![]() Part I

Part I

Research ethics in context![]()

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

Introduction

In the real world, ethical research requires an ongoing and active engagement with people and the environment around us. This book argues that research cannot be rendered ethical by completing a one-off administrative task, and explains why and how researchers and evaluators need to work in an ethical way throughout the research process. It advocates for a move away from the ‘do no harm’ ethical baseline inherited from biomedical research, and towards a social justice approach to research ethics. In doing this, it draws on both the Indigenous and Euro-Western research ethics literatures. The book also draws on interviews with researchers who have an interest in ethics, and a small number of meetings with Indigenous researchers. A further source is my own experience of learning about research ethics during my postgraduate studies for an MSc in Social Research Methods and later a PhD, and my efforts to act ethically in research practice in a wide variety of contexts since 1999.

Generally speaking, social researchers and evaluators are working to make the world a better place. Indigenous researchers acknowledge this (Smith, 2013: 91), and some Euro-Western researchers do too. However, there are economically driven pressures on Euro-Western researchers to stick with ‘do no harm’. This approach focuses on protecting the vulnerable, and so is easier and cheaper than the more proactive social justice approach that requires us to address the inequalities that create vulnerability (Williams, 2016: 545).

For researchers in Euro-Western societies, ‘truth’ is something that can be empirically verified (Alldred and Gillies, 2012: 142), while for researchers in Indigenous societies, ‘truth’ may exist in stories, experiences and relationships with ancestors (Chilisa, 2012: 116; Blackfoot Gallery Committee, 2013: 18). The Euro-Western approach has been to assert that our way of thinking about truth is the right way, which is in effect another imperialist attempt to colonise the world (Castleden et al, 2015: 12–13). Castleden et al, like Connell, argue that instead we need to aim for respect for and engagement with each other’s knowledges between societies. In Connell’s view, we need to think about social sciences, arts and humanities in global terms, and to offer to respectfully engage with each other’s knowledge systems, as a basis for mutual learning (Connell, 2007: 224). I would build on this to argue that we also need to aim to respectfully engage with each other’s knowledges within societies as a basis for mutual learning.

Research ethics is rarely a question of right and wrong; it’s more a matter of finding a multi-dimensional equivalent of the ‘line of best fit’. This book aims to show why research ethics involves more disagreements than agreements and more debate than consensus (de Vries and Henley, 2014: 84). Even the choice of a word can have ethical implications. For example, some Indigenous people are unhappy with the term ‘Indigenous’ being used to describe them (Passingan, 2013: 361). One danger is that using a single term in this way gives the impression that Indigenous peoples are one homogeneous group, which is certainly not the case (Wilson, 2008: 106; Kovach, 2009: 5; Cram, Chilisa and Mertens, 2013: 21; Ignacio, 2013: 162; Lambert, 2014: 38; Puebla, 2014: 176; Blalock, 2015: 59–61; Bowman, Francis and Tyndall, 2015: 344; Rix et al, 2018: 3). The term itself is contested, so for the avoidance of doubt I am using ‘Indigenous’ to mean peoples native to lands that have been colonised by settlers from other nations (Cram, Chilisa and Mertens, 2013: 16; Lambert, 2014: 1). Following Linda Tuhiwai Smith’s example (2012: 7), I will use the term ‘Indigenous peoples’ to reflect multiplicity, and ‘Indigenous’ to reflect the global aspect of my work. Where I refer to a specific nation, community or tribe, I will use its own name.

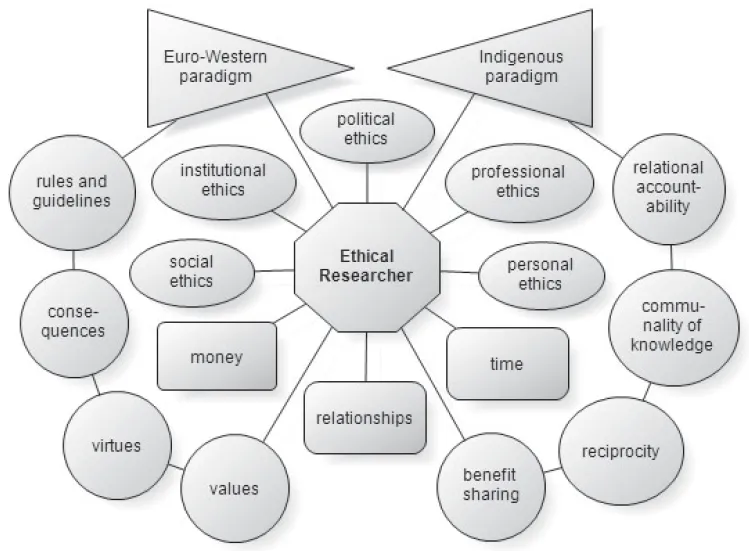

This book situates the ethical researcher at the centre of a network of connected factors that affect ethical decisions, as shown in Figure 1. Of course this diagram, like all diagrams, is an over-simplification. It would be justifiable to connect each element of the diagram with every other element, but that would make it very hard to read. Also, it is a diagram created from a Euro-Western perspective, as it has an individual researcher placed at the centre. Such a diagram created from an Indigenous perspective might look very different.

Figure 1: The ethical researcher

The following case study will show some aspects of how this can work in practice. It is the story of a Euro-Western doctoral student’s research in South Sudan, Liberia and Uganda. Although the story is quite long, I have included it in full, as it is a very useful illustration of the interactions and intersections between individual, institutional, social, professional, political and research ethics.

Case study

Rachel Ayrton’s background is in community development, where she chose to work because of her own deep-seated concerns about local and global issues of injustice and inequality. These in turn were informed by her Christian faith. Rachel wanted to work internationally, but that is hard to get into, so she started in the UK to get experience. She developed skills in working across differences within UK communities, as an outsider, fostering the values of community development such as self-determination. She learned that it was possible to facilitate something valuable happening for people without doing it for them, and that being an outsider could be helpful in that role. Some community leaders were unable to take a neutral position because they were so embedded in their communities, whereas Rachel was able to encourage without directing.

She also did a couple of short stints of grassroots volunteering overseas, but chose not to continue with that because she concluded that it was more valuable for her than for the people she had intended to help. She decided that she wouldn’t work overseas again until she had professional skills to offer, and she thought social research skills might be useful. She had developed a particular interest in sub-Saharan Africa in general and South Sudan in particular, and for her PhD she wanted to study how trust operates in post-conflict zones. She was aware of the impact of colonialism, and of her position as a white British woman. Her experience of community development work in the UK had led to a firmly held conviction that it was possible for her to do ethical research within communities in Africa by developing respectful and productive relationships, and by maintaining a continual and iterative ethical engagement with her work.

Doing this as a doctoral student, though, raised another ethical issue. Rachel had learned, from her community development work, that it was possible to do worthwhile work in communities, as an outsider, without being extractive or abusive or self-serving. However, doing research in communities for an educational qualification had the potential to confer great advantage on Rachel, raising her status massively within South Sudanese society and to some extent in UK society too. South Sudanese people value education highly, and so would be sympathetic to Rachel’s cause. This was an interesting dilemma for Rachel, which she intended to solve by ensuring, as far as she was able, that the research she did had maximum potential benefit for her participants and for wider South Sudanese society.

Rachel had done some fieldwork in South Sudan for her MSc dissertation, and had developed relationships with South Sudanese colleagues and friends. While aspects of the role of British colonisers in South Sudan were without doubt morally questionable, the South Sudanese people Rachel met had a lot of positive things to say about the British influences in their country, as well as negative things. This made Rachel feel that being British wasn’t as loaded in South Sudan as it would be in other parts of sub-Saharan Africa. Also, being an outsider seemed useful, because everyone in South Sudanese society was implicated by identity in the networks of the Second Sudanese Civil War, which had ended after 22 years in 2005. Rachel was not completely untouched by these networks, because they affected her contacts who introduced her to potential field sites and participants, but she was not implicated by her own identity.

Altogether, South Sudan seemed an obvious place for Rachel to do her doctoral fieldwork: in particular, the city of Juba. In many ways the research would have been better done by a South Sudanese researcher, but opportunities and funding for South Sudanese researchers are very scarce, while Rachel had access to a studentship for her doctoral research. Also, there was little empirical research on South Sudan, which had gained its independence in 2011, becoming the youngest country in the world. Partly for this reason, there was no formal system of research ethics governance for social research within South Sudan.

The South Sudanese people Rachel had spoken with while she was doing her MSc fieldwork were supportive of her research aspirations, stating their belief that her proposed investigation of trust would be important for peace and reconciliation in their country. She made a plan, then, with the help and approval of local people, and a commitment to come back and see it through. In the interests of fulfilling these commitments, Rachel began learning Sudanese Arabic, not because she intended to conduct her research in that language but to help her communicate with people while she was there. Her South Sudanese tutor was so supportive of her proposed work that he sometimes waived his fees when she was in financial difficulty, and took pains to teach her about South Sudanese culture and politics as well as the language.

During the first year of her PhD, Rachel had to suspend her doctoral study for a while, due to outstanding professional commitments. The day before she was due to resume her studies and begin the process of applying for ethical approval from the University of Southampton, a new civil war broke out in South Sudan, beginning with fighting in Juba. This was heartbreaking for Rachel, who was desperately worried about her friends and contacts. Initially it seemed that the conflict might be short lived and containable, but in time it became apparent that it would be a longer-lived crisis. The UK government’s Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) gave South Sudan a red rating, which meant that Rachel could not travel there, because her university could not insure her for travel to anywhere that didn’t have a green rating. She considered doing her fieldwork with South Sudanese refugees in Uganda, or with South Sudanese people in the UK, but in the end she decided to take her supervisors’ advice and choose a different country. This led to some difficult conversations with South Sudanese people, particularly her Sudanese Arabic tutor, whom Rachel did not want to disappoint.

It was also difficult for Rachel to work out where to go instead. She chose to stay in sub-Saharan Africa because she had some knowledge of the region, and looked at conflict data to help her make a shortlist of possible countries. There were also some pragmatic factors: she didn’t have time to learn another language, so she needed to choose a country that used English or French for administration, and of course it had to have a green rating from the FCO. While Rachel was doing this work, she had a stroke of luck: a good friend was able to put her in touch with a senior member of staff at the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) who agreed to facilitate contact with the national Red Cross Society in the country she chose. A formal partnership agreement was made between Southampton University and the IFRC on this basis.

The country Rachel chose was Liberia, which again had no formalised system of social research ethics governance. She designed her research, and receiving ethical approval from the University of Southampton was straightforward. She also managed to secure funding for a short orientation and planning trip to Liberia in July 2014. The Liberia National Red Cross Society was very supportive, assigning a member of staff to answer Rachel’s questions and help her as far as possible. Rachel identified two communities for her fieldwork: she met local leaders in one, and local Red Cross staff in the other, who helped her to begin to plan her fieldwork. One potential fieldwork site that was under discussion was in Lofa County in the north-west of Liberia, but Rachel and her Red Cross colleagues decided against it because a serious but apparently localised outbreak of the Ebola virus was centred on that area. By the following month the Ebola crisis had taken hold throughout the country and it became apparent, once again, that Rachel couldn’t do the fieldwork she had planned, or honour the commitments she had made to local people.

Due to extenuating circumstances, Rachel was able to negotiate an extension to her doctoral funding: technically it was a six-month extension, but as it took two months to negotiate, it was only a four-month extension in practice. The extension enabled her to make a final attempt to do fieldwork in sub-Saharan Africa, this time in northern Uganda. One of her supervisors had a former student who was now an academic in Kampala, and he was able to put Rachel in touch with another academic in the north of the country, close to the border with South Sudan. The conflict between the Ugandan government and the Lord’s Resistance Army spanned the border between northern regions of Uganda and South Sudan. One of the participants in Rachel’s MSc research had been displaced by this conflict, so she felt as though she was getting close to where she’d started. However, she didn’t have the resources to make an exploratory trip to Uganda, and it was difficult to work with people whom she hadn’t met, or to work remotely with people who usually work face to face.

Also, unlike South Sudan or Liberia, Uganda benefits from a system of research governance, and Rachel had to apply for ethical approval in Uganda. There are not many research ethics committees; there was one at the university in Kampala that Rachel could have reached with the help of her contact there, but as she planned to do her fieldwork in the north of the country, she decided it was more ethical to approach a local committee. Although the administrator there was helpful, the process was quite opaque. There was uncertainty about whether Rachel would need to go and present her research in person, which she couldn’t afford to do, because if they had asked for changes she would have had to wait another month, and she had neither the time nor the money. There was apparently a system of expedited review, but nobody could tell Rachel what the criteria were to qualify for that system. Then they said that her work could qualify if she had her materials translated into the local languages, and offered to arrange that, which she accepted; however, there were a number of delays due to difficulties in communicating by e-mail, with messages failing to arrive in both directions. As a result, Rachel’s extension was used up and so were two more months, and she reached the point where she simply didn’t have time to travel for fieldwork if she was to complete her PhD.

Ethics interactions

The story of Rachel’s attempts to do fieldwork in sub-Saharan Africa has a lot to teach us about how research ethics can interact with political, professional, social, institutional and individual ethics.

Sub-Saharan Africa is a highly politicised region, and the impact of colonisation by various countries is still strongly and widely felt. Rachel was aware of how this interacted with her plans and her work in South Sudan and Liberia. Her proposed research initially found political favour in both countries, but civil wars and health crises are political situations that cause po...