal in competition. I did not join team sports like soccer and basketball, because I was too young to compete with my classmates. When I graduated from high school in April 1941, at fifteen-and-a-half years of age, I was barely out of short pants while my classmates were already attending debuts of their girl friends.

De La Salle high school education was fairly rigorous and gave me a good background for a technical education. We studied plane and solid geometry, trigonometry, and fairly advanced algebra. In science, we were taught chemistry. I still remember Bro. Aloysius, one of several De La Salle brothers from US and Europe, declaring that all the elements had been discovered; there were ninety-two of them then but I am now told that over a hundred elements have been identified. My high school education was adequate in the arts, grammar, and literature. I still remember snatches of Shakespeare, Thomas Gray’s “Elegy Written in a Churchyard,” Sir Walter Scott’s “The Lady of the Lake,” Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s “Paul Revere’s Ride,” Abraham Lincoln’s “Gettysburg Address,” Edwin Markham’s “The Man with the Hoe,” and other works, but science was more appealing to me.

After completing high school in La Salle, I enrolled in Ateneo de Manila’s Industrial Technology course. My interest was actually for manufacturing, but neither La Salle nor Ateneo offered engineering courses. This Ateneo course seemed to offer the closest kind of education. Mother, a devout officer of the Catholic Women’s League, would not at that time have considered enrolling me in non-Catholic Mapua or worse in the liberal campus of University of the Philippines.

My life until then had been lived in comfortable, predictable, peaceful circumstances. In 1925, when I was born, the Philippine population was only 12 million but had climbed to 94 million by 2010. There was enough land for everyone; government functioned and officials attended to people’s needs. There was little poverty. As a student, I remember my baon for school was ten centavos, later upped to twenty, so I could pay the transport fare of ten centavos to go home from Taft Avenue to Quiapo by either bus or tranvia (the Meralco tram). Bus fare for home was required only if my sister Susana was impatient to wait for me to complete my handball game or my swim. Otherwise we would go home together in the family’s 1936 Ford sedan.

My country had been purchased by the United States of America from Spain, our colonial master of 400 years; the occupation was resisted by native arms. However, the USA was a beneficent master compared with Spain. Education and public works greatly improved the situation of Filipinos. Political action by Filipino leaders brought about changes in the country’s political status. From being a colony in 1900, the country was granted Commonwealth status in 1935, preparatory to receiving full independence. The national elections of 1935 resulted in Manuel L. Quezon as Commonwealth president. But the nation’s full independence would not be attained easily. The Filipinos would have to fight for it. Our national life in the 1900s, later referred to as “peacetime” and so ideally pictured in the paintings of Fernando Amorsolo, was soon to change radically. What we later nostalgically referred to as the “Amorsolo period” was about to end.

THE JAPANESE OCCUPATION

My Ateneo studies were short-lived. They ended after six months with the Japanese occupation of Manila in December 1941, after the bombing of Pearl Harbor in Hawaii had begun hostilities. Tertiary educational institutions in the country were closed down. Some were then selectively allowed to open. Ateneo was not—it had too many American Jesuit teachers.

I loved Manila. That December, upon knowing it would be declared an “open city” to preserve it from aerial bombing that would otherwise occur prior to occupation by the Japanese enemy, I spent a whole morning walking through and relishing my city.

I began my walk at Plaza Sta. Cruz. On the sidewalk fronting the tranvias which linked the city, I envisioned them bringing passengers home from downtown to the northern stations. Farther left was Sta. Cruz Bridge, spanning the Pasig River, and beyond it, Plaza Lawton, the central terminus for districts to the south.

From Plaza Sta. Cruz, it was a short walk to Escolta with its upscale shops and two movie houses, Lyric and Capitol. At the other end of Escolta is Jones Bridge, and the finance area, beginning with National City Bank of New York, where my family deposited its savings. Then I walked to Rosario Street, where the Chinese money people held office, then back down Escolta and past the Sta. Cruz Church to the parking area for the panciterias fronting Sta. Cruz Church, or the lone movie house, moving on through the narrow street to enter Avenida Rizal, its many shops, and four movie houses. Traversing Rizal Avenue, I headed back to Carriedo Street, Quiapo Church, and home via R. Hidalgo and the tram stop.

Being a college student enrolled in the Reserve Officers Training Corps (ROTC), I was called to military service and spent over two weeks in barracks and guard duty at the Ateneo campus. However, when the time came for ROTC members to be deployed for battle in Bataan, I was sent home, being underage, having just turned sixteen. Moreover, there was a shortage of rifles for issue. Upon my return home to Mendoza Street, Quia...