![]()

PART ONE

CONSCIOUSNESS

![]()

TWO

Mapping the landscape

‘Innovation is a terrible word. But there’s nothing wrong with its content.’ (MindLab, 2010)

Many would probably agree with the quote above, which is from the communication strategy we established at MindLab. Much like the term ‘design’, ‘innovation’ is so all-encompassing and open to interpretation that it risks losing its meaning (Stewart-Weeks, 2010). Perhaps that is why it is almost a given at innovation conferences and seminars that some participant will eventually ask ‘how do you define innovation?’

As discussed in the Introduction, public sector innovation has evolved over a number of stages during the last four decades or so, the momentum picking up pace, the discourse changing from ‘what’ to ‘how’. Today, most public leaders tend to agree that more positive change is needed in government, as societal challenges ranging from ageing to chronic illness to increasing productivity pressures are mounting. What is more difficult to articulate is what innovation is, exactly, and in what way it is relevant and meaningful to the organisation.

So, we do have to start with some definitions. Their number is of course massive. The amount of literature focusing on innovation in the context of business management and entrepreneurship is huge and growing by the week. Arguably, it started with the Austrian-born economist Joseph Schumpeter, who famously characterised innovation as ‘creative destruction’. He linked innovation to the rise of capitalism as the fundamental impulse that kept capitalist society in motion through the creation of new consumers, new goods, new methods of production, new markets and new forms of industrial organisation (Schumpeter, 1975, pp 82–5). Subsequent business thinkers like the late C.K. Prahalad, Clayton Christensen, Gary Hamel, Eric von Hippel, John Bessant and Henry Chesbrough have expanded significantly on the concept of innovation, adding new dimensions and layers onto the fundamental notion of ‘newness’.

Uncovering how the insights of these thinkers, and others, might apply to the complexities of the public sector across sectors, levels and national cultures is no easy task. So why even try? Because, as should already be clear, innovation is critical to addressing how the public sector can better respond to the massive and complex challenges facing our societies, just as it is critical to businesses seeking the next source of competitive advantage. Strategic, sustainable, ongoing innovation activity, as opposed to one-off hits or misses, requires awareness. As British professor Fiona Patterson, who studied everyday innovation practices across more than 800 companies, said, ‘Our results showed that organisations that clearly articulate what is meant by “innovative working” are more likely to be successful in their attempt to encourage innovative behaviours’ (Patterson et al, 2009, p 12). Without a vocabulary, it becomes close to impossible for managers to communicate, support and empower staff to meaningfully undertake innovation activities. But that doesn’t mean that innovation can’t happen anyway. The efforts are just fewer and a lot less effective. According to the UK’s National Audit Office (NAO), which has examined the innovation practices of the UK central government, confusion about the meaning and purpose of innovation among staff was among the key barriers to generating innovative ideas (NAO, 2009).

Further, to understand why innovation – and especially more co-creative and human-centred approaches to achieving it – is needed, it can be helpful to remind ourselves of the nature of the problems many public organisations are dealing with. In fact, that ought to be a starting point for our consideration of public sector innovation as an urgent priority: because many public problems are ‘wicked’ and complex in character, there is a sharpened need for managers and staff to access tools and approaches that are fit for the challenges at hand. This chapter therefore addresses the following questions:

• What kinds of problems do public organisations face?

• What is innovation in the public sector?

• Where does innovation come from?

• What types of innovation are there?

• What kinds of value can public sector innovation generate?

On the nature of public problems

What if a significant part of the challenges we face in government are of an entirely different class than our current institutions and approaches were designed for? This is a question that more and more public organisations are considering as they realise that, despite massive investments of time and money, many of the most urgent problems don’t seem to go away. Rather, new ones jump to the forefront while old ones remain as sources of expenditure and pressure on the public system.

The term ‘complexity’ is increasingly used to describe the types of problems facing government organisations. Complex characteristics, as opposed to complicated ones, refer to systems with large numbers of interacting elements; where interactions are nonlinear, so that minor changes can have disproportionately large consequences; which are dynamic and emergent; and where hindsight cannot lead to foresight because external conditions constantly change (Bourgon, 2011; Bason, 2017).

A potentially even more helpful way of distinguishing between problem types is between tame and wicked problems. Tame problems can be understood as well-defined, technical and engineering problems. These problems can be understood and addressed through an appreciation and careful, systematic assessment of their constituent parts. Although they may be extremely ‘difficult’ or ‘complicated’ (Bourgon, 2011, pp 20–1) or ‘hard’ (Martin, 2009, p 95), they can be addressed through careful analysis. Here, it is relevant for decision makers to draw extensively on knowledge of existing evidence and ‘best practice’ (Snowden and Boone, 2007). If one examines the language and concepts deployed by most public organisations, they tend to a very great extent to assume that problems are tame. Language like ‘doing what works’, ‘solving’ and ‘fixing’ problems resembles the language used by technicians and engineers – as if creating a high-performing school system is the same as building a railroad. The heavy focus on ‘big’ data and ‘analytics’ is also to some extent connected to the view that if only we had a large-enough calculator, we would find the ‘optimal’ ‘solution’ to the problem at hand.

But what if problems are not something we can rationally analyse and ‘solve’ in predictable ways?

Wicked problems were first characterised in some detail by the academics Horst Rittel and Melvin Webber (1973). They famously argued that a certain kind of problems are better understood through examining the interrelations and dependencies between their constituent parts, and by ‘probing’ to generate dynamics that reveal underlying and hidden relationships. Arguably, a great many public problems fall into this category. Wayne Parsons, an academic, has underscored the particular character of public problems by reminding us that the design of public policies is ‘a very different matter from that of designing for a moon landing’ (Parsons, 2010, p 17). A similar argument is put forward by Bill Eggers and John O’Leary (2009) in their aptly titled book If We Can Put a Man on the Moon … Getting Big Things Done in Government. The approaches needed to deal with wicked problems are fundamentally different and essentially require ‘probing’, experimentation, learning and adaptation (Snowden and Boone, 2007).

Originally, Rittel and Webber put forward 10 criteria to characterise wicked problems, the first among these being that they have no clear or final definition, and so can be continuously redefined. The original list contains some overlap and repetition; for the sake of clarity Martin (2009) suggests that, ultimately, wicked problems can be identified by four dimensions:

• First, causal relationships are unclear and dynamic. Root causes of the problem are difficult, if not impossible, to identify; they are ambiguous and elusive. Part of the reason for this confusion around causality is also that many public problems are ultimately behavioural. Scholars ranging from Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman in Thinking, Fast and Slow (2010), to Dan Ariely in Predictably Irrational (2009) and Thaler and Sunstein in their runaway success Nudge (2008) and Sunstein in his more recent Simpler (2013) have pointed out that human behaviour is not as easily understood as we might like to think, and cannot be predicted with much accuracy. Another part of the confusion around causality is more political. In a public sector context the root causes, and thus the very definition of the nature of the problem, can be highly prone to ideological contention: is immigration a problem or a resource for a society? It climate change a problem or just a manageable consequence of the quest for growth?

• Second, the problem does not fit into a known category; in fact there are no ‘classes’ of wicked problems. Snowden and Boone (2007) have argued that this implies that available ‘good’ or ‘best’ practices cannot be applied effectively as a course of problem solving. This poses particular and important limitations to the public management notion of ‘evidence-based policy’, which implies that policy decisions should be based on solid knowledge of ‘what works’.

• Third, attempts at problem solving change the problem. Devising potential approaches to the problem tend to change how it is understood; and implemented solutions are consequential in the sense that they create a new situation for the next trial; so all solutions are ‘one shots’. This is not least the case in the highly exposed domain of public policy, where as soon as stakeholders learn of potential ideas, plans, laws or initiatives, they start acting strategically and thus influence the policy landscape even before any action has been undertaken. This prompts the need for more iterative, nonlinear and possibly more inclusive approaches – what Halse et al (2010) call generative – ways of exploring and addressing the problem.

• Fourth, there is no stopping rule. Wicked problems do not have any firm basis for judging whether they are ‘solved’ or not; as Rowe (1987, p 41) formulates it, they have no ‘stopping rule’. Solutions cannot be judged as true or false, but merely as ‘better or worse’ (Ritchey, 2011, p 92). Whenever a solution is proposed, it can always be improved upon. Due to the indeterminacy of the problem definition, other problem definitions will always be possible, and thus entirely new solution spaces can be envisaged. In fact, one can question whether wicked problems can ever truly be ‘solved’. In a public sector context this issue is hardened by the many stakeholders often engaged in a particular policy field, which can have wildly divergent notions of what is ‘good’ or ‘bad’ – based not on empirical or ‘objective’ data, but based on ideology, power calculations or institutional interests. This is something I will discuss further in the next chapter, concerning the context of public sector innovation.

To conclude, there are strong arguments that the approaches needed to achieve innovative outcomes in the public sector must take account of the wicked and complex problem landscape. Only by recognising the underlying nature of public problems can managers identify the ways to best address them. That leads us to the next question: How do we define innovation?

Innovation: from idea to value

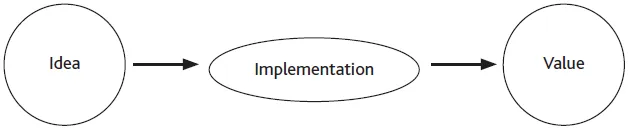

I define public sector innovation as the process of creating new ideas and turning them into value for society (Figure 2.1). It concerns how politicians, public leaders and employees make their visions of a desired new state of the world into reality. The concept of innovation therefore places a laser-sharp focus on whether the organisation is able to generate and select the best possible ideas, implement them effectively and ensure that they create value.

Figure 2.1: Innovation defined

Government organisations can take various roles in the innovation process – placing the emphasis, respectively, on the generation of creative new ideas, on their implementation or on the continuous delivery of value. The challenge for the organisation, and thereby for public leaders, is to consciously balance these different roles. In spite of the mounting pressure to embrace innovation, public sector organisations are usually much more comfortable with the right-hand side of Figure 2.1 – delivering the same type of value over and over, in the same way. Public bureaucracies are relatively good at maintaining stable models of production; not so good at designing new ones.

As Roger Martin, former dean of Toronto’s Rotman School and author of The Business of Design, has argued, this is also the case for private enterprises. Most large organisations are effective at delivering products and services according to algorithms – stable and precise specifications of how to carry out a certain process of production with high reliability (Martin, 2009). Mass production of public services, exploiting the high returns to scale of standardised, low-variance, high-volume delivery, has been one of the great successes of post-Second World War Western societies. From managing welfare payments to school systems and hospitals, standardisation has been the order of the day. But when the world changes, are our organisations ready to adapt? Are they able, where necessary, to embrace the more flexible ‘hybrid’ modes of production with the higher degree of individualisation required in a complex, networked knowledge society characterised by increasingly intractable and wicked problems? Can they identify and define the new approaches needed to battle spiralling welfare costs, failures in our educational systems and the cries for more individualised treatment of hospital patients?

Martin points out that most organisations are much less capable of exploring the ‘mystery’ of what might be – and discovering new approaches to creating value – than they are of executing the algorithm of 20th-century-style mass production. But the exploration of mystery is the starting point of innovation; a fact that many public organisations today are forced to...