![]()

TWELVE

The concept of integrity in relation to failing and marginal students

Cherie Appleton and Carole Adamson

Introduction

This chapter considers the issue of how social work programmes can best support students deemed marginal or identified as at risk of failing. Using the lens of ‘integrity’ as a conceptual focus, it addresses the context in which fitness to practise is determined and the processes by which schools of social work may identify, support and manage issues of competence and practice standards. Questions that practice educators may use to determine the extent of concerns and possible options for resolution are applied to a case study and some typical vignettes are offered for reader exploration.

The practice of social work education spans academic and professional perspectives on student achievement, competency, standards and appropriate behaviour. Social work educators – in particular, those involved in practice learning – have first-line responsibility for determining who becomes a social worker (Elpers and FitzGerald, 2012; Robertson, 2013). Ultimately accountable to the individuals, families and communities with whom social work practises, social work programmes become the often-contentious territory where the determination of fitness to practise is most commonly exercised. While academic benchmarks for passing and failing are embedded within all tertiary programmes, an integral component of social work education is the applied professional definitions of competence, capability and standards of practice. Determination of fitness to practise based on judgements concerning a student’s conduct, values and ethics, communication skills, or physical or mental health is a far more complex and (some would contend) less objective process. It is a judgement call that presents immense challenges for those tasked with identifying and addressing the issues within social work programmes and practice learning settings (Staniforth and Fouché, 2006), and it is this contested territory that is explored within the chapter.

A note about the concepts and terminology used here is necessary: we make the assumption that the coordination of practice learning and teaching occurs within tertiary education and that preparation for practice occurs within the academy, with exposure to practice sited within the agencies and organisations with whom the schools of social work partner. Practice teachers, in a New Zealand context, are sited within education and we engage with fieldwork supervisors or fieldwork educators who mentor, support and contribute to the assessment of students within the practice agency but who are employed primarily as social workers within and by the field. Funding systems (or lack of) dictate that supervisors in the field offer their services free, so the onus ‘down under’ in Aotearoa New Zealand is on the academy to provide the preparation and final assessment of a student’s practice. Supervisors in the field have the responsibility of naming issues and alerting students and the social work school of any concerns that may lead to student failure. While decision-making in partnership is the preferred practice, the ultimate responsibility for excluding, removing from practice and failing a student rests finally with the academic institution. For those readers more accustomed to the active employment of practice teachers by social work provider agencies, our points about partnership and collaboration between educators and practice will hopefully maintain their strength despite the different balance in the relationship.

This collaborative implementation of social work professional standards requires a complex stakeholder partnership that may vary from country to country, while demonstrating the involvement of several key players. Determination of fitness to practise is made in the relationship between the academy, the sites of practice in both practice learning and employment environments, the professional bodies acting as voices of the profession (which may, in some jurisdictions, have the role of accrediting programmes), and the state. The state usually funds tertiary education and (in the jurisdictions in which social work is a registered profession) recognises and accredits social work programmes. Within our own practice field in Aotearoa New Zealand, the academic and practice elements are encapsulated by the phrase ‘fit and proper’, as defined by the Social Workers Registration Board (SWRB), a state body that both registers social workers and recognises social work programmes (SWRB, 2013). The challenge for educators is to determine a graduate’s fit and proper status in a manner that addresses statutory, professional and student expectations.

Using the conceptual framework of ‘integrity’ as a lens, this chapter addresses the issues of at-risk students and their potential failure within the context of these multiple, and often competing, demands and expectations of academia, government, society and professional standards. It concludes by applying an understanding of integrity to examples of possible scenarios with which the reader may be familiar.

Applying the lens of integrity in relation to social work competence and the marginal student

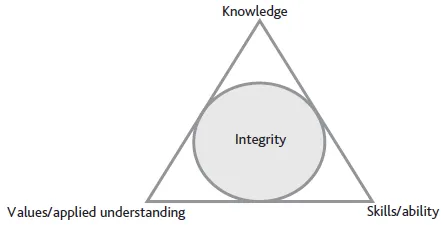

Social work programmes are required to graduate students with both sufficient academic understanding of the knowledge bases deemed appropriate for the profession and with an assessed quality of fitness to practise exemplified not only by academic achievement, but also by the demonstration of values and skills deemed compatible with the profession. Ife (2010: 223) comments that each of these three components (knowledge, values and skills) ‘is important in its own right and each also interacts with others’ as social work is not a technical process without values. In compatible terminology, Furness and Gilligan (2004: 469) describe competence as an equation of ‘ability + knowledge + understanding’; in this chapter, we are using the concept of integrity to describe the integral value-added combination of these competency factors as we believe that this addresses the holistic, subtle but fundamental requirement for good practice (see Figure 12.1).

Figure 12.1: Integrity in relation to social work knowledge, values and skills

Integrity is a term that occurs frequently within social work literature concerning standards, competency and capability. It is often applied broadly without definition, as if integrity is synonymous with good social work practice. Within the Code of Conduct issued by the SWRB in Aotearoa New Zealand, there is a requirement that social workers ‘uphold high standards of personal conduct and act with integrity’ (SWRB, 2014: 4). Similarly, the Code of Ethics of the British Association of Social Workers (BASW) describes professional integrity as a value, stating that ‘social workers have a responsibility to respect and uphold the values and principles of the profession and act in a reliable, honest and trustworthy manner’ (BASW, 2012: 10) – comparable statements are contained within Australian and North American codes.

Further use of the concept of integrity imbues it with additional meaning, suggesting a binding together of compatible qualities within a coherent whole. Appleton (2010: 13) summarised the literature base and concluded that there is ‘a re-occurring theme of integrity consisting of honesty, congruity and consistency with a person’s morals, ethics, principles, values and actions’. In other words, the concept of integrity manifests in both espoused beliefs and ethical principles (alongside adherence to an external ethical code), and in actions. Embedded as it is within the contexts and processes in which social work occurs, a systems perspective applied to integrity suggests that it has a fluid and multiple identity, with strength derived from the relational connections between its elements and a vulnerability to erosion should some of these elements be either not sufficiently developed or robust and come under threat. Given the constant demands of complex social work activity and the changing contexts in which we practise, a constructivist lens further enhances our appreciation that to have and maintain integrity requires us to view it as a social virtue that is defined primarily by our relationship with others (Calhoun, 1995), and that is neither fixed nor immovable (Cox et al, 2003). From an indigenous Maori perspective in Aotearoa New Zealand, one of the participants in Appleton’s research defined integrity as ‘three simple words in Maori which [are] tika, pono, aroha[1]; and they mean to be right, to take the right action and to always do it with genuineness and heart’ (Appleton, 2010: 82).

Addressing the issue of failing or marginal students

Tasked with the responsibility of graduating ‘fit and proper’ social workers, qualifying social work programmes are frequently under the spotlight of political and ideological debate over the role of our profession. Debate extends not only to graduates, but also to the programmes themselves, with the Social Work Taskforce in Britain in 2009 stating that ‘Specific concerns have been raised about the … robustness and quality of assessment, with some students passing the social work degree who are not competent or suitable to practise on the frontline’ (SWTF, 2009: 24).

Publication of the Narey (2014) report into the education of children’s social workers in the UK appears to have raised the ante in the quality and standards debate, with similar concerns expressed by politicians in New Zealand, such as Minister of Social Development Paula Bennett’s statement to the SWRB conference on 11 November 2013: ‘It is time that we started asking questions as to what are we training, how are we doing it, what are the skills they are leaving with, where are the checks and balances?’ (Bennett, 2013).

The Narey report and other critiques of the ‘fit’ between social work education and the demands of government agendas can be characterised as part of the wider ideological debate between neoliberal aspirations (reflected in the move towards competency-based training) and the social work profession’s construction of its professional identity, as demonstrated in discussions promoting critical reflection, such as Eadie and Lymbery (2007), Morley and Dunstan (2012) and Van Heugten (2011). The issues that individual schools of social work face in regard to excluding or supporting at-risk students need at times, in our opinion, to be viewed within this wider quality and standards debate. As educators, we are tasked with making these decisions within the context of practice learning and teaching and this requires clarity as to the professional purpose of the gatekeeping. As with the wider role of social work, decision-making about fitness to practise lies at the intersection of the personal, professional and the political, and it requires a coherent understanding concerning who is deemed at risk of failure, what criteria are used and what procedures and processes are activated and invested in to support marginal students.

The sometimes disparate elements of assessing fitness to practise within a social work programme – academic success, practice skills and the demonstration of professional values and behaviour – are exercised within all components of a social work programme. Traditional curriculum delivery, as exemplified by discrete papers or courses within the stages of a degree, has tended to emphasise the academic achievement of students at the potential expense of the assessment of the more applied and professional aspects of fitness to practise. Integration of student abilities may be marked through combined assessment of theory and skills, or some other form of gatekeeping prior to practice learning occurring. However, the siloed construction of tertiary degrees can potentially result in, for example, the academically bright but ethically challenged student or the academically challenged but emotionally and socially intelligent student progressing unchecked through a substantive part of their degree without being offered appropriate support and guidance. It can potentially result in an overreliance on practicum coordinators, practice educators and supervisors to name issues that have manifested themselves throughout a student’s academic journey. It can be argued, therefore, that the identification of and support for at-risk students might be better and earlier integrated within a degree constructed around practice learning and critical reflection (Adamson, 2011).

Defining failure and marginality is therefore located at a very busy intersection of academic and professional standards, within a bigger picture of political and ideological tensions, not the least being our profession’s values of social justice, equal opportunity and the belief in an individual’s capacity for change. It is important to recognise that the various terms ‘fitness to practise’, ‘professional suitability’, ‘suitability to practice’, ‘good character’, ‘morally and ethically sound’ and ‘fit and proper’ are all used in different ways and interpreted differently by individuals in practice (Currer and Atherton, 2008). Definitions of acceptable standards and behaviour may vary from programme to programme (Staniforth and Fouché, 2006).

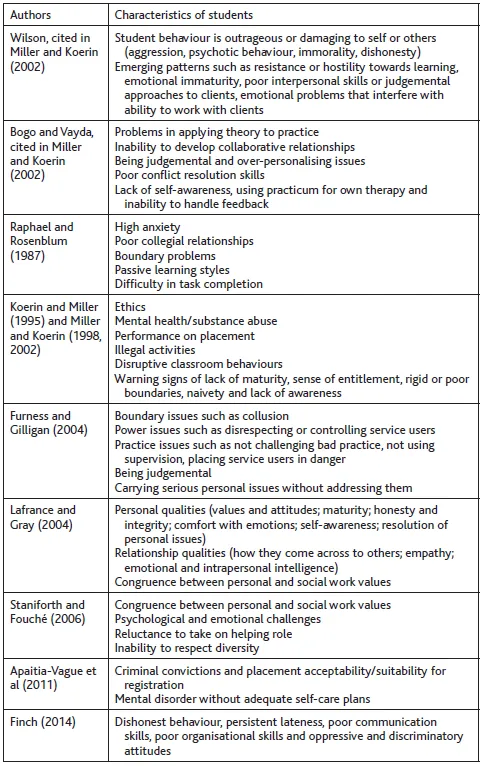

A literature review (see Table 12.1) has identified issues that may cause a student to fail or to be considered marginal; the points attributed to the named authors are only some of those raised.

Table 12.1: Issues related to marginality and failure in social work students

From the brief survey in Table 12.1, it can be seen that the issues arising for students and those assessing them lie not just in academic performance (although literacy and written communication skills are fundamental), but in the development of appropriate interactive, relational and values-based processes of engaging with service users, colleagues and the understanding and practice of professional identity. Also, of note in the literature is an increased emphasis on regulation and prescription, in parallel with a focus on the relational. While personal qualities and relational abilities are addressed throughout the literature, there is clearly a growing emphasis on the inclusion of equity issues and inclusive practice both for students and for the communities they will work with, for instance, Sin and Fong (2009) in relation to disability. There is, therefore, an imperative for professional programmes to be able to articulate, demonstrate, model and create learning opportunities for students to understand the expectations of growing their professional fitness to practise throughout the degree. These experiences need to enable students to build from an academic knowledge base to experiment, acquire and practise the behaviours, actions and attitudes necessary to become a professional beginning social worker practising across a variety of fields and in different contexts. It is the integration of the qualities of knowledge, the applied understanding of social work values and of social work skills, that we are terming ‘integrity’, the development of which is to be identified, assessed, supported, nurtured and monitored throughout a student’s social work programme. From the working definition of integrity as espoused beliefs, personal qualities and traits, social work ethics, knowledge, and skills in action, the first challenge to practice educators becomes how students can be assisted to recognise and own integrity. The second challenge is to discover how integrity can be assessed fairly: in what ways can all parties contribute to cultivating, and systemically supporting the exploration and maintenance of integrity within the student’s educational and personal/professional journey? What follows is an exploration of how integrity as an applied framework can be used to assist growing student practitioners’ understanding, devel...