![]()

PART ONE:

RISING TO THE CHALLENGE

![]()

ONE

Evidence-based policy making and social science

Gerry Stoker and Mark Evans

There are good reasons why social science and evidence-based policy making are not always in tune with each other. The aim of this chapter is to help improve and advance the relationship between the two, but, equally, we do not want to fall into the trap of being naive about the inherently challenging character of the relationship. There are features of the way that policy processes operate and social science works that create tensions in the relationship. It is these tensions that we explore in this chapter.

Evidence provided by social science can be misused by political interests, the media can oversimplify complex research findings and, occasionally, the political leaning of the researchers may inappropriately colour the objectivity of the research or at least those parts of the results that are most widely promoted. We can also view as naive an understanding of the policy process as driven by the rational decision-making model. The policy process is not characterised by temporal neatness. The policy process only rarely follows the linear process of conceptualising the problem, designing an intervention, providing solutions and evaluating that intervention. As all the established policy making models tell us, from the multiple streams framework to punctuated-equilibrium models (for a review, see Sabatier, 2007), the policy process involves a complex set of elements that interact over time. Problems, solutions and political opportunities may all become prominent at different times. It is clear that researchers hardly ever find themselves in the position of problem-solving where there is an agreed view of a challenge and a consensus that something should be done about it. Only rarely will the conditions emerge for a pure problem-solving model: a clear and shared definition of the problem, timely and appropriate research answers, political actors willing to listen and the absence of strong opposing forces. Much more often, social scientists, like many other policy players, struggle to find the appropriate window of opportunity in which to make their impact.

Policy making is a political process and we will show how policymakers themselves view constraints on their capacity to take up and use evidence. Evidence is joined by many other factors in determining policy choices, and various system, culture, institutional and environmental factors limit the capacity of policymakers to take evidence on board. These factors can provide external barriers to the impact of evidence. In the second part of the chapter, we explore how social science has several internal barriers to delivering appropriate and valuable evidence to policymakers. Social scientists in universities, in particular, in most Western countries, have professional and career incentives to focus on research that does not have a strong applied dimension. Many academics have doubts about the normative issues thrown up by engaging with power structures and actors through policy making. Historically, social science has developed with a greater focus on providing critical commentary than on offering solutions.

Evidence on the limits to evidence

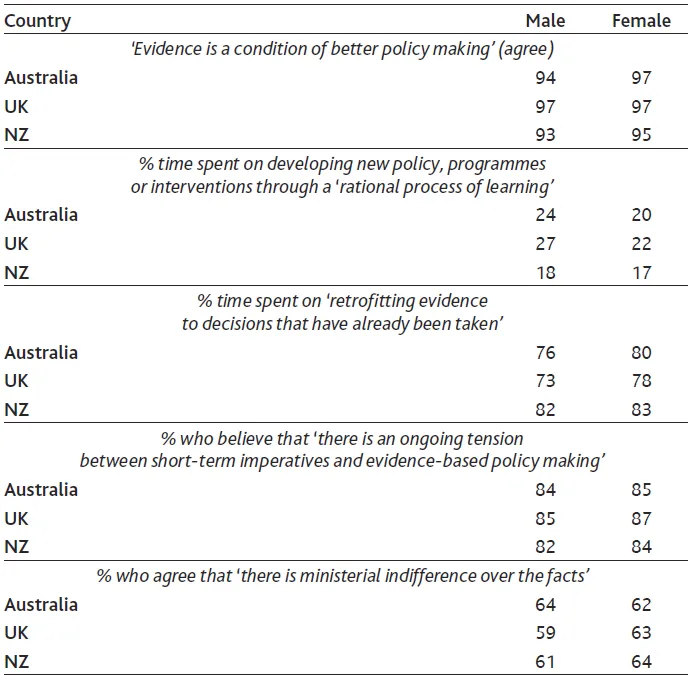

Drawing on work undertaken by one of us (Evans) derived from a series of executive workshops with senior policy officials held in Australia, the UK and New Zealand (NZ) during 2012–14, we can clearly show that while evidence is viewed as vital to policy thinking and decision-making, it can also be a luxury item used as window dressing rather than as the decisive factor in decision-making. As Table 1.1 indicates, policymakers are clear that evidence is an insufficient criterion for winning the war of ideas in a contested policy environment, and they could identify a range of barriers to evidence-based policy making and the use of high-quality policy advice.

On the issue of whether evidence is a sufficient criterion for winning the war of ideas, strong majorities recognised the importance of evidence as a necessary condition of better policy making, but the vast majority identified an ongoing tension between short-term imperatives of governing and evidence-based policy making, combined with ‘ministerial indifference over the facts’ as a constraint. Rather than the evidence steering policy, public officials argued that they spent most of their time retrofitting evidence to support decisions that had already been taken – what can be termed ‘policy-based evidence-making’ (Evans and Edwards, 2011).

There were some differences in attitudes among policy officials. Notably, more respondents who had been in the service for 10 years or more perceived that the use of evidence in policy making was in ‘dramatic decline’, and women were demonstrably more cynical than men. The type of department/agency also mattered. The more technical and less politicised the department, the greater the focus on evidence-based policy making. It is also important to note the general perception that austerity, particularly in the UK and NZ, was driving out evidence-based policy making. In both cases, large-scale retrenchment appears to have had short-term impacts on strategic policy capability, such as the loss of specialist expertise and institutional memory. Subsequently, a range of interventions were introduced in both countries to address these issues.

Table 1.1: Evidence on the non-use of evidence from public officials

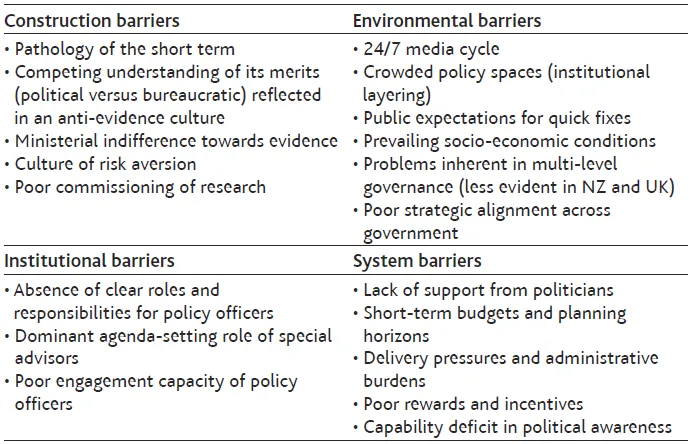

In more detailed deliberations, the policymakers identified a range of barriers to the use of evidence in policy making. We organised these responses (see Table 1.2) around four sets of constraints: ‘construction’ barriers refer to how evidence-based policy making is perceived and practised; ‘environmental’ barriers are those barriers that are outside the control of policy officers but impact directly on their work; ‘institutional’ barriers capture the impact of organisation structures, resources and roles that can block the use of evidence; and ‘system’ barriers refer to norms, rules and processes embedded in governance that inhibit evidence-based policy making.

Table 1.2: Barriers to the use of evidence identified by public officials

The electoral and 24/7 media cycles have created a strong pathology for fast thinking – ‘off the shelf’ solutions to policy problems. Evidence-based policy making is associated with slow thinking processes that cannot be immediately integrated into decision-making processes at a time when politicians are looking for quick, high-impact fixes to the problems they are facing. At a bare minimum, there does appear to be some ministerial and political indifference towards evidence (although there are always exceptions to this rule), and where social scientists are deployed in problem-solving processes, their engagement tends to be driven through interpersonal relationships with policymakers. There is also mounting evidence that special political advisors play a key agenda-setting role in Westminster systems, particularly in Australia and the UK, and tend to be champions of ‘policy-based evidence-making’ (see Eichbaum and Shaw, 2007, 2008, 2011; Tiernan, 2007; Gains and Stoker, 2011; Boston, 2012; Rhodes and Tiernan, 2014). Paradoxically, these perceptions tend to be equated with notions of risk aversion, when the case for evidence-based policy making would appear strongest as the risk of failure is greatest. What is certain is that ministers have a greater range of sources of policy advice than ever before and social scientists (as well as internal policy officers) need to understand that they are engaged in a war of ideas.

The construction barriers are in some ways the greatest stumbling block to the use of evidence, but as Table 1.2 shows, policymakers could also identify a range of environmental, institutional and system barriers to the use of evidence. There are more environmental pressures that push for not using evidence than push for using it. There are institutional factors that limit the capacity to use evidence. The wider system has many constraints set against evidence use. It would appear, then, that there are many obstacles in the policy world that make it less than a hospitable world for academic research findings. As Carol Weiss (1979: 431) remarks:

There has been much glib rhetoric about the vast benefits that social science can offer if only policymakers paid attention. Perhaps it is time for social scientists to pay attention to the imperatives of policy-making systems and to consider soberly what they can do, not necessarily to increase the use of research, but to improve the contribution that research makes to the wisdom of social policy.

Understanding and challenging the barriers to evidence

It is important to recognise that the barriers to the use of evidence are not driven by the wilful ignorance of policymakers; rather, they are a reflection of their world. The ‘listening but not listening policymakers’ (that is those that look at evidence but do not use it) phenomena can reflect the desire of politicians just to exercise their own choices regardless of evidence or at the behest of powerful interests, but there are other factors more often at work that reflect less the perversity of politics and more its complexity. The good news is that these factors can be ameliorated to some degree by the way that academics behave. In short, the barriers to the use of evidence cannot be addressed if those reflect a wilful determination to neglect evidence, but if they reflect the complex dynamics of a policy decision, then by understanding those dynamics better, social scientists offering evidence can have a greater impact.

A primary question for the policymaker is: why should I pay attention to this issue rather than many others? When academics enter the policy process, they naturally assume that process started when they entered, but, of course, it did not. As noted earlier, there are only limited windows of opportunity when an issue becomes sufficiently pressing to encourage a focus on it. Understanding the rhythms of policy making around manifestos, big speeches, set-piece agenda-setting opportunities around the Budget or other much more low-key developments can help with getting the timing of the intervention right. Part of the art of having an impact is being in the right place at the right time and then, of course, being able to act when the opportunity presents itself.

Policymakers will sometimes say, and often think, ‘bring me solutions not just problems’. As noted later in the chapter, there are factors in the internal construction of social science evidence that can limit its impact. Academic research is often more focused on identifying an issue of concern and its dynamics rather than focusing on potential actions or interventions (they may get mentioned in the last paragraph of a report). Explanation is plainly central to what we do, but academics could perhaps do more to take on the challenge of designing solutions. There still remains an issue in that academics often couch their arguments in terms of the limits of the evidence and policymakers might, in turn, seek a more definitive position. Again, this concern is not insurmountable and one response is for the academic to take the position of ‘honest broker’, laying out options and choices for the policymaker.

If an intervention is identified that should work, it is still subject to challenge about its administrative, financial and political feasibility. The question for policymakers is not ‘Can it be done?’, but rather ‘Can it be done by this government at this time?’. Showing that a policy response proposed is right (a solution to the identified problem) is only half that battle, if that. For the policymaker, it is not what works, but what is feasible, that matters. Can the challenges of administration, resourcing and political support and ownership be met? When academics step into the world of policy making, they should be sensitive and as informed as possible about these challenges; avoid giving the appearance of naivety, this is not a strong selling point when trying to persuade. The question for the policymaker is not simply ‘Do I support this policy?’, but rather ‘How much energy and political capital would I have to expend to make the policy win through against opposition from other sources?’. Policymakers know that there are only a limited number of things that they can realistically achieve, and they may have other more pressing priorities. Picking the policymaker both able and willing to run with a policy is by no means easy, but academics need to be aware of this factor in the policy making process and think clearly about how to make the policy appear doable.

Let us say that a cadre of policymakers buy into the idea of doing something but their enthusiasm then gets tested in the wider arena of policy making. They have to show not only that the policy will beat the problem and that it is feasible and doable, but that it can also win in response to the ‘opportunity costs’ question? The policymaker will be asked: ‘If we spend time, money and effort on this proposal what are we not going to be doing that we should have already been doing?’. Policy is a competition for time in a very time-poor environment. There are many issues and so little time; academics know that about their research activities, and so need to remember that it applies with even more force in the world of policy.

Networks matter in research, and they matter in policy making as well. It is not normal for ideas from an unknown source to be easily embraced, and this is true for many areas of life. Politicians and policymakers, in particular, have survived in their careers by being suspicious to some degree. They will always ask, in their heads at least: ‘Are you selling me a pup?’ Policy making does rely to a large extent on trust in the source and status in the network, so academics need to build both their trust and status if they want to be taken seriously. Years, or decades even, of non-engagement followed by a sudden step on to the policy stage proclaiming solutions is an unlikely formula for success.

In some ways, the point is so obvious that it is amazing how often it gets overlooked: politicians and other policymakers believe in things. They have preferences, philosophical positions (some more coherent than others) and even ideologies about what the world should be and how it should be changed, that is, both ends and means are political choices. Therefore, alongside evidence, values matter in the policy process. The ‘what works’ rhetoric can imply that choices are entirely technical but nothing could be further from reality in democratic policy making. Choice is about whether a policy matches the chooser’s desired means and goals, and understanding that is essential for all academics and democrats. Moreover, academics are not immune from having values, preferences and ideologies, and though we try to guard against their impact on our research, there is no denying that they can, especially on what we choose to research and the manner in which that research is presented.

Nothing is certain and a policy can be killed by the fear of unintended consequences. ‘The probabilities suggest …’ – the language of much scientific discourse – may not be strong enough to stop a wave of fear about unintended consequences. Academics rightly want to be clear about the limits of the evidence but they should also be keen to pre-identify and try to undermine spurious objections to their findings. Opponents of any measure tend to frame their arguments along standard lines: ‘it will not achieve the desired effect’ or, worse, ‘it will have perverse effects’ or, worse still, ‘it will jeopardise much-cherished other gains’. Understanding how interventions are going to be challenged should be something that academics should be aware of when they engage.

However, even all the aforementioned obstacles are overcome and your research does, indeed, lead to a policy intervention, it may be that implementation failures undermine it. The forces of opposition to a policy do not stop once it is adopted. In addition, ‘events, dear boy, events’ is an alleged explanation that former British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan offered as to why achieving anything in politics is so difficult. The unpredictable, sudden crisis can blow a carefully evidenced and prepared policy process of course. Just as in nature, where we are learning that changes in woods/forests, for example, are driven as much by major events as slow environmental change, so it is in politics that all that appears solid and definite can suddenly melt and become an arena of uncertainty. There are many coping strategies to deal with this phenomenon but they all boil down to: ‘if at first you don’t succeed, then try and try again’.

Academic incentive structures against engagement

Social scientists may also need to investigate the issues in their own practices and culture that restrict the engagement between social science and policy making. New career scholars know that publishing in good-quality journals is their ticket to a successful career. Making an effort to promote the relevance of their work to policymakers would seem a potentially unproductive waste of time. General theory and groundbreaking work that heads off in novel directions is valued over applied theory. Empirical work is more likely to be assessed according to the virtuosity or novelty of its methodology rather than the relevance of its topic or findings to external observers.

Writing about International Relations, but in an observation that might generally be applied to the social sciences, Walt (2005: 38) argues that ‘[t]he discipline has tended to valorise highly specialized research (as opposed to teaching or public service) because that is what most members of the field want to do’. There are not many academics that spend much time in the world of government or policy advice and the numbers that have taken up the opportunity in recent years has probably declined. Even in the US, where an extensive system of appointments gives greater scope for scholars to move from academia to government and vice versa, the tendency has been for the traffic to diminish. As Nye (2008: 594) comments:

The United States has a tradition of political appointments that is amenable to ‘in and out’ circulation between government and academia. While a number of important American scholars such as Henry Kissinger and Zbigniew Brzezinski have entered high-level foreign policy positions in the past, that path has tended to become a one-way street. Not many top-ranked scholars are curre...