![]()

ONE

Navigating the knowledge–policy landscape

Understanding the links between knowledge, policy and power in development

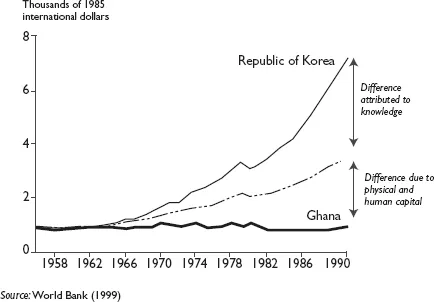

Knowledge is increasingly seen as a critical component of development. As early as 1998/99 the World Development Report emphasised the need for greater access to better quality knowledge in addressing development challenges, from infant mortality to agricultural growth. Indeed, the difference knowledge may make to poverty reduction is highlighted by the starkly different development trajectories (measured by per capita gross domestic product (GDP)) of South Korea and Ghana since the 1950s. While the former is now a fully fledged member of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and itself a donor country, the other graduated to lower middle-income country status only in 2011 (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1: The potential of knowledge in development

Over the past decade, however, there has been growing recognition by a broad array of development actors that there are no magic bullets to strengthen the knowledge–policy interface; instead, better systems and channels are urgently needed to harness existing and new knowledge sources so as to provide strategic, feasible and timely policy and programme solutions.1 In particular, academic knowledge can play a useful role in shaping the thinking of policy actors and practitioners over time (Weiss, 1977), while policy research has the potential to have far-reaching impacts on programme design and budget allocations, with tangible impacts for those who are poor and marginalised. A case in point is the rigorous evaluation work carried out around Mexico’s conditional cash transfer programme, Progresa/Oportunidades: findings have been utilised to secure greater investments in safety nets for poor people, not only at the national level, but also in similar programmes across Latin America, Asia and Africa. These now reach tens of millions of poor households (Behrman, 2007), and are continuing to expand on account, at least in part, of the robust knowledge base that is being generated on the strengths and weaknesses of many of the programmes (Fiszbein and Schady, 2008).2

Such cases of fruitful evidence-informed policy influencing are not the norm, however. Identifying what accounts for effective knowledge uptake in developing country contexts is a critical challenge if we are to ensure that the millions of pounds invested annually in knowledge generation contribute to more informed policy dialogues. The UK Department for International Development’s (DFID’s) Research Strategy Consultation Process in Africa in 2007, for example, highlighted a range of key concerns, including:

- a dearth of mechanisms to articulate and channel demand for knowledge/research;

- problems of knowledge fragmentation, weak coordination and limited public access;

- the need for greater end-user involvement throughout the research process to counter supply- and often donor-driven research;

- a strong demand for problem-oriented, policy-relevant research; and

- capacity-building support to enable research users to better specify their knowledge needs (Romney et al, 2007).

Focusing on research uptake will not, by itself, strengthen the interface between knowledge and policy; research is an important but by no means the only component. Local contextual knowledge and knowledge from practice are equally necessary if policymakers at all levels are to make robust, reasoned judgements about how to make change happen. Choosing which types of knowledge to use and how to use them is complex because of the different political contexts in which policy is made and the wide variety of actors who could be involved in the policy process. Our collective understanding of how to address these challenges is growing, but remains in a fledgling state.

This book aims to address this gap by providing a practical guide to understanding how knowledge, policy and power interact to promote or prevent change. As the quote at the beginning of this chapter suggests, we acknowledge that, although some models provide useful analyses of some aspects of the interface between knowledge and policy, it is impossible to construct a single one-size-fits-all template for understanding such a complex set of relationships. Descriptions of the knowledge–policy landscape are also highly variable (depending on where and how you look at it and whom you talk to), and it can be difficult to navigate them unless time is taken to reflect systematically on specific dimensions. We therefore seek to provide readers with ways to identify and recognise problems that have hampered previous attempts to improve the knowledge–policy interface, such as persistent asymmetric relations between actors, crude assessments of political context, heavy-handed compression of incompatible types of knowledge and mistranslations of knowledge. Most importantly, the book aims to provide readers with academically rigorous yet practical guidance on how to develop strategies to negotiate the complexity of the knowledge–policy interface more effectively, so as to contribute to policy dialogues on key development goals. Box 1.1 sets out definitions of the key concepts we use in the book. Our focus is primarily on the dynamics of the knowledge–policy interface in international development, but we believe our general approach is also applicable to a broader array of policy arenas.

Box 1.1: Key definitions

Policy: we define policy as a set of related decisions that give rise to specific proposals for action or negotiated agreements. ‘Public policy can result in concrete plans …, specific proposals for action including regulation, economic instruments such as subsidies or taxes, or programmes of legislation with accompanying organizations and resources. But it does not only encompass these sorts of legislated actions. “Policy” may also result in voluntary negotiated standards … risk governance …, decisions about the allocation of public funds via research prioritization, [and] the provision of information to “win hearts and minds”…. Policy cannot be characterized by a single decision point. Instead, it is a series of decisions – one of which may be crucial in determining the ultimate direction of the policy – but all of which contribute to how it is planned and implemented’ (Shaxson, 2009, p 2142).

Policy process: the definition of policy processes used in this book is broad, with an understanding that there is seldom a specific decision point in the policy process; rather, a series of decisions summarily contribute to change. Hence, our definition is that the policy process is one of ‘translating political vision, through a variety of methods and decisions, into concrete plans or negotiated agreements’.

Knowledge: Perkin and Court (2005, p 2) define knowledge as ‘information that has been evaluated and organised so that it can be used purposefully’, but there are historically different points of view about the content of knowledge, how knowledge is connected to truth and where it is held. Positivists such as Popper argue that knowledge functions primarily to describe the world, proposing theories that make predictions and testing them through experiments and direct experience. Kuhn argued against this, suggesting that worldviews or paradigms frame individual experience and shift as a result of collective value judgements as to which paradigm better fits wider values and belief systems. Further, Wittgenstein demonstrated that meaning and understanding are inseparable from language and ‘doing’, while Foucault observed that power infuses the processes of generating and using knowledge. Our conception of knowledge holds that the processes of evaluating and organising it are strongly influenced by power dynamics, values and belief systems. This means knowledge cannot be an external input to the policy process: instead, its production and use are interwoven in an ongoing and continually changing discourse, within the politics and power dynamics of policy making.

Power: we use Lukes’ (1972) threefold conceptualisation of power – as overt, covert and hidden – as our starting point. Power can be about the exercise of material resources in order to secure a desired change or position; negotiating institutions, norms and conventions, including the formal/informal ‘rules of the game’ or ways of doing things (see North, 1993); or the ability to shape other actors’ preferences (drawing on Foucault’s notion of power as discourse and embedded in socially constructed values and ways of seeing the world).

Knowledge–policy interface: an interface can be considered the point of interaction between two systems of work, or more appropriately ‘a critical point of intersection between life-worlds, social fields or levels of social organisation, where social discontinuities, based on discrepancies in values, interests, knowledge and power, are most likely to be located’ (Long, 2001, p 243). Consequently, the knowledge–policy interface is best thought of as the arena in which information is filtered, brokered and transmuted through various lenses, whether these be political, social or economic, into a set of related decisions that eventually result in concrete plans or negotiated agreements.

The key contributions of this book

It is not the intention of this book to contribute yet another model to the canon of work on the knowledge–policy interface; a brief history of the evolution of thinking about the knowledge-to-policy process shows that each iteration contributes significant insights yet cannot explain the entirety of the process. For example, the ‘linear’ or ‘mainstream’ policy process model of the 1950s/1960s envisioned a regular cycle of agenda setting, formulation, implementation and evaluation, driven and informed by knowledge, irrespective of the issue at hand (Lasswell, 1951). From this emerged the evidence-based policy movement, which sought to develop frameworks to understand the drivers of and barriers to research ‘uptake’,3 with the normative goal of increasing the influence of research on policy making. This has in turn given rise to a tendency for evidence-based policy studies, especially in the health sciences and economics, to prioritise some research techniques over others, setting experimental methods as the ‘gold standard’.4 However, although the linear model is often criticised for paying less attention to more qualitative and participatory sources, such as public service users’ views and local knowledge (Tilley and Laycock, 2000; Rycroft-Malone et al, 2004), we argue that it made an important contribution by sowing the seeds of the current focus on ensuring the disciplinary quality of research-based and other forms of knowledge.

Critics of the evidence-based approach emphasised the political and epistemological dynamics of the production and use of particular sources of information (Luke, 2003; Marston and Watts, 2003) and shifted the focus from supposedly value-free evidence to the more complex and value-laden concept of knowledge (Sanderson, 2004), with the inherent and power-laden question: ‘whose knowledge counts?’ (Chambers, 2005). With this shift emerged a range of models that not only dealt more explicitly with questions of power, but also sought to encompass a broader array of non-state actors and networks and place greater emphasis on iterative processes and policy spaces. All of these offered insights into the importance of understanding the political context surrounding policymaking and the power relations among actors.

How these different models were applied in various sectors is beyond the scope of this book. However, it is worth noting that, from the 1990s onwards in the agricultural and health sectors,5 work on the links between research, policy and practice emerged that emphasised the importance of appreciating the user’s needs for knowledge (both in form and in content) and developing new structures to facilitate the flow of knowledge between the different groups of actors. This emphasis on knowledge interaction highlighted the need to forge partnerships between knowledge ‘producers’ and ‘users’ that recognise the ‘co-construction’ of policy knowledge (Lavis et al, 2006), including developing a shared understanding of what questions to ask, how to go about answering them and how best to interpret the responses.

Interest in the knowledge–policy interface continues to burgeon, as underscored by the increasing emphasis on the importance of strengthening the generation and application of rigorous evidence to policy decisions.6 This interest can be seen in (for example) current reforms to the UK DFID’s project approval processes, which require that funding applicants make an assessment of the strength of the evidence underpinning their work; these assessments in turn affect the requirements for subsequent evaluations.7 It can als...