eBook - ePub

The Essential Guide to Planning Law

Decision-Making and Practice in the UK

- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Essential Guide to Planning Law

Decision-Making and Practice in the UK

About this book

This comprehensive yet concise textbook is the first to provide a focused, subject specific guide to planning practice and law. Giving students essential background and contextual information to planning's statutory basis, the information is supported by practical and applied discussion to help students understand planning in the real world. The book is written in an accessible style, enabling students with little or no planning law knowledge to engage in the subject and develop the necessary level of understanding required for both professionally accredited and non-accredited courses in built environment subjects. The book will be of value to students on a range of built environment courses, particularly urban planning, architecture, environmental management and property-related programmes, as well as law and practice-orientated modules.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Essential Guide to Planning Law by Adam Sheppard,Deborah Peel,Heather Ritchie,Sophie Berry,Sheppard, Adam,Peel, Deborah in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Environmental Law. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Edition

1Subtopic

Environmental LawFOUR

Planning, plans and policy in the devolved UK

Chapter contents

• The current legislative contexts

• Plan-led systems

• National, regional and strategic plans and policy

• Local development plans

• City-regions, metropolitan areas and ‘above-local’ scale planning

• Neighbourhood plans in England

• Marine plans

• Chapter summary

Introduction

This chapter explores in greater detail the legislative context in place at the time of writing (July 2016) and outlines how planning is organised across the devolved UK. We consider the various systems and structures of government and plans in place for designing and implementing planning regulations, again noting that planning is a dynamic field and liable to change. In addition to the legislation, we highlight the importance of understanding the various institutional arrangements to support development planning and the roles played by national policy and territorial planning and by local policy in guiding, shaping and managing change. We also consider the emerging framework for marine planning, which is related to and draws on terrestrial experience.

As in the previous chapter, across the UK a plan-led system is in place, meaning that plans and policy ‘lead’ (or direct) decision-making within a discretionary decision-taking context. The purpose of a plan is ultimately to enable something to happen in a particular way, or in such a manner as to derive a particular benefit. As such, plans variously protect, conserve, manage, enable, deliver and support land and property development. The specific arrangements for development planning differ in practice in England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland, reflecting the different local government arrangements in operation and different approaches to planning and the distribution of power and decision-making. We now consider the planning law frameworks of the four administrations. The discussion is organised in relation to primary and secondary legislation, regional-wide (territorial) planning policy and guidance, and operational aspects. Given our focus on development management, we pay particular attention to contextualising the geography of local government

The current legislative contexts

England and Wales

It is appropriate to consider England and Wales together because, from the legislative perspective, they have been very closely aligned until recently, when some divergence has become evident.

Primary legislation

The primary legislative frameworks for the planning systems in England and Wales are broadly the same (Cave et al, 2013). The main planning acts in force are: the Town and Country Planning Act 1990; the Planning and Compulsory Purchase Act 2004; the Planning Act 2008; the Localism Act 2011 and the Planning and Housing Act 2016 (both of which apply only in England); and the Planning (Wales) Act 2016.

In England, the Localism Act 2011 provides neighbourhood planning powers and a duty for cooperation between authorities. The move towards localism in England is intended to give communities more autonomy and responsibility to address the needs and wants in their specific area, the scope of which would not necessarily be identified by central government or councils governing the wider district in which a community is located. Wales does not have an equivalent Act to this, but on-going discussions concerning local government include the role and potential of the neighbourhood scale of planning; reform is likely, and, with this, it is likely that greater autonomy and responsibility will come.

Where parts of the Planning and Compulsory Purchase Act 2004 and Planning Act 2008 are not in force in Wales, the Welsh Government has the option to commence these if its want the provisions to apply to Wales. For example, in June 2015, Part 4 of the Planning and Compulsory Purchase Act was commenced in Wales to apply Sections 171E to H of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 as it applies to Wales to enable Welsh LPAs to serve temporary stop notices in respect of unauthorised development. This legislation has been in force in England since 2005.

Secondary legislation

The main pieces of secondary legislation related to planning are those governing permitted development rights and the operation of the development management system. There are differences here between the English and Welsh systems as different Orders, or different versions of them, are in force. Secondary legislation associated with other aspects of the planning system, for example regulations in respect of advertisements, rules for planning appeal procedures and fees for planning applications, also exist.

For England, particularly significant secondary legislation includes (not an exhaustive list):

• the Town and Country Planning (General Permitted Development) Order 2015

• the Town and Country Planning (Development Management Procedure) (England) Order 2015

• Neighbourhood Planning (General) Regulations 2012 (as amended)

• the Town and Country Planning (Use Classes) Order 1987 (as amended).

For Wales, the particularly significant secondary planning legislation includes (not an exhaustive list):

• the Town and Country Planning (General Permitted Development) Order 1995 (as amended)

• the Town and Country Planning (Development Management Procedure) (Wales) Order 2012;

• the Town and Country Planning (Use Classes) Order 1987 (as amended).

The array of secondary legislation in force in England and Wales, and differences between them, can sometimes make deciphering planning legislation difficult – not just for the lay person, but also for planning professionals. Moreover, various updates have been made to secondary legislation over the years. In the absence of a consolidated version of these changes it is easy to become confused and frustrated as to what is actually the prevailing legislation at a particular time. The lesson here is that one cannot always assume that the content of a legislative document found through an internet search is the most recent legal position, or even any longer in force, if ever enacted. Consolidated versions of Orders that have been in force for many years, and updated regularly, would make life much easier for everyone who wants to avoid falling foul of the legislation. The Town and Country Planning (General Permitted Development) Order 1995 is a prime example of this. For example in Wales this Order remains in force despite several updates, in recent years these include changes in relation to renewable energy generation The Town and Country Planning (General Permitted Development) (Amendment) (Wales) (No.2) Order 2012, householder permitted development rights The Town and Country Planning (General Permitted Development) (Amendment) (Wales) Order 2013 and non-domestic permitted development rights The Town and Country Planning (General Permitted Development) (Amendment) (Wales) Order 2014 all under different amendment orders, whilst permitted development rights in England are also similarly convoluted with recent amendments included in the Town and Country Planning (General Permitted Development) (England) Order 2016.

Operation of the planning system

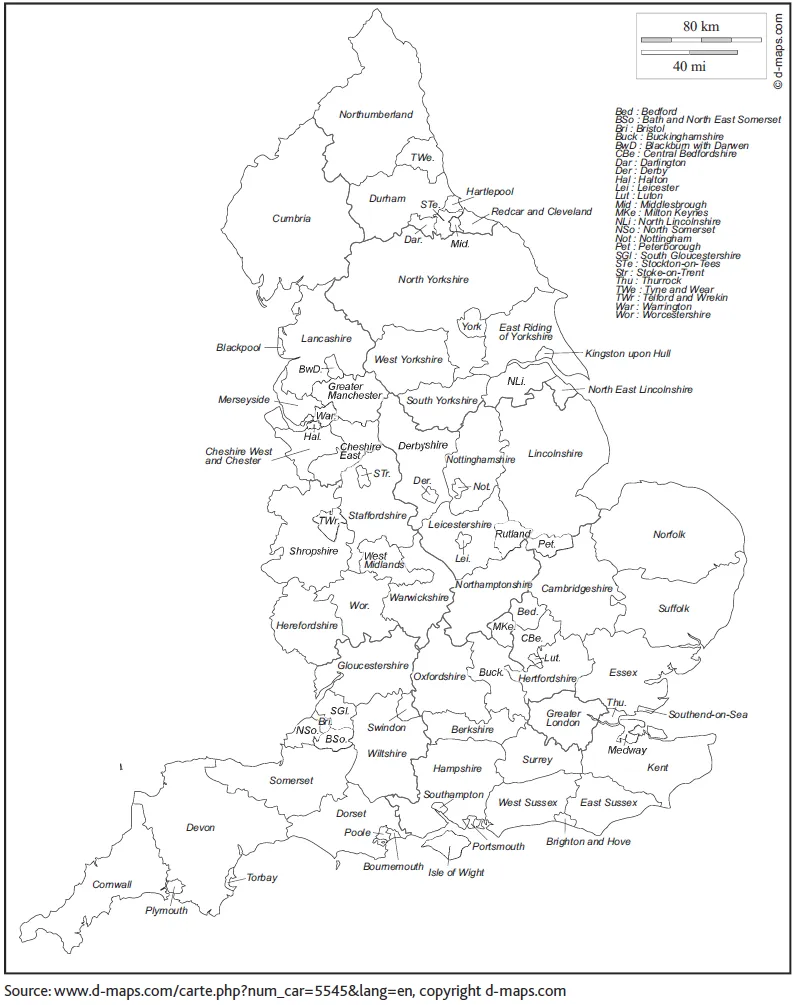

In England the structure of local government is as varied as it is complex. In some areas there are three tiers of local government: county councils; district/borough/city councils, and parish/town councils (DCLG, 2015a). Map 4.1 shows the local government boundaries for England. County councils have strategic responsibilities in relation to town planning, and determine applications for transport, minerals and waste, as well as development on their own land, for example schools. This responsibility also translates to enforcement powers in respect of these matters.

Reflecting the principle that planning is best dealt with at the local scale, most planning takes place at district level. Local councils are thus responsible for preparing local plans, determining planning applications and enforcement. Parish or town councils also have a role to play at the very local scale. In London, despite the boroughs being unitary authorities, in most respects the Greater London Authority performs a strategic-wide role and sits above this level, holding significant powers in areas such as transport and planning. Areas that include such designations as a National Park have a National Park Authority to oversee many functions and responsibilities. Some structural variations exist elsewhere, in response to devolution of powers and partnerships at the sub-regional scale. Given the increasing emphasis on the metropolitan scale, Manchester is a good example of the scaling-up of planning, since the Greater Manchester Combined Authority comprises 10 local authorities brought together to form a statutory combined authority.

The May 2016 Queen’s Speech, setting out the proposed legislative programme for government for Westminster, included a new Neighbourhood Planning and Infrastructure Bill, specifically targeting economic recovery, housing provision and infrastructure, as well as addressing aspects of resourcing neighbourhood planning to further empower local people. This Bill heralds further changes to the planning system, including, potentially, a reduction in the use of pre-commencement planning conditions.

Before the Localism Act 2011, the role of parish and town councils in the planning system in England was to comment on planning applications. In addition to this function, they now have power to make Neighbourhood Development Plans to form part of the development plan alongside the local plan for the area, and also to make Neighbourhood Development Orders (NDOs), which can grant permission for certain developments without the need to apply for planning permission. These aspects of planning law are discussed further in Chapter Six.

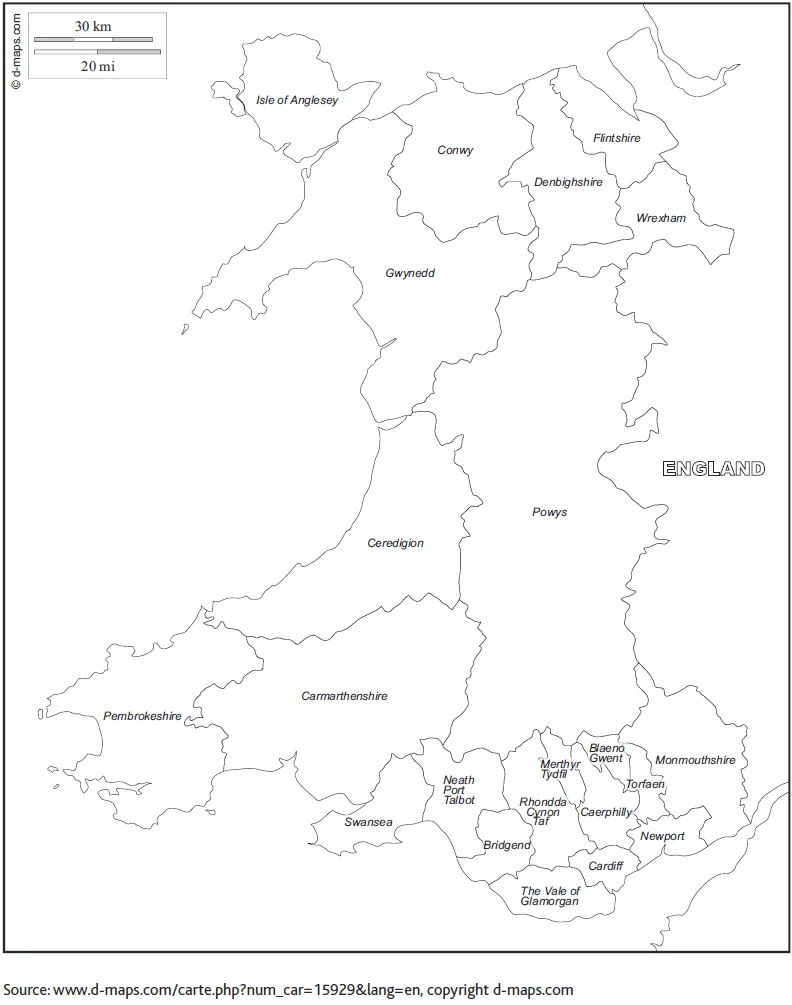

In Wales, matters may be regarded as far simpler; only a unitary authority structure exists, with community councils operating at the community scale. The responsibility for planning functions in Wales is through its 25 planning authorities, comprising 22 local authorities and three National Park Authorities. From a statutory land-use planning perspective, these authorities develop local plans and policy, determine planning applications and are responsible for enforcement of planning control.

Map 4.1: Local Government in England

The local government structure in Wales has been under review, and it is possible that the number of authorities will be reduced through merging existing authorities driven by a desire for increased efficiency of resources and improving public service. Finally, community councils are also found throughout Wales but do not have plan-making powers. Map 4.2 shows the present boundaries of the 22 local authorities in Wales.

Map 4.2: Local Government in Wales

Scotland

Primary legislation

The legislative framework for the planning system in Scotland is set out under the Town and Country Planning (Scotland) Act 1997, which was substantially amended by the Planning etc. (Scotland) Act 2006.

Secondary legislation

There exist a range of secondary legislative orders and regulations within the Scottish planning system, including:

• the Town and Country Planning (General Permitted Development) (Scotland) Order 1992 (as amended)

• the Town and Country Planning (Use Classes) (Scotland) Order 1997

• the Town and Country Planning (Development Management Procedure) (Scotland) Regulations 2008.

Operation of the planning system

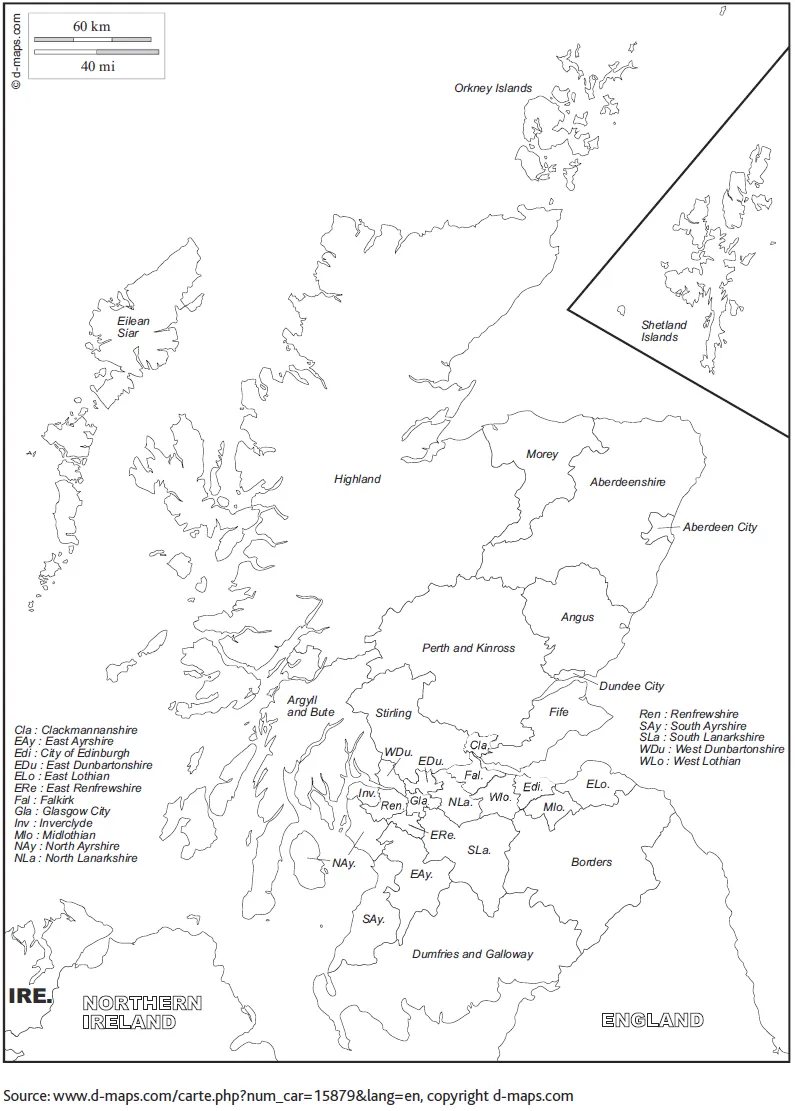

As noted in Chapter One, Scotland has a hierarchical planning system. The local planning system, including the making of local plans, development management and enforcement, is operated through 32 local authorities (Map 4.3). There are two National Parks in Scotland, although their specific planning arrangements are different from other local authorities. Scotland also has four Strategic Development Planning Authorities (SDPAs). Introduced under the Planning etc. (Scotland) Act 2006, SDPAs (similar to the example of Manchester in England) are intended to provide a strategic and cross-jurisdictional perspective. In practice, groups of LPAs work together to produce Strategic Development Plans for sustainable economic growth in Scotland’s four largest city-regions. They presently comprise: Aberdeen City and Shire; Glasgow and the Clyde Valley (Clydeplan); Edinburgh and South East Scotland (SES Plan); and Dundee, Perth, Angus and North Fife (TayPlan).

A root-and-branch review of the Scottish planning system in 2016 identified the strategic layer as requiring potential improvement, so the precise form and remit of the strategic scale of plan making may change. In contrast, and linked to wider reforms taking place in Scotland with respect to integrated public service delivery (community planning), the Independent Review of the Scottish Planning System (Beveridge et al, 2016) also recommended that there was scope for the emerging locality plans to be given statutory status by forming part of the local development plan. This line of thinking is predicated on active community engagement. Moreover, the findings of the Independent Review suggest that acquiring statutory status would only occur where it can be demonstrated that locality plans play a ‘positive role’ in delivering development requirements. In the light of neighbourhood planning experience in England, this thinking indicates a clear motivation to link communities more directly with development planning and reiterates a concern with scale. Legislative change is imminent. In its 2016 Programme for Government, the Scottish Government announced a Planning Bill early in the Parliamentary session with the stated aim of producing a high-performing planning system intended to enable housing and infrastructure delivery and promote quality of place, quality of life and the public interest.

Map 4.3: Local Government in Scotland

Northern Ireland

Primary legislation

In Northern Ireland planning law has developed differently and has followed a different time-line. Until recently, the Planning (Northern Ireland) Order 1991 was the main legislation for controlling development. In contrast to the emphasis on local government decision-taking powers elsewhere in the UK, and with the exception of legislative powers, all planning powers rested with the (former) Department of the Environment (DOE), a central government department. Following a sustained period of legislative change, a fundamental restructuring and rescaling of government arrangements the Planning Act (Northern Ireland) 2011 now provides the primary legislation.

Secondary legislation

A raft of new subordinate legislation has been made under the 2011 Act to provide the detail for the new primary legislation. Some of the main pieces include:

• the Planning (General Permitted Development) Order (Northern Ireland) 2015

• the Planning (General Development Procedure) Order (Northern Ireland) 2015

• the Planning (Use Classes Order) Northern Ireland 2015

• the Planning (Local Development Plan) Regulatio...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of figures, maps and tables

- List of boxes

- Author biographies

- List of acronyms

- Acknowledgements

- Foreword

- ONE: Planning law in context

- TWO: The nature of planning law

- THREE: The development of planning law

- FOUR: Planning, plans and policy in the devolved UK

- FIVE: Core elements of planning law

- SIX: Development management: permissions, applications and permitted development

- SEVEN: Planning conditions, agreements and obligations

- EIGHT: Specialist planning arrangements

- NINE: Other forms of planning control and consent

- TEN: Enforcement

- ELEVEN: Planning appeals, Judicial Review and the Ombudsman

- TWELVE: Reflections on planning law

- References