![]()

Part of the appeal of early silent cinema was that the audience didn’t need to be literate or even be able to speak English. They spoke the universal language of visual images, ‘the Esperanto of the Eye’, as one writer called it.

I

HOLLYWOOD

FOUNDING FATHERS

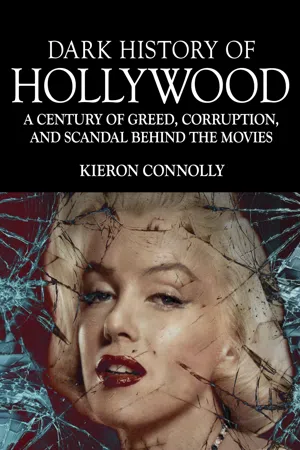

In 1908, America’s cultural life, including its film-making, was led from New York, and France had the world’s largest film industry. So how was it that by 1919 Hollywood had become not only the centre of film-making in the United States but also the largest force for movies around the world? As well as hard work and good luck, it’s a story that involves bootlegging, theft, piracy, cartels and violence.

‘Cinema has no commercial value. At most, it’ll last a year.’

Cinema wasn’t conceived in Hollywood, but some would argue that it was born in America. In 1896, the cinématographe, invented by Antoine Lumière and his sons Louis and Auguste, was presented in New York. While earlier inventions had been more like slot machines where a single viewer looked through a peep hole, the cinématographe was the first projector to throw light and shadows on a wall and offer moving images to a mass audience. Quickly the cinématographe, which gives us the word ‘cinema’, proved a success around the world – so much so that within a year it had been studied and improved upon by other moving-picture inventors.

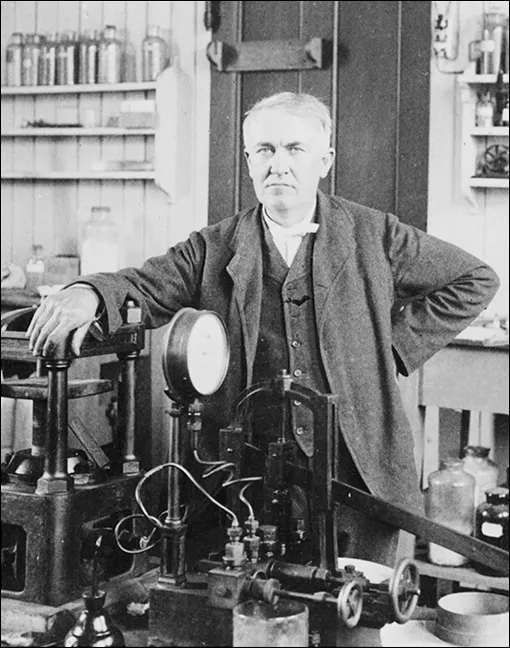

But, as the movie business now knows well, where there’s a hit, there’s a writ. No sooner had the Lumières demonstrated their invention than Thomas Edison, inventor of the light bulb, the phonograph and the ticker-tape machine, as well as being a busy litigator, stepped in. Claiming that he’d created a device for viewing moving pictures five years earlier, he went to court, alleging that all other machines were infringing his patent – this despite the more recent inventions being far more sophisticated and the fact that Edison’s machine itself owed a great deal to the earlier work of Étienne Jules Marey. The battle for who owned cinema had begun, and it wasn’t a battle fought only in the courts – Edison’s lawsuit against American Mutoscope (later the Biograph Company) lasted for ten years and even lead to street fights. But while the lawsuits were making their way through the legal process, cameras could be rented, bought or stolen – the bootlegging of equipment and even finished films being common.

SEATS FOR THE FUNERAL

WHEN SAM, HARRY and Albert Warner – the three elder Warner Brothers – opened their first nickelodeon in Pennsylvania in 1905, they used chairs from the funeral parlour next door. If they had a very popular film showing, a funeral service would have to be postponed while they borrowed the chairs. And if the undertaker had a large service, they’d delay the start of their film until the chairs were available.

Harry Warner (centre), with Albert (right) and fourth brother Jack (left) in 1965.

While the lawsuits were making their way through the legal process, cameras could be rented, bought or stolen …

With films proving relatively inexpensive to make, offering returns that could be very high, one early commentator said: ‘All you needed was fifty dollars, a broad and a camera.’ With that, a short, silent vaudeville act could be put on film.

As movies were at first basically a fairground attraction, another observer correctly described the people involved in them as a ‘collection of former carnival men, ex-saloon keepers, medicine men, concessionaires of circus side shows, photographers and peddlers’. Cinema was cheap entertainment aimed not at the well-off but the urban poor, with the result that initially cultured and professional financiers missed out.

Others, however, saw the possibilities. And as cinema became more successful, more permanent homes for screening films sprang up in disused shops and theatres in America’s slum districts. These venues were called ‘nickelodeons’, a clever mix of the cheap and the grand: the cost of admission was a nickel (5 cents), while ‘odeon’ was Ancient Greek for a building where musical performances were held.

Nickel Delirium

The beauty of silent films was that they could be enjoyed by new immigrants without fluent English, the way theatre and even vaudeville could not. And almost everyone was welcome at a nickelodeon. Unlike restaurants, vaudeville or social clubs, no one was barred from a nickelodeon on account of gender or religion, or, with some exceptions, race (although in many US states nickelodeons were segregated). Offering everyone the chance to sit privately but in public, a woman could go to a nickelodeon without an escort and without being the focus of unwanted attention. The most popular genres were comedies and thrillers, and few films lasted more than 25 minutes.

Charles Pathé began in business with a phonograph stall at French fairgrounds, before turning his attention to the mass production of movies. ‘I didn’t invent cinema,’ he said, ‘but I did industrialize it.’

Offering everyone the chance to sit privately but in public, a woman could go to a nickelodeon without an escort.

It’s estimated that by 1907 there were more than 4000 nickelodeons across America, each of them offering 12 shows a day, with 200,000 people a day going to the movies in New York alone. The number doubled on Sundays.

But although nickelodeons were quickly booming across America, it was the French company Pathé that was making the most films. Completing one short film every day by 1908, Pathé was producing silent fantasies, biblical stories and melodramas, and soon opened offices in Bombay, Singapore and Melbourne to supervise their distribution. America wasn’t even the second largest film-producing country – Denmark was, with Copenhagen-based Nordisk large enough to employ 2000 people in an industry that was barely a few years old.

But when Charles Pathé complained that Edison was pirating copies of his films for US release, Edison responded by issuing Pathé with a writ. Trying to hold on to what he perceived as his intellectual copyright over cinema, Edison issued lawsuits alleging that film companies and cinemas not using his equipment were infringing his patent on cameras and projectors. And when legal channels didn’t work swiftly enough, Edison turned heavy, hiring private detectives and thugs to harass his competitors as they were actually filming. Although some rivals quickly set up decoy film crews to occupy the detectives, while the genuine crew worked undisturbed elsewhere, eventually, through channels legal or otherwise, Edison managed to hound many companies out of business.

… when legal channels didn’t work swiftly enough, Edison turned heavy, hiring private detectives and thugs to harass his competitors …

The Arrival of the Moguls

It wasn’t long before the success of cinema began to attract a new generation of entrepreneurs. They weren’t well educated and they weren’t scientists or inventors, like Edison or the Lumières, but they were determined and had a keen eye on the market. They were Jewish immigrants from Europe, who were seeking a better life in North America: Samuel Goldwyn was from Warsaw, Adolph Zukor (one of the founders of Paramount Pictures) and William Fox (whose company merged to form 20th Century Fox) were Hungarian, while Carl Laemmle (of Universal Pictures) was from Germany. All moved to the US as teenagers. Louis B. Mayer (later of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer), who was from Minsk, Belarus, moved to the US as a toddler and three of the four Warner brothers moved from Poland as children. All of them worked their way up in other forms of business: Goldwyn became a master glove salesman, Zukor was in furs, Fox was in the garment trade, Mayer in scrap metal and the Warners struggled through various modest ventures, including a bicycle shop. In Hollywood style, their lives would become rags-to-riches stories. With most of them having done well in their respective businesses, they would succeed in resisting Edison’s attempts to monopolize the new medium.

Risking losing control of the film business to these new, independent nickelodeon entrepreneurs, Edison and his main competitors at American Mutoscope and Biograph Company (AM&B), agreed in 1908 to settle their differences and create a cartel to keep the upstarts out. In this they tried to monopolize the cameras and projectors that made film-making possible. Titled The Motion Picture Patents Company (MPPC), competitors quickly referred to the cartel as ‘The Trust’.

By limiting the number of companies allowed to use its film stock, cameras and projectors, the Trust barred many US and all but two overseas producing companies, one being Pathé. Before the Trust’s measures were put into action, foreign films had made up more than two-thirds of the total number of films released in America, but within a year that figure had halved. The European film industry, which had come to rely on America as its largest export market, was never as powerful again. By limiting foreign imports, the Trust had muscled its way to the top of American cinema.

Thomas Edison tried to dominate movies by controlling the use of his inventions – cameras, projectors and film stock. The more commercially minded understood that the money in cinema was actually in making and distributing films.

Carl Laemmle, the founder of Universal, with his children Rosabelle and Carl Jr Laemmle, whose named is pronounced ‘lemlee’, was known for employing his relatives – as Ogden Nash rhymed: ‘Uncle Carl Laemmle, has a very large faemmle.’

At a time when women in most US states didn’t even have the vote, Pickford was able to choose her co-stars and directors.

Cinema’s First Stars

Universal’s Carl Laemmle only managed to abide by the Trust’s terms for three months before he rebelled, putting an advertisement in the trade press: ‘I Have Quit The Patents Company … No More Licenses! No More Heartbreaks!’ To meet the demand of supplying cinemas with non-Trust films, however, Laemmle realized he’d have to start making movies himself. Renting space in New York, he launched his own studio and set about looking for talent to put in front of the camera.

Many actors and actresses were already tied into long-term contracts with the Trust companies, which deliberately didn’t name them, rightly suspecting that if they did, they’d become the attraction and would begin demanding higher fees. For this reason, Biograph’s Florence Lawrence was known only as ‘the Biograph Girl’, while Mary Pickford was ‘The Girl with the Curls’.

At one point, Laemmle even moved his company to Cuba, but still found mysterious ‘tourists’ busying themselves photographing the company’s equipment …

When Laemmle managed to poach Lawrence and Pickford from Biograph in 1909 and they began working under their usual stage names, Pickford’s weekly salary climbed from $175 to $10,000, with a yearly bonus of $300,000. At a time when women in most US states didn’t even have the vote, Pickford was able to choose her co-stars and directors. Movie acting, for a select few, rapidly became the highest paid profession in the world.

Not that the Trust had given up trying to police the use of cameras. At one point, Laemmle ev...