eBook - ePub

Managing Community Practice

Principles, Policies and Programmes

- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Managing Community Practice

Principles, Policies and Programmes

About this book

0

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

THREE

Organisational management for community practice: a framework

Introduction

The central challenge of this chapter is simply stated: what management systems and what organisational structures will best enhance the work of community practitioners, enabling them to maximise their effectiveness in supporting communities to take action? Too often, there is an assumption that there is ‘one best way’ to manage work organisations. This chapter represents a plea for ‘organisational alignment’, so that work practices of community practitioners are supported by appropriate, customised organisational and managerial contexts.

This chapter is in four parts. It begins with a brief overview and critique of ‘one best way’ thinking about organisation and management. Building on the discussion of the nature of community practice in Chapter One – on how the power and goals of a wide variety of institutions and practitioners interact to create the complex field of community practice – the chapter goes on to identify a number of key features of community practice as a work process that should influence its organisation and management. This leads to the presentation of a simplified operational model – comprising organisational structure, culture, systems and procedures – required to support such work. Finally, the chapter considers aspects of managerial roles and management styles that, pursued within the context of this organisational model, will best promote effective, high-quality practice.

This chapter, in short, offers frameworks for thinking about and modelling organisation and management for community practice. Such frameworks and models need to be carefully selected and adapted, taking into account the goals and constitution of particular employing organisations, the kind of community practice implemented, and the nature of the geographical and cultural context in which the work is undertaken. It would, indeed, be ironic if the frameworks and models discussed here were to be construed as prescriptions for ‘the one best way’.

‘One best way’?

It is now over a century since Frederick Taylor (1911), prototype management guru and early advocate of ‘scientific management’, first proclaimed that it was possible to discover the fundamental and immutable principles of organisational management. ‘Mechanistic’ models of management should, according to Taylor, mirror the forms of mechanised (motor car assembly line) mass production being pioneered by his friend Henry Ford. Standardised working practices, top-down job design, strict coordination and control through hierarchical layers of management and supervision, and disciplined compliance to rules and regulation increasingly became accepted dictums of much 20th-century industrial and commercial management.

The idea that there is ‘one best way’ to design and manage work organisations continues to cast its long and baleful shadow over much organisational theory and practice. As Morgan (2006, p 31, emphasis in original) notes:

Classical management theory and scientific management were each pioneered and sold to managers as the one best way to organise. The early theorists believed they had discovered the principle of organisation which, if followed, would more or less solve managerial problems forever. Now we only have to look at the contemporary organisation scene to find that they were completely wrong on this score. Indeed, we find that their management principles often lie at the root of many modern organisational problems.

In seeking models for the organisational management of community practice, we certainly need to look beyond Taylorist thinking. Post-Taylorist thought has emphasised that organisational design and management practice needs to recognise that ‘one best way’ thinking is inadequate because:

- The nature of most organisational work is no longer (if it ever was) akin to assembly-line car production. As Morgan (2006, p 27) notes: ‘Mechanistic approaches to organisation work well under conditions when machines work well, but in more and more work situations machine-like management and organisation is massively dysfunctional’. The work process of the community practitioner is about as far away as you can get from that of the worker on the assembly line.

- Managers are now acutely aware that they need to be able to adapt their organisations to the particular (and changing) contexts and environments in which they operate. Social, economic and cultural change is ubiquitous and, as we argue in Chapter Four, organisations need to maximise their capacity for adaptability and change and to become ‘learning organisations’. Community practice has, historically, been deployed to support a wide variety of evolving social and political goals and programmes (Butcher, 1993; Somerville, 2011) and there is no reason to believe that this will not continue to be the case.

- Following from the previous points, organisations – including those responsible for supporting community practitioners – need to be seen as more akin to ‘organisms’ than machines. The organic image prompts us to think in terms of open systems (rather than in closed structural terms), of interaction with (and reciprocal adaptation to) changing environmental contexts, and of growth and evolution.

Community practice as work process: the ‘5P + C’ model

So, what are the key features of community practice as a work process and what implications – for organising and managing such work processes – follow from this? It may be useful to approach these questions through use of a particular model of community practice. This involves us asking, first of all, how can we best characterise the Purposes, Policies, Programmes, Practices and Processes of community practice (the ‘5Ps’), and the operating contexts of that practice (‘C’)? I will call this the ‘5P + C’ model. We can then go on to ask: what do such characteristics imply for the organisation and management of the practitioners responsible for undertaking such work?

Briefly, the elements in the model may be described as follows:

- Purposes: these are the broad overall intentions of the work, incorporating the aims, the underlying principles and values, and the macro-objectives of the work. For example, the intention of working towards a more socially inclusive society, based on values of equality and community, may be seen as a guiding purpose behind much community practice.

- Policies: the specific, mandated frameworks for action that community practitioners are employed to pursue in particular organisations at particular times. For example, a government may promote a strategy for neighbourhood renewal, thus providing a policy framework and context for a particular form of community practice.

- Programmes: the specific plans of action through which community practitioners seek to implement policy. For example, a local authority may pursue a policy of area decentralisation and local democracy – with community practitioners employed to support a programme designed to establish and support a system of area forums.

- Practices: the general working methods and operations, underpinned by associated skills, that are used by community practitioners, for example: networking, group work, action research and so on. Many such practices are characteristic of a variety of other human service occupations of course, and are not specific to community practice.

- Processes: the routine series of practices and operations that coalesce in ways that do characterise community practice as an occupation; for example, community capacity-building is seen as a characteristic work process of some community practitioners.

- Contexts: the operating and socio-political environment in which the community practitioner is employed, for example: inner-city or rural community; locality community or interest community.

With these distinctions in mind, we can begin to look in a little more depth at the realities of the community practitioner’s occupational role and remit under each of these headings.

Purposes

Active community

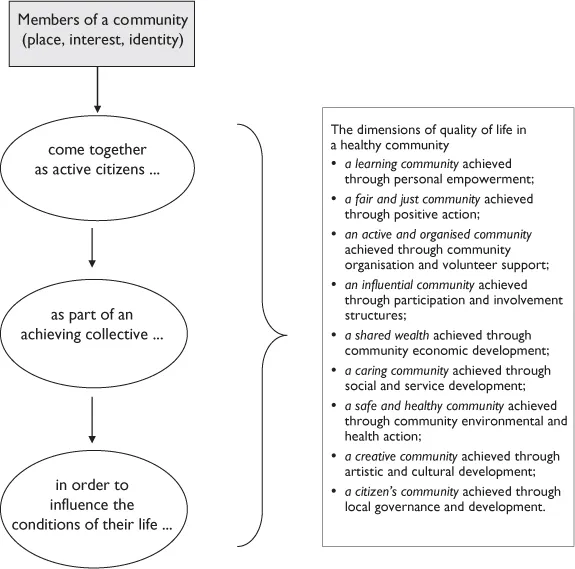

The contemporary purposes of community practice are presented schematically in Figure 3.1. At the very centre of the diagram – the ‘bullseye’ – we identify ‘generating and supporting active community’ as a key purpose of community practitioners. This was stressed in Chapter One (p 11). Whether working with locality, interest or identity communities, the community practitioner’s aim is to support members of communities in developing the motivations and dispositions, skills and knowledge, to work to achieve their common goals. Alan Barr has conducted research among community practitioners and community activists into the characteristics that help define, for community members, ‘quality of life’ in the community (see Chapter Eight, this volume, p 176). Figure 3.2 draws on the research of Barr to link ‘quality of life measures’ to the idea of ‘active community’.

Figure 3.1: Community practice: purposes

Figure 3.2: Active community: processes and outcome

Sources: See Alan Barr et al (1996) and Chapter Eight, this volume.

Active citizenship

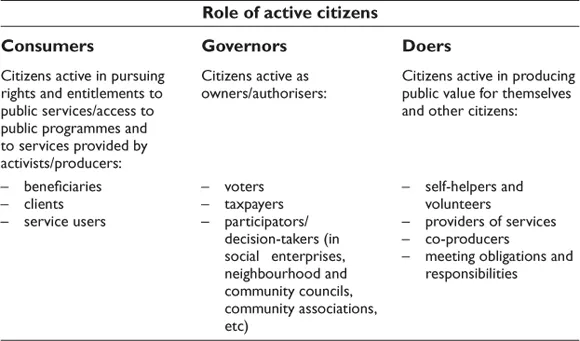

The concept of active community presupposes an enlarged role for the citizen in society – represented by the middle ring in Figure 3.1. Community practice embraces a movement away from narrow ideas of citizenship – as concerned predominantly with rights to use or consume state services on the one hand, and cast a vote for someone to represent their views within the polity on the other. Goss (2001) and Benington and Moore (2011), following Moore (1996, 1999), usefully conceptualise an enlarged view of active citizenship – one in which the citizen embraces both a range of public deliberation and decision-taking roles (in addition to voting every four or five years) as well as engaging in a range of types of collective action to produce (as well as consume) public value (see Table 3.1).

Table 3.1: Community practice: active citizenship

Source: Adapted from Moore (1999) and Goss (2001)

Public ‘end-state’ purposes

The previous two purposes of active community and active citizenship complement and underpin a third set of purposes (the five oute...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of figures, tables and boxes

- Preface to the second edition

- Acknowledgements

- Notes on contributors

- Introduction

- one What is community practice?

- two The historical and policy context: setting the scene for current debates

- three Organisational management for community practice: a framework

- four Individual and organisational development for community practice: an experiential learning approach

- five Negotiating values, power and responsibility: ethical challenges for managers

- six Linking partnerships and networks

- seven The manager’s role in community-led research

- eight Participative planning and evaluation skills

- nine Conclusion: sustaining community practice for the future

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Managing Community Practice by Banks, Sarah,Butcher, Hugh L,Sarah Banks,Hugh L Butcher,Andrew Orton,Jim Robertson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Work. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.