eBook - ePub

Organisational innovation in health services

Lessons from the NHS Treatment Centres

- 184 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Organisational innovation in health services

Lessons from the NHS Treatment Centres

About this book

Amid a welter of simultaneous policy initiatives, treatment centres were a top-down NHS innovation that became subverted into a multiplicity of solutions to different local problems. This highly readable account of how and why they evolved with completely unforeseen results reveals clear, practical lessons based on case study research involving over 200 interviews. Policy makers, managers and clinicians undertaking any organisational innovation cannot afford to ignore these findings.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Organisational innovation in health services by Gabbay, John,le May, Andrée,John Gabbay,Andrée le May,Catherine Pope,Glenn Robert,Paul Bate,Mary-Ann Elston in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Health Policy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

APPENDIX 1

Early definitions of a treatment centre

Treatment centres (TCs) were intended to deliver high volumes of high quality care using modern, efficient methods based on well-designed care-pathways. The key was separating elective from emergency care so that TCs could concentrate on delivering booked services according to planned protocols with the additional benefit of routinely offering patients choice and convenience. To achieve these aims, there was a guiding expectation that novel patient pathways would be planned that did not necessarily treat conventional departmental or professional boundaries as sacrosanct. The new model of care was expected to be innovative in focusing on the needs of patients rather than of the organisation and, where possible, providing a one-stop shop where the provision of diagnostic and treatment services improved both the efficiency of the service and the experience of the patient.

These defining characteristics of TCs were frequently reiterated in Department of Health and NHS material. Such sources also frequently repeated the point that there was no single model for a TC, whether run by the NHS or the private sector. Rather than a single model for all circumstances, TCs could be anywhere on a continuum from relatively simple primary care-based developments through traditional day case units to full blown elective ‘factories’ For example:

The term Diagnostic and Treatment Centres encompasses a wide range of healthcare activities and types of facility. (SDC Consulting, 2001)

Treatment Centres will vary in the types of services they offer depending on the local demand for health services. (Treatment Centres FAQ, originally at http://dh.gov.uk/PolicyAndGuidance/OrganisationPolicy, last accessed September 2006.)

For the NHS, DTCs [Diagnostic and Treatment Centres] offer an opportunity to adopt best practice and increase short term capacity through new ways of working. There is not one prescribed model for a DTC; for example it could be on NHS property or in a shopping centre. There are no set ideas on structure as long as the DTC is fit for purpose. Trusts may even want to consider leasing a facility and learning from how this works before building a tailor-made DTC. (Ken Anderson of the Department of Health’s independent sector TC team, quoted in Architects for Health, 2003)

The NHS Modernisation Agency, which had been set up to oversee and guide the modernising of the NHS (see Chapter Four) had the task of coordinating a collaborative programme to support these developments in TCs. By the time our study began in 2003, the Modernisation Agency’s website gave the following as a description of the core characteristics (the desiderata) of a TC:

The goal of a Treatment Centre is to deliver high quality, cost effective scheduled diagnostic and/or treatment services that optimise service efficiency and clinical outcomes and maximise patient satisfaction.

The defining characteristics of a Treatment Centre are that

(1) it embodies throughout its life the very best and most forward thinking practice in the design and delivery of the services it provides

(2) it delivers a high volume of activity in a pre-defined range of routine treatments and/or diagnostics

(3) it delivers scheduled care that is not affected by demand for, or provision of, unscheduled care either on the same site or elsewhere

(4) its services are streamlined and modern, using defined patient pathways

(5) its services are planned and booked, with an emphasis on patient choice and convenience together with organisational ability to deliver

(6) it has a clear and trusted identity that is valued by its patients and by its other stakeholders

(7) it provides a high quality, positive patient experience

(8) it creates a positive environment that enhances the working lives of the people who work in it

(9) it adds significantly to the capacity of the NHS to treat its patients successfully. (NHS Modernisation Agency, 2003c)

APPENDIX 2

The study design and methods

Sampling and site access

We used a multi-method case study design (Eisenhardt, 1989; Yin, 1994, 2003). We selected eight case study sites, using the preliminary information that we had gathered in preparation for the proposal. The selection of sites was also informed by meetings with the director and members of the NHS Modernisation Agency team responsible for the treatment centre (TC) programme. The sampling was intended to ensure that the case study sites provided a broad representation of the range of TCs either existing or in development as at March 2003 when the research began.

The selection characteristics that we considered were:

• geographical (for example, urban/rural);

• type of host trust;

• organisational (for example, integral or separate from host trust; NHS ‘star rating’ of host trust; likelihood of foundation hospital status);

• intended case mix (such as single or multiple specialty, routine or more complex cases);

• the stage of development (from those that were already open, through to those in the early planning stage);

• scale (as measured in terms of planned numbers of patients);

• new/purpose-built or not;

• degree of private sector involvement;

• commissioning model (such as whether reliant on multiple or single commissioners).

Ethical approval for the study was sought from a Multi-centre Research Ethics Committee in January 2003, and full approval was granted on 14 April 2003 (MREC/03/07). Management approval for the study from the relevant NHS trust chief executive or TC director in each of the sites was then obtained.

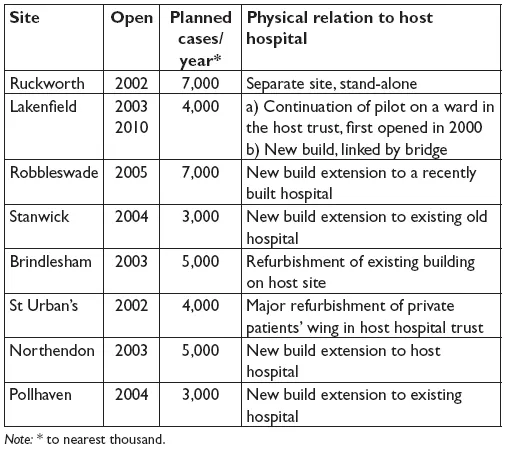

All but one of our original choices agreed to be case study sites (see Table A2.1). The sites were given an information sheet about the study. When they had accepted, a local ‘site representative’ was appointed from among the senior staff associated with the TC. With the help of this person, key initial informants in each site were selected for interview, based on their roles and involvement with the TC.

The sites selected ranged from relatively small initiatives (a single ward, Phase I of Lakenfield) to much larger enterprises including centres that operated essentially as a mini-hospital (Ruckworth and Robbleswade). Some were new purpose-built facilities (Robbleswade, Stanwick, Northendon, Pollhaven and Phase II of Lakenfield), some were refurbishments of facilities within the host organisation – usually a hospital (Brindlesham and St Urban’s) – and one (Ruckworth) was a separate leased building. The earliest date of opening was Lakenfield in 2000 with the latest (the same hospital’s Phase II) originally due to open in 2007/08, finally opening in 2010. The sites varied in terms of activity or scale as measured by the approximate number of patients intended to be treated per annum when the TC was fully operational (measured in ‘finished consultant episodes’). Ruckworth and Robbleswade were expected to have the highest activity, over double that of the smaller sites like Stanwick and Pollhaven. All the sites eventually selected were based in acute trusts and perhaps because of this most were in urban settings, although the geographical locations covered included city centres and towns near more rural and/or seaside areas. Robbleswade had major private sector involvement in the building work but was an NHS facility. The organisational status of the sites included trusts with between 0-3 stars and one was granted foundation hospital status during the course of the study; others were also in various stages of planning to do so.

The fieldwork, described more fully below, was undertaken over two-and-a-half years between mid-2003 and early 2006. It principally entailed organisationally focused interviews with key informants who were either involved in the design and delivery of the TC or in receipt of its services, direct observation of the TC’s workings (such as site development, TC meetings and educational events) and documentary review (including business plans, board minutes and annual reports). In addition, to contextualise our case study work, we undertook a comprehensive literature review of published and grey literature, some of which is reported in Chapter One, and kept abreast of relevant national policy changes (see Chapter Four).

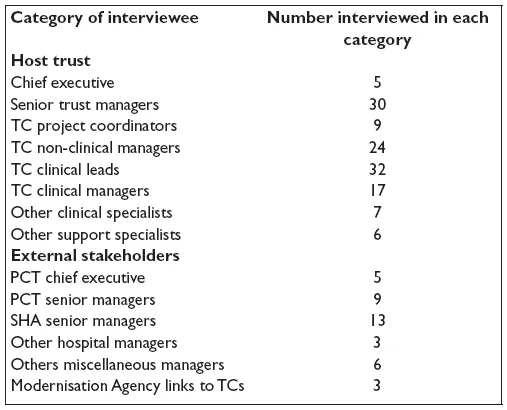

Fieldwork

We carried out the interviews in two phases, the first focusing on the internal organisation of the TC and its host trust, the second on members of the local health economy such as representatives of relevant primary care trusts (PCTs), strategic health authorities (SHAs) and neighbouring trusts. We used a snowball sampling technique in both phases, starting in phase one with the initial key players (such as the chief executive of the host trust and the TC manager or core team members) as identified by our site representatives. These early interviewees were asked to recommend other significant informants and so on until, again with the help of the site representative, we considered the sample to be complete across all the relevant parts of the system. We also consulted key personnel at the Modernisation Agency and several of our sites were members of NHS Elect, which led us to interview senior staff from this organisation as part of the second phase of our fieldwork (see Chapter Four).

Table A2.1: The sites

Interviews were semi-structured and were nearly all audio-recorded and transcribed. Most were face to face, sometimes with more than one interviewee at the same time. Where necessary, in a minority of instances, the interviews were done by telephone. We used a set of interview prompts to guide our approach throughout to ensure consistency between members of the research team.

We carried out 201 interviews in all, across a range of categories of interviewees, who may have been interviewed between one and five times (see Table A2.2).

Table A2.2: The interviewees

At most sites we also undertook opportunistic non-participant observation of:

• decision-making interactions (such as formal and informal networking within the TCs: project management meetings, clinical pathways design groups, staff ‘away days’ and training events run by external consultants; discussions between TCs and their parent organisation: trust board meetings which focused on TC-related topics such as capacity planning, case mix and complaints; discussions between the TCs and service users: patient involvement and open days; meetings between TC me...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of abbreviations

- Notes on the authors

- Introduction

- ONE: Transplanted roots: where the innovation came from

- TWO: Fertile ground? The organisational milieux of the treatment centres

- THREE: Taking up the challenge: local motives for the innovation

- FOUR: The impact of the wider policy context

- FIVE: Achieving the goals? How and why the treatment centres evolved

- SIX: Improving practice? Evidence of innovative ways of working

- SEVEN: Summary and conclusions: making sense of what happened

- EIGHT: Implications for policy, practice and research

- APPENDIX 1: Early definitions of a treatment centre

- APPENDIX 2: The study design and methods

- References