![]()

FOURTEEN

Social Democratic reforms of the welfare state: Germany and the UK compared

Martin Seeleib-Kaiser

Introduction

Social Democrats regained power in the UK and Germany in the late 1990s, after long periods spent in opposition. This chapter takes stock of welfare state reforms in both countries and aims to answer whether, and how far, 10 years of Social-Democratic governments have left their modern imprints on the institutional set-up of the welfare state, based on Hall’s categorisations of change (1993; see also Chapter One, this volume). As the dimensions of ‘modernisation’ identified by 6 and Peck (2004) are largely peculiar elements of the UK modernisation process, I will refrain from operationalising these in comparative analysis here. A common thread of ‘modernising’ welfare state arrangements in both countries, however, has been the focus on reducing the dependency ratio and increasing employment rates, while at the same time highlighting the need for social justice. This approach to modernisation is in accordance with some of the elements outlined by Esping-Andersen et al (2002). After briefly sketching out the socioeconomic conditions and institutional design of the two welfare states in the late 1990s, this will serve as a reference point for further analysis. I will elaborate in greater detail on the main elements of the common modernisation themes, before addressing the various reforms in the domains of (un)employment, pensions and family policies. This chapter is limited to these three domains because, firstly, they constitute the core dimensions of mainstream comparative welfare state regime analyses (cf Esping-Andersen, 1990, 1999), and, secondly, space limitations do not allow for a more comprehensive analysis. In conclusion I aim to assess these reforms in the light of the research question.

Socioeconomic conditions and institutional welfare state design in the late 1990s

According to widely accepted categorisations, Germany and the UK are said to have very different forms of capitalism and welfare state arrangements. Germany belongs to the Conservative/Christian-Democratic welfare regime, relying primarily on social insurance, while the UK is usually characterised as a Liberal welfare state, relying primarily on the market and means-tested benefits (Esping-Andersen, 1990, 1999). While the main aim of the German unemployment and old-age pension schemes has been to achieve social stability and cohesion (mainly through guaranteeing the individually achieved living standard for unemployed [male] workers as well as pensioners), the main aim of the largely means-tested UK transfer system has been to alleviate poverty (cf Goodin et al, 1999). Despite these differences, both countries have promoted the strong male breadwinner model, which has had significant implications for female labour force participation and the provision of childcare (Lewis, 1992).

As a consequence of economic collapse following German unification and the subsequent steep increase in unemployment, extending the West German welfare state to the East, while continuing to rely on social insurance contributions as the main financing mechanism, led to an unprecedented increase in social insurance contributions. These subsequently not only exerted pressure on those German companies engaged in the global economy, but overall increased the tax wedge, primarily limiting the growth of jobs in the less exposed service sectors (Scharpf, 1995). From a social policy perspective the expansion of the social insurance system to the East was successful in the short term, as it provided quite generous financial means to those who had become unemployed or retired (early) as a result of the severe labour market adjustments after 1990, thereby effectively limiting the extent of poverty. However, sharply increased social insurance contributions and the reluctance to raise income taxes to finance the adjustment costs associated with German unification triggered retrenchment policies in the domains of the unemployment and old-age insurance system only a few years later. For the unemployed the reforms meant a reduction in replacement rates and a tightening of conditionality rules. Whereas benefits for current pensioners were largely left unchanged, the Conservative–Liberal coalition government significantly reduced the replacement rate for future pensioners of the baby boom generation. Thus both policy areas saw a withdrawal from the once guiding principle of publicly guaranteeing the achieved living standard. At the time, these reforms were vehemently opposed by the Social Democrats, who characterised them as unnecessary and unfair (Bleses and Seeleib-Kaiser, 2004).

With regard to family policies, the Christian Democrats have pursued an expansionary policy since the mid-1980s. The various measures included the introduction and subsequent expansion of parental leave and a parental (leave) benefit, as well as child-rearing credits in the old-age social insurance scheme. Furthermore, the introduction of an entitlement to a place in a childcare facility for every child between the ages of three and six led to a significant expansion of services in the second half of the 1990s (Bleses and Seeleib-Kaiser, 2004). Although we witnessed a steep and almost continuous increase in unemployment (with an increasingly high percentage of long-term unemployed), the poverty rate (based on 60% of median income) only increased marginally, from 12% (1993) to 13.1% (1998), despite the huge structural adjustments associated with German unification (Seeleib-Kaiser, 2007, p 28).

During the long tenure of the Conservatives in government, the British welfare state became (more) Liberal. Within pension policies the earnings-related programme was more or less eliminated and the benefit level of the universal Basic State Pension continued to be insufficient to lift pensioners out of poverty. After deregulating the labour market in the 1980s (Howell, 2006), the Conservative government in 1996 eventually replaced the earnings-related unemployment insurance benefit with a flat-rate Jobseeker’s Allowance, with benefits set at the social assistance level and conditional on accepting basically any legal job offer (Clasen, 2005). In order to strengthen work incentives, in 1988 the government introduced the so-called ‘family credit’ that provided in-work benefits for poor families (Funk, 2007). Overall, an explicit family policy going beyond the provision of child allowances or tax credits was not perceived to be within the responsibility of the state. Partly as a result of these social policies, the socioeconomic situation in the UK differed remarkably from that in Germany at the time when Social Democrats gained power in the late 1990s. Although unemployment had started to decline in the mid-1990s, a significant proportion of the workforce was occupied in low-paying jobs;1 poverty, and especially child poverty, increased significantly during the Conservative tenure in government. In the mid-1990s, the UK was one of the most unequal societies in the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) world; its Gini coefficient was higher than in any other rich country except for the US. Its overall poverty rate (defined as 60% of median income) stood at more than 20% (LIS, 2007).

Modernising the welfare state

Despite these socioeconomic and institutional differences, both Social Democratic parties developed similar themes with regard to ‘modernisation’, as they repositioned and rebranded themselves ‘New Labour’ and the ‘New Centre’ (Die Neue Mitte) (see also Hudson et al, 2008). In the election campaigns both parties pledged that they would be fiscally ‘responsible’, while at the same time they aimed to achieve a more just society through greater opportunity. Although the state was said to play an important role in achieving this goal, both parties emphasised the potential benefits of the market and market mechanisms. While increasing the employment rate was a key element, the state should mainly function as an enabler by ensuring that ‘work pays’ and reducing non-wage labour costs through structural reforms. In accordance with the emphasis on activation instead of compensation and the promotion of greater self-reliance, all benefit recipients were to be assessed for their potential to earn. Finally, both parties highlighted the need to help parents balance work and family life (cf Labour, 1997; SPD, 1998; Blair and Schroeder, 1999).

An analysis of the 1998 party manifesto of the Social Democratic Party (SPD) clearly shows that it did not intend to expand the welfare state in the medium term, despite promises to revoke some policy changes of the prior Conservative coalition government in the short run. Social Democrats committed themselves to ‘budgetary discipline’ and the aim of reducing the public debt. Within such an environment there would be no room for deficit-financed employment policies. The Social Democrats had made it explicit in their election manifesto and later stated it again in their coalition agreement with the Alliance90/The Greens that they would reform the old-age insurance system with the goal of expanding private and company-based pension plans as key elements. This approach was part of their broader strategy towards self-reliance, which also included a call for ‘work instead of assistance’, that is, a reform of the various support programmes for the (long-term) unemployed and an increased emphasis on activation. In addition, they called for a reduction of social insurance contributions as a means to promote job growth. Finally, in terms of family policy the party manifesto proposed improvements of parental leave provisions, an expansion of the child allowance and tax credits, as well as an expansion of childcare facilities. Instead of using the term ‘modernisation’, German Social Democrats used the term ‘innovation’ as their buzzword (SPD, 1998; cf Seeleib-Kaiser, 2004).

Going beyond the pledge of German Social Democrats, New Labour not only limited itself to refrain from a Keynesian approach to full employment and to stress the need for sound public finances, but explicitly committed itself to the spending limits set by the Conservative government for the first two years. Although the manifesto was very vague on specific commitments with regard to tackling the high levels of poverty, it did mention it in relation to reducing welfare dependency by reforming the tax and benefit system as well as helping people into jobs (cf Stewart and Hills, 2005). As Toynbee and Walker (2005, p 7) put it: ‘social justice had barely been mentioned at election time, for fear of alarming middle England’. The key theme of New Labour’s social security reform initiatives has been the promotion of paid employment, that is, to create incentives for employment and to ‘make work pay’ (Kemp, 2005, pp 17-18). This also included a National Childcare Strategy to help parents balance family and work life (Labour Party, 1997). After two years in government, Prime Minister Tony Blair unexpectedly announced: ‘ours is the first generation to end child poverty forever. It is a twenty year mission but I believe it can be done’ (quoted in Stewart and Hills, 2005, p 11). In addition to fighting child poverty, reducing poverty among pensioners became a priority (Stewart and Hills, 2005, p 11). However, it must be emphasised that Labour did not intend to pursue a comprehensive redistributive approach despite the internationally very high levels of inequality and poverty. As Blair stated: ‘justice for me is concentrated on lifting incomes of those that don’t have a decent income. It’s not a burning ambition of mine to make sure that David Beckham earns less money’ (quoted in Sefton and Sutherland, 2005, p 233).

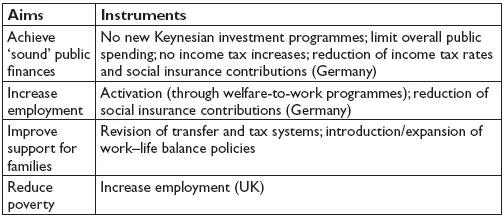

The various elements of the Social Democratic approach towards ‘modernisation’ in both countries are summarised in Table 14.1.

Table 14.1: Social Democrats’ aims and instruments of ‘modern’ welfare states

Social Democratic welfare state reforms in Germany and the UK

Welfare state reforms in Germany

During the first four years of the Red–Green coalition government no major reforms were enacted in the areas of active labour market policy, unemployment insurance or social assistance. The work on a comprehensive pension reform proposal, however, started very early in the tenure of the Red–Green coalition government. The main aim was to limit future social insurance contributions for pensions to ...