![]()

Everything began with God (above). But, as the alpha and omega of his holy book remind us (left), he defines our end as well. Here an angel exhibits the treasures of the earth, holding up an astrolabe (an antique model of the heavens).

I

THE BIBLE

GENESIS: FALL, FRATRICIDE AND FLOOD

‘Let there be light,’ came the famous fiat, but hardly was God’s creation complete than human disobedience plunged everything back into darkness and sin.

——♦——

‘Darkness was upon the face of the deep.’ GENESIS 1, 2.

First things first. ‘In the beginning’, the Book of Genesis tells us, ‘God created the heaven and the earth.’ The idea of higher and lower states is central from the start. The difference is all-important: this is to be a universe articulated in the first instance by its divisions and its distinctions (‘And God divided the light from the darkness’, 1, 4), and only secondarily by its definitions of what things are (‘And God called the light Day, and the darkness he called Night’, 1, 5).

Order is to be important too. No time is lost in establishing the essential rhythms and routines of earthly existence (‘And the evening and the morning were the first day’, 1, 5).

‘And God saw that it was good,’ we’re told (1, 13), and yet what has clearly been a codification, a laying-down of laws, inevitably brings with it at least an implicit thought of rule-breaking, of disorder. The goodness of God’s creation has been summed up in his command that there should be ‘light’ (1, 3); but every day, we’ve already been told, contains its darkness – ‘night’.

Man and Woman

The stars; the sun and moon; ‘the moving creature that hath life, and fowl that may fly above the earth’; the ‘great whales’, ‘fish’ and ‘cattle’ and the ‘creeping thing’. Having brought all these beasts into being, God decides (1, 26) to ‘make man in our image, after our likeness’, resolved to give him ‘dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over the cattle’. That man is made ‘in the image of God’ only underlines his special status among the wonders of creation: ‘Behold’, says God:

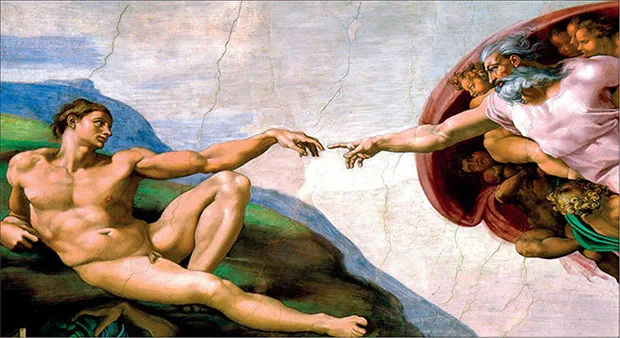

Man, said his creator, was made ‘in our image, after our likeness’. The Renaissance liked to take him at his word. Michelangelo’s famous scene from the Sistine Chapel (c. 1511) makes the very most of the majestic beauty of the human form.

I have given you every herb bearing seed, which is upon the face of all the earth, and every tree, in the which is the fruit of a tree yielding seed; to you it shall be for meat.

So Good He Made them Twice

‘So God created man in his own image,’ says the Book of Genesis (1, 27): ‘in the image of God he created him’. Does the male pronoun encompass the female too? It seems to – at least to begin with, verse 27 continuing immediately on to elaborate: ‘male and female created he them’.

That appears to be the end of it. God’s creation is complete, the whole thing being rounded off with the now customary note that God saw that it was ‘good’. Just a few lines later, though, in Chapter 2, verse 7, we find ourselves starting over: ‘the Lord God formed man of the dust of the ground, and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life, and man became a living soul.’

And still no sign of Eve. Adam is alone when (2, 8) he’s given his own ‘Garden eastward in Eden’ as a home. Only afterwards does God consider that ‘It is not good that the man should be alone’ and resolves to make ‘an help meet’ for him. Even then, there’s the business of ‘every beast of the field, and every fowl of the air’ being brought to Adam, so that the first man could allot them all their names. Only when that day’s work is done does God cause a ‘deep sleep’ to fall upon him, during which ‘he took one of his ribs, and closed up the flesh instead thereof’. It’s Adam who names this animal too: ‘This is now bone of my bones, and flesh of my flesh: she shall be called Woman, because she was taken out of man,’ he says.

Winds blow; the sun and moon both shine; fish, fowl, cattle and other creatures throng around as God completes his labours with the ‘birth’ of woman (2, 21). Eve emerges fully-formed from the side of her (miraculously sleeping) husband.

GOLDEN AGE

THE IDEA THAT the first men and women lived untroubled lives in a land of endless ease and pleasure was by no means unusual among ancient cultures. For the Greek poet Hesiod, in the seventh century BCE, he said that our first forebears were lucky enough to live during a ‘Golden Age’:

They lived like gods and felt no sorrow. They did not toil, nor did they grow old, but remained strong in hand and foot. They ate and drank freely, with no sufferings to dampen the mood. Even when they died, they did so easily, as if simply falling asleep. All good things came to them without asking, for the fertile earth brought forth its bounty spontaneously and without limit: they could just sit back and enjoy their ease and comfort, beloved of the gods and rich in livestock.

Hindu tradition talks of the Krita Yuga, a First and Perfect Age in which all were equal, with no divisions of wealth or caste; no death, disease nor even ageing; nor any need to labour in a world that gave freely of its plenty. In these traditions the ‘Fall’ of Man is more a series of stages of decline: the Greek Golden Age is succeeded by epochs of Silver and Bronze – and a wretched present one of Iron. But the Babylonian Epic of Gilgamesh has pretty much the whole story as we see it in Genesis, including a mud-made man being tempted by a woman – and even a seductive snake.

However problematic its account of her creation, the Bible is clear on the perfection of woman as counterpart and as companion to her husband, ‘the bone of my bones, and flesh of my flesh’ in Adam’s words (2, 23).

Already, by its second chapter, then, the Genesis account is proving problematic. The inconsistency is easily enough explained. So long, that is, as the reader is willing to accept the modern scholarly consensus that this narrative represents a composite of several different early sources – a sometimes clumsy synthesis, if truth be told. There’s no great difficulty or ‘darkness’ here, then, for most of us, but for those who’d hope to find in the Bible a literal, factual account of the world’s origins, and our own, the implicit warning could hardly be more clear.

DEVIL WOMAN

THE EARLIEST JEWISH readers don’t seem to have been much troubled by the discrepancies between Genesis’ two accounts of the creation of man – and, more to the point – of womankind. Only later did it start causing concern. The difficulty was easily resolved, however: seizing upon the fact that the ‘female’ of Chapter 1 is never named, writers came up with the idea of an earlier woman who had to be dispensed with as she proved unworthy.

Hence the story of Lilith, Adam’s first wife – a monster of insubordination and sexual rapacity; the antithesis of all approved forms of femininity. It’s no surprise to find her mythical antecedents extending back into Mesopotamian demonology. No surprise because her first actual mention in the Bible comes in the Book of Isaiah, thought to have been written at least in part during the Babylonian Captivity; but also because her devilish nature suggests some such origins. Lilith didn’t really come into her own till post-Biblical times, in the Balmud Bavli (mid-First Millennium CE) and the medieval Alphabet of Ben Sira and other mystic writings in which she becomes the terrifying embodiment of femininity at its most seductive and its most threatening. Sexually insatiable, irresistibly appealing, she was Freud’s vagina dentata incarnate, her irresistible body the beguiling way to hell. In one thirteenth-century account, she abandons Adam for Samael, Archangel of Death and Destruction, her affinities and her loyalties all too clear.

Modern feminist scholars haven’t of course been shy of registering their unease at the importance attributed to Eve, a woman, in the ‘Fall of Man’. The Lilith legend doubles down on this tradition, removing all question of ‘mere’ weakness or impressionability, replacing sexist condescension with a more aggressive misogyny.

The prevalence of female spirits in Mesopotamian tradition gave the Lilith legend a doubly sinister status. This devil-woman didn’t just stand for the frailties generally associated with womanhood, but with all the evils associated with paganism by Jewish and Christian scholars.

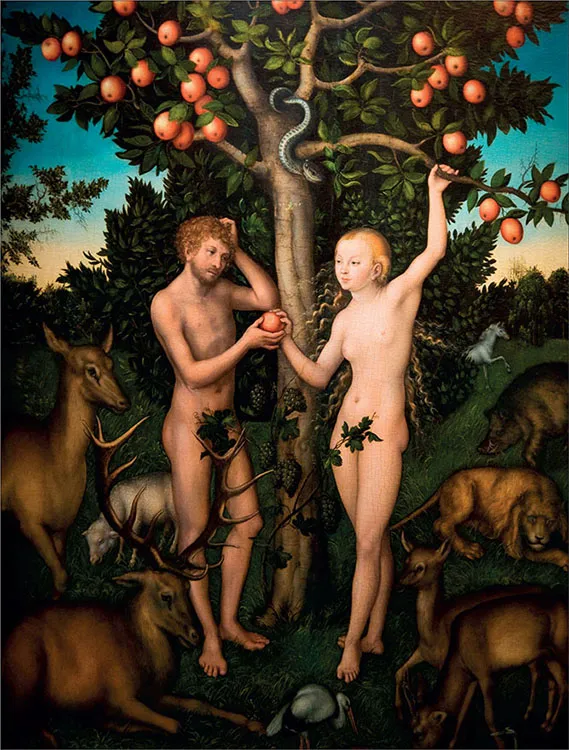

Cherchez la femme … The serpent stays in the background here: Eve stares insouciantly off into space as an ingenuous-and bewildered-looking Adam takes the apple in Lucas Cranach the Elder’s classic depiction of the Fall (1526).

‘But of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, thou shalt not eat of it’.

GENESIS 2,17

Eve’s Temptation

‘Of every tree of the garden thou mayest freely eat,’ God tells Adam (2, 17): ‘But of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, thou shalt not eat of it: for in the day that thou eatest thereof thou shalt surely die.’ But the serpent – ‘more subtil’, according to Genesis, ‘than any beast of the field which the Lord God had made’ – sets out to persuade Eve that this fearful warning is just bluster on the creator’s part:

Ye shall not surely die: For God doth know that in the day ye eat thereof, then your eyes shall be opened, and ye shall be as gods, knowing good and evil.

Eve, then, takes the fruit and eats it; and she gives it to her husband and he eats it too, ‘And the eyes of them both were opened, and they knew that they were naked; and they sewed fig leaves together, and made themselves aprons.’ This new-found bashfulness is what betrays them: their efforts to conceal themselves from God arouse his ire. ‘Who told thee that thou wast naked?’ he demands. Damning the serpent to crawl upon his belly and eat dust for all his days, he curses Eve to a life of suffering and subjection:

Sent out of the sunshine of the earthly paradise into a dark, drear wilderness, Adam and Eve can now anticipate lives of suffering and toil. Ultimately, however, this disgrace was to open the way to a more meaningful paradise in heaven.

I will greatly multiply thy sorrow and thy conception; in sorrow thou shalt bring forth children; and thy desire shall be to thy husband, and he shall ...