![]()

Aelbert Bouts’ fifteenth-century altarpiece suggests the brutal violence behind a faith which was founded in the sufferings of its Saviour. Christ’s disciples, in the early centuries, knew that their own fate was unpredictable; that they themselves might easily come to grisly ends.

I

CATHOLIC CHURCH

VIA DOLOROSA:

EARLY PERSECUTIONS

‘I am the way, the truth and the life,’ Jesus promised his disciples – but the cruelty of his Passion was to bring them a clear warning: the Christian faithful could expect to endure great suffering and loss.

‘Take this cup of suffering from me.’

– MARK, 14: 26

The rich young man instructed to give away all his possessions to the poor; the outraged citizens told to think of their own sins before they attacked the adulteress; the victim of violence ordered to ‘turn the other cheek’ … Christ’s first followers were left in little doubt that, although their faith would ultimately bring them to Everlasting Life, it would cost them – perhaps very considerably – in the here and now. Indeed, whatever joy it brought, the road to Salvation was inevitably going to lead them through deep and difficult vales of darkness and death. The story of the early Church was to be no different. By 312, Christianity would be basking in the backing of the state, the official religion of the Roman world. First, though, there were terrible persecutions to be endured.

The First Martyrs

The radiance of the Resurrection fading, Christ’s Ascension quickly coming to seem more like an abandonment, the darkness wasn’t long in falling for the followers of Christ. The first known martyrdom – the stoning to death of St Stephen in Jerusalem around AD 35 – was witnessed by the future St Paul. Then still known as Saul, a young man from Tarsus in the province of Cilicia (southern Turkey), he was as proud of his Roman citizenship as of his Jewish background. Stephen’s stand appeared an affront to both. So much so that, far from objecting to what amounted to a religious lynching, Saul stood by and minded the cloaks of the killers as they hurled their stones at Stephen. Later, of course, his attitudes were to be transformed by the extraordinary experience he underwent on the Road to Damascus. Now named Paul, he became co-founder with St Peter of what we now know as the creed of Christianity. And while Peter may have been Christ’s anointed Pope, Paul was arguably more important in building the Catholic Church: it was under his influence that it transcended its origins as a Jewish sect.

Nero fastened the guilt and inflicted the most exquisite tortures on a class hated for their abominations, called Christians by the populace …

Both St Peter and St Paul were to die in Rome, the centre of the civilized world in the first century AD. Both were martyred, according to the Christian tradition. While St Paul was beheaded, St Peter was crucified just as his mentor had been – but upside-down, it’s said, at his own request. His death by crucifixion might have been ordered in sneering allusion to his Saviour’s, but to St Peter it was an honour of which he was unworthy. Hence, the story has it, his desire to be executed the wrong way up. A great basilica was later raised up above his grave.

Fire and Sword

We view these events today as the beginnings of a great religious, historical and cultural tradition. For the Roman Empire, though, they were very much a minor, local thing. Most Romans were barely conscious of Christianity’s existence. If they were, they saw it as the obscure offshoot of an obscure Middle-Eastern sect – one of innumerable little cults to be found in the most cosmopolitan city the world had ever seen. That it came to widespread attention at all was down to the opportunism of an Emperor in need of a convenient scapegoat for his political difficulties.

A wild paranoiac in the most powerful position in the world, Nero was a public menace, nothing less. His reign, which lasted from AD 54 till his deposition by a desperate Senate 14 years later, was characterized by madness, murder and repression on a monstrous scale. Further disaster struck when fire ravaged Rome in AD 64. The impact of the conflagration was immense. According to the historian Tacitus, writing just a few years later:

‘Rome, indeed, is divided into fourteen districts, four of which remained uninjured, three were levelled to the ground, while in the other seven were left only a few shattered, half-burnt relics of houses.’

Nero wasn’t just the man in charge, it seems: some suggested that he had contrived the disaster deliberately, wishing to clear the site for a spectacular new palace he had in mind. As the Roman writer Suetonius says:

‘… pretending to be disgusted with the old buildings, and the streets, he set the city on fire so openly, that many of consular rank caught his own household servants on their property with tow, and torches in their hands, but durst not meddle with them. There being near his Golden House some granaries, the site of which he exceedingly coveted, they were battered as if with machines of war, and set on fire, the walls being built of stone.’

In need of someone else to blame, writes Tacitus,

‘Nero fastened the guilt and inflicted the most exquisite tortures on a class hated for their abominations, called Christians by the populace … Mockery of every sort was added to their deaths. Covered with the skins of beasts, they were torn by dogs and perished, or were nailed to crosses, or were doomed to the flames and burnt, to serve as a nightly illumination, when daylight had expired.’

This seems to have been the context in which, along with so many others, St Peter was arrested and put to death – just another minor move in the wider game of Roman politics.

Ups and Downs

The sense that it was a religion tried in the fire was to be central to the developing consciousness of Christianity, but it’s clear that there was ‘nothing personal’ as far as Roman Emperors were concerned. Nero’s clampdown, horrifying as it may have been, was nakedly opportunistic. Time and time again through the second and third centuries, we find Christianity being attacked – or tolerated – with the same disregard. In between dreadful persecutions in the reigns of the Emperors Domitian, Trajan, Septimius Severus and Decius, came lengthy periods of easy-going acceptance: the mood typically turned ugly when economic times were hard.

St Stephen’s ugly death – he was stoned by an angry mob (the young Saul – later St Paul – was a bystander) – takes on an extraordinary beauty in Pieter Paul Rubens’ representation (c.1617). Its ability to transmute mortal pain into something more blessed was part of Christianity’s appeal.

St Paul was proud of being both a Jew and a Roman citizen: it is largely thanks to him that the Catholic Church was based in Rome. It was to his citizenship that he owed his good fortune in being beheaded – death by crucifixion was reserved for non-Romans.

St Peter, it is said, on hearing that he was to be crucified, begged that he be hung up upside-down so as not to seem sacrilegiously to imitate his saviour. He was killed in Rome, and St Peter’s Basilica built over his tomb.

Many priests and bishops were martyred in the reign of Valerian (253–60), including St Lawrence, reputedly burned on an iron grill. (‘Turn me over, I’m done on this side…’, he told his tormentors, tradition has it.) A few years later St Sebastian was forced to face a squad of archers. Such deaths were to take their places in a tradition of martyrology that was to be essential to the early Church’s identity – like that of St Catherine of Alexandria, sentenced to have her body broken on a wagon wheel.

The Great Persecution

The Emperor Diocletian was tolerant by nature. By the end of the third century, however, the Empire was coming under strain. Financial mismanagement had resulted in economic difficulties in what was already so vast and unwieldy an Empire as to be effectively ungovernable – Diocletian had felt compelled to appoint four sub-emperors to reign across the regions on his behalf. It made sense at the same time to underline the ‘Romanness’ of the Roman world by reaffirming its cultural values – none of course loomed larger than the old religion and its rituals.

GETTING NERO’S NUMBER

DRIVEN UNDERGROUND BY Nero’s persecution, the Christians had to communicate with one another secretly. Given that most shared Jewish backgrounds, they were familiar with the traditional numerology known as gematria. This ancient mystic system associated specific properties to different numbers in relation to the letters of the Hebrew alphabet. Gematria was a vast and erudite subject in itself: you could spend a lifetime exploring its infinite subtleties. At its most basic level it offered a ready-made code for initiates. For the name Nero, the figures came to 666: notoriously, the ‘Number of the Beast’ in the Book of Revelation. For the early Christians, the Emperor was indeed the ‘Antichrist’.

In 303, therefore, the Emperor issued his ‘Edict Against the Christians’. As the contemporary Christian scholar Eusebius put it, officials were ‘to tear down the churches to their foundations and destroy the sacred scriptures by fire’. Those ‘in honourable stations’ were to be ‘degraded’ (reduced to slavery, in other words) if they refused to abjure their faith. Thus began the ‘Great Persecution’. Contemporary sources claim that 10,000 martyrs were crucified side by side on the first day. And while this is surely an exaggeration, there’s little doubt that many thousands must have died in a reign of religious terror that was to continue unabated for the next eight years.

‘A Certain Religion of Lust’

These were dark times for the Church indeed. But there was no shortage of contemporary commentators ready to suggest that the Christians had brought their sufferings on themselves with dark deeds of their own.

It’s a tribute to Jesus’ radicalism that his central tenets seemed so hard for so many to take on board: ‘They love one another almost before they know one another’, one scribe complained.

Diocletian was responsible for the deaths of thousands in the ‘Great Persecution’ he launched in 303. Christians were tolerated for decades on end, but could never feel secure – in times of economic hardship they made the ideal scapegoats for all the Empire’s ills.

Understandably, perhaps, Pagan contemporaries were cynical about the whole ‘Love thy neighbour’ message and found it hard to recognize the distinction being made between affectionate goodwill and sex. ‘There is mingled among them a certain religion of lust’, one said. ‘They call one another promiscuously brothers and sisters’. The word ‘promiscuously’ here, of course, isn’t used in a sexual sense, but it’s easy to see how suspicious all this ‘love’ and siblinghood must have seemed. Suffice it to say that the suspicion of incest was never far away.

Feared and distrusted minority groups are just about invariably accused of sexual deviance, of course: ‘Some say that they worship the genitals of their pontiff and priest’, one critic said. The same source revealed: ‘I hear that they adore the head of an ass, that basest of creatures, consecrated by I know not what silly persuasion.’ Such reports were – it goes without saying – entirely wild.

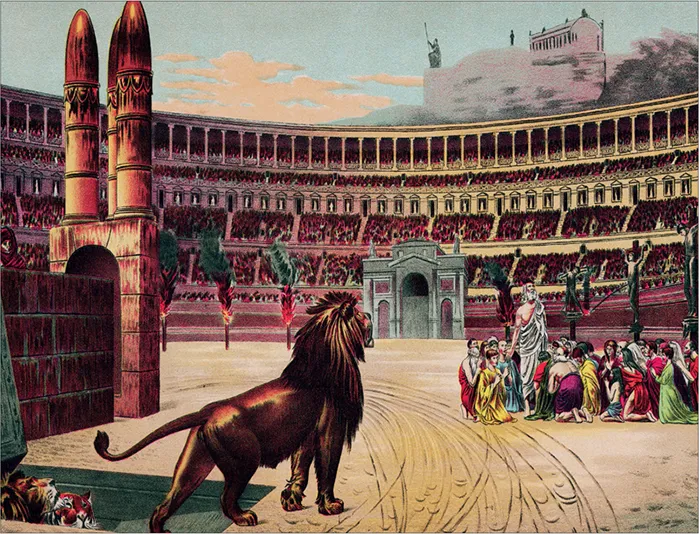

‘The Christian Martyr’s Last Prayer’ was famously imagined by French artist Jean-Léon Gérôme in 1883. There’s surprisingly little evidence for the tradition that Christians were ‘thrown to the lions’ in ancient Rome, but no doubt that in times of persecution many suffered torture and cruel death.

I hear that they adore the head of an ass, that basest of creatures, consecrated by I know not what silly persuasion.

Worse than these absu...