![]()

I

THE FIRST CAESARS

In 27 B.C.E., Octavian took the name Augustus (‘splendid’) and the title Imperator. Single-handedly, he had created the office of Emperor. But barely had he done so than it was being brought into disrepute – first by his daughter, then by his successor.

The Empire’s first official head of state, Augustus made himself the face of Rome: his profile was displayed upon the Empire’s coinage (pictured).

The official record shows Augustus’ reign as one of prosperity and success, and that is true enough, as far as it goes. It helped that the first Emperor held sway for so long. For 41 years in all, his authority was unquestioned. So, too, for that matter, was Rome’s. The Pax Romana (‘Roman Peace’) now established in the Empire was to continue from Augustus’ reign for nearly another 200 years. After so many decades of civil strife, a return to order came as a huge relief for the people living under Roman authority. That Augustus, in his days as Octavian, had himself caused so much of the trouble was mostly forgotten. What mattered was that he was now presiding over peace.

And he had made Rome great. Who could doubt that when, year by year, they saw yet more grandiose public buildings going up around the capital? ‘I found a city of brick,’ Augustus was to say, ‘and left it one of marble.’ That may have been an exaggeration, but he did have a point. Contrast that public grandeur with the simplicity of Augustus’ private life. Augustus was ostentatiously unassuming, and he had a busy propaganda machine making sure that everyone knew just how modestly he lived.

His beloved wife, Livia Drusilla, became the iconic Roman wife: devoted, loyal, tough and a little bit severe. Livia Augusta, as she was known after her husband’s promotion to the rank of Emperor, made sure that she presented herself as her husband’s helpmeet. She was beautiful, but worked hard not to flaunt it. Her straight, simple gown announced a no-frills personality. Her hair was neat, but styled in a way that showed her discipline and restraint. She let it to be known that she spent her time weaving and performing other womanly – but never frivolously ‘feminine’ – tasks. Livia Augusta had no greater ambition than to uphold the dignity of Rome.

She stood by her man with most admirable selflessness, even to the point, it is said, of bringing him virgins to deflower. Dignity was what mattered. As long as adultery didn’t jeopardize the reputation of the house it didn’t count as adultery at all. Slave girls did not count either, so there was really no reason for Livia to worry about what her husband got up to, as long as her prestige as ‘Livia Augusta’ remained secure.

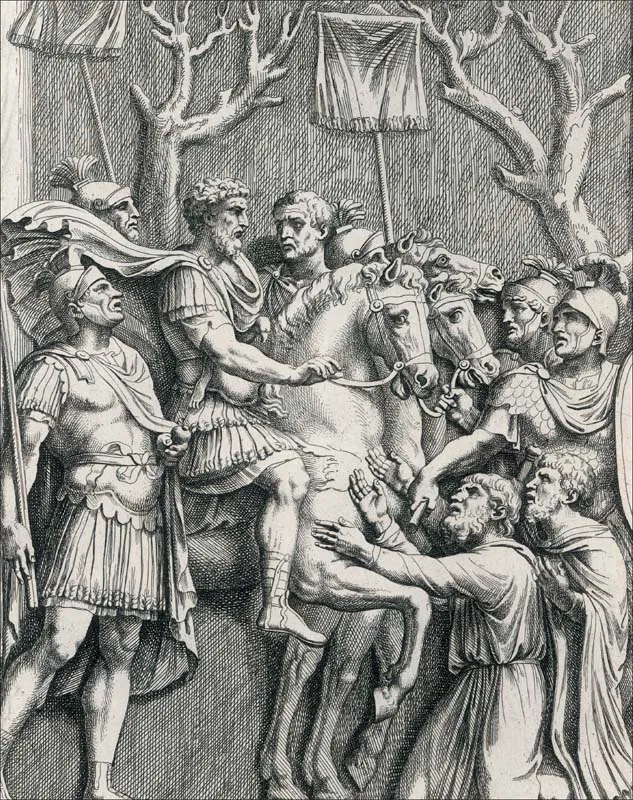

The title ‘Imperator’ was a military one, meaning ‘man who gives the orders’, or ‘general’. The Emperor’s primary role was as commander-in-chief. Years of civil war had equipped Augustus well; here he makes his victorious entry into Syria, around 27 B.C.E.

Augustus ordered spectacular building projects, not only in Rome but across the Empire as well. This awe-inspiring outdoor theatre in Orange, France, and the regular public shows that were presented here, underlined the power and prestige – and the generosity – of the Emperor who endowed them.

Livia’s admirable matter-of-factness was underlined when, one day, walking through the palace, she came across a group of men who were naked after some exercise. By rights they should have been summarily executed, having compromised the purity of the Empress’s presence, but Livia gave the order that they should be spared. The sight of a naked man, she said, was no more disconcerting for a woman who was truly chaste than the sight of a marble statue would be.

FAMILY VALUES

Augustus saw no inconsistency (no Roman would have done) between his little liaisons with concubines and his aggressive public campaign for ‘family values’. He executed one freedman whom he had long regarded as a personal friend because of his adulterous relationships with aristocratic wives. It was the offence to Rome’s noble households, and therefore to the social status quo, that Augustus objected to in such relationships. He was unconcerned about any moral issues or the emotional hurt that such adultery might cause.

Augustus saw no inconsistency between his little liaisons with concubines and his aggressive public campaign for ‘family values’.

He felt so strongly about the potential upheaval to society that adultery could cause that Augusts brought in legislation outlawing it: a husband who caught his wife with a lover was legally entitled to kill them both. The same right existed for a father who caught his daughter in adultery. A husband who learned of his wife’s infidelity had not just a right but a duty to divorce her within 60 days; she would be banished, and face financial penalties. Women were forbidden to appear in a wide range of public places, and there was a duty in both sexes to marry. Men under 60 and women under 50 were obliged to wed if they were single: if they failed to do so they lost the right to inherit property.

AN UNDUTIFUL DAUGHTER

The imperial couple may have presented a powerfully united front to Rome and the world, but behind the scenes all was not quite as calm as it appeared. Livia was the Emperor’s third wife. While he had returned his first bride, Clodia, to her father ‘untouched’, already seeing more dynastically advantageous possibilities in a marriage to Scribonia, the daughter of an ally, that second marriage had been a disappointment, to put it mildly. By all accounts, Octavian had been worn out by Scribonia’s nagging: her one redeeming act, he claimed, was to have borne him a baby daughter. That done, he divorced Scribonia on the very same day: she rose from her bed having given birth to find herself a single woman.

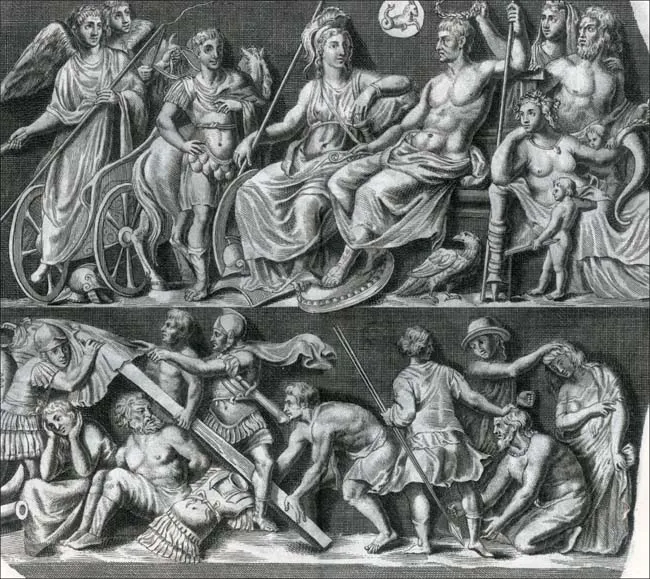

Seated in his rightful place among the gods – and attracting respectful glances, even in this company – Augustus can leave the work of conquest to his victorious soldiers, shown below. After his death, Augustus was quite genuinely worshipped as a deity, as was his Empress, Livia Augusta.

Idlers drink and gossip outside Agrippa’s house in this painting by Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema. One leans back casually against the plinth on which the Emperor’s statue stands with its right arm raised in an ironic gesture of command. Augustus’ authority was as badly undermined by his daughter’s dissolute lifestyle as his friend Agrippa’s was from being her husband.

Octavian’s gratitude for his daughter Julia did not survive long past her infancy. Brought up by himself and Livia, she was a rebel. Her first marriage, to her cousin Marcellus, might have worked out if he had not been taken ill and died on a military campaign in Spain. Her second, to Agrippa, an ally of Augustus, 25 years her senior, was disastrous. It did yield two grandsons for the Emperor, Gaius Caesar and Lucius Caesar, whom a delighted Augustus adopted and groomed as his successors. Julia didn’t get anything she wanted out of the marriage, however, and soon began a long-term love affair with one Sempronius Gracchus. And he, the gossips maintained, was the first of many.

In 12 B.C.E., Agrippa died. Augustus promptly arranged another marriage for his daughter, this time to his stepson Tiberius. He had been born to Livia in a previous marriage but, like Gaius and Lucius Caesar, was taken up by the Emperor as his own. This marriage, too, was a mismatch from the start, but Julia’s sins were now doubly damaging because she was not only bringing disrepute upon the ruling family with her outrageous adulteries, but was also doing so at the expense of a husband who was himself a member of that family. And she was doing it openly. Rome was abuzz with gossip about all her affairs and her very public nightly drinking parties in the Forum. This was at a time when her father had introduced laws demanding that women should barely be seen in public, even in the daytime. That a woman should be out drinking with men at night was beyond the pale. In the circumstances, it is difficult to avoid the suspicion that Julia was driven by a determination to humiliate her father, the Emperor, as deeply as she could.

‘I found a city of brick, and left it one of marble.’ Augustus’ boast was no idle one; his redevelopment of the Forum was especially impressive. The Emperor made a point of the contrast between his ostentatiously simple private life and the splendour of his public building schemes.

Every time he saw Agrippina, Tiberius recalled his humiliation at her mother’s hands; their relationship only worsened as time went by. Rubens presents them here in profile – they were never to see eye to eye.

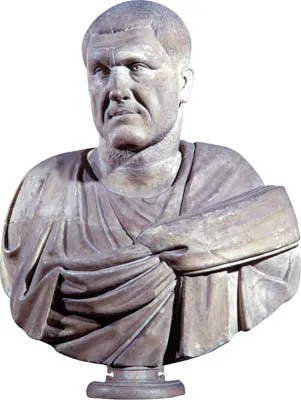

His bust exudes authority, but increasingly Augustus was being exposed to ridicule as a result of his daughter’s drunken escapades and illicit sexual liaisons. In the end, the Emperor had to show that he was master in his own house by making a public example of Julia and her lovers.

Augustus certainly had no alternative but to act. By rights, he should have had his daughter executed. He did have the most open and unabashed of her lovers, Iullus Antonius, forced into committing suicide. Sempronius Gracchus got away with exile, as did several other men. Julia, too was exiled, sent to the offshore island of Pandateria (Ventotene) with Scribonia, her mother. She was allowed no contact with men, and no luxuries, even wine. Augustus, deeply embittered, would never refer to her thereafter except as his ‘cancer’. Underneath his anger appears to have been very real hurt.