![]()

Part One

Empathy Level Zero: hurting

If we could read the secret history of our enemies, we would find in each man’s life a sorrow and a suffering enough to disarm all hostility.

(Henry Wadsworth Longfellow)1

![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Crime and unhappiness

Crime and the rule of law

Laws are rules created by judges or parliament to enable society to function. Originally, the law was probably little more than custom, which was then codified and issued by kings; in fact, the earliest decipherable writing of any length was a code of law (the Code of Hammurabi, a Babylonian tablet with text outlining 282 laws, dates back to about 1772 BC).2 There are rules backed up by law everywhere around us. This is generally a good thing, for example, ensuring that we stop at traffic lights and avoid smoking in enclosed public places and on railway platforms. There is usually an assumption that laws are necessary, fair and just, which matches reality 90% of the time – but perhaps not entirely. Crime is a relative rather than an absolute concept, which is defined by a society and changes over time. Homosexuality was a crime in the UK until 1967 and remains an offence in 76 countries around the world (five of which punish homosexual acts with the death penalty),3 while non-consensual sex within marriage did not constitute rape until 1991. Drug legislation fails to encompass alcohol, which is the most dangerous intoxicant of all, and the only one that is regularly related to violent crime (if alcohol were to be invented tomorrow and imported from South America, it would instantly become a Class A drug). For all its faults, the rule of law is a guarantee that wrongdoing will be addressed in a way that is independent and outside of ourselves as individuals, and this code is what makes society possible. We realise its merits if we consider what would happen if it wasn’t there.

There are a bewildering number of laws that permeate every aspect of our lives – the Labour government famously broke the record by introducing 3,506 new laws during its last year in office (2010)4 – covering everything from the legal obligations of employing a nanny to the ownership of washed-up whales (they belong to the sovereign). This book will focus on behaviour that is both unlawful and leads to someone being directly harmed as a result, recognising that ‘crime’ and ‘harm’ are not always synonymous, and there are crimes (like driving without a licence or smoking cannabis) where it isn’t possible to name an individual who has been harmed. While acknowledging that white-collar and corporate crimes also harm individuals and warrant a restorative approach, the book addresses offences committed more directly against the person, such as domestic burglary and assault.5 It accepts the need to debate and criticise our current laws and legal system, but the emphasis here is on how society deals with those who break that law.

Why do people commit crime?

Decisions we make in life are the product of a myriad of factors, past and present, all of which lead us towards making a particular choice in any given moment. Consider the last time you bought margarine. Reaching for that particular brand on the shop shelf might have been carefully planned to meet a particular need, or could have been an impulsive act – you happened to see it prominently on display and took it without thinking. You may have gone for the cheapest or the most expensive, the tastiest or the healthiest option, dependent perhaps on how much cash you had on you. Your mood, living circumstances, previous choices, gender, age, background, habits or influences from childhood could all have been factors; that is, your choice will have been dependent upon what happened in the minutes, days, months and years before you arrived at the margarine display. Perhaps, if you weren’t shopping alone, the people you were with persuaded you to follow their advice on which brand to choose. Maybe you were simply doing what you were told by your parents, flatmates or partner, or whoever it was who wrote ‘Make sure it’s Flora’ on the shopping list. Your choice in that moment might have been premeditated, targeted, impulsive or random – or the only option available to you on the shelf. Margarine manufacturers and supermarkets invest heavily in researching the complex reasons behind your choice.

It’s a big leap from choosing margarine to committing crime, but the example does demonstrate how even our smallest choices are dictated by context, circumstance, personality and environment. Similarly, there are many reasons that lead people to commit crime. Each criminal event is unique and results from a complex array of issues, as depicted in Figure 1.1.6 People who commit crimes are often able to identify these factors themselves (see Figure 1.2).

The Italian criminologist Cesare Lombroso (1835–1909) famously (and incorrectly) concluded that skull measurements provided evidence of genetic criminality. Since then, criminologists have written and theorised at length about the origins of criminal activity, citing, for example, weak social bonds (social control theory), socio-economic pressures (strain theory), structural inequality (conflict theory), geographical factors (the Chicago School) and learned behaviour from criminal subcultures (differential association theory), adding in factors to do with race, ethnicity and cultural marginalisation. Some even argue that we are all potential criminals but that moral choices stop us from committing crime.

Figure 1.1: Analysis of factors and pathways contributing to criminal events and behaviours

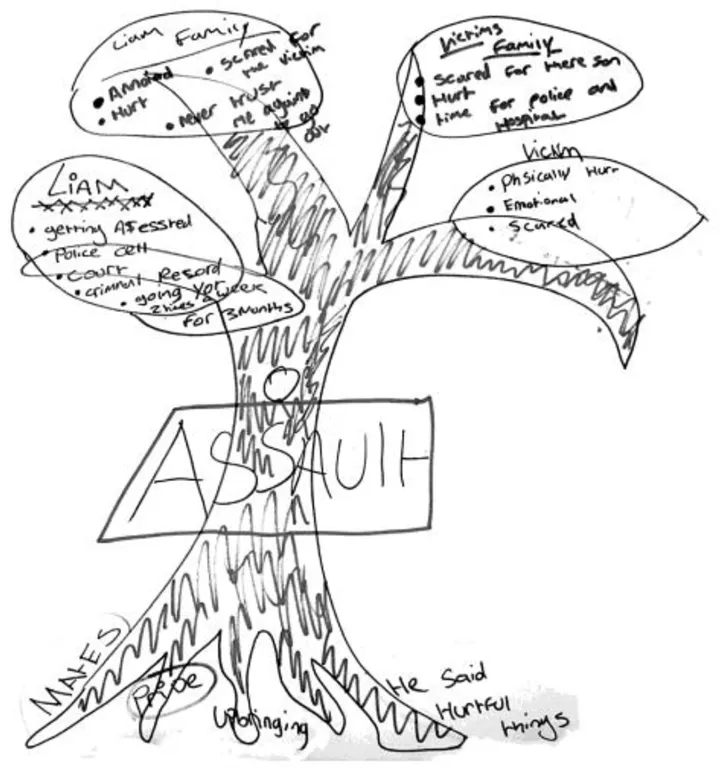

Figure 1.2: The conflict tree

Note: During a victim empathy course, Liam reflects on the factors that led to his crime. These include: Past factors (‘upbringing’); External influences and peer pressure (‘mates’); Circumstances immediately preceding and triggering the crime (‘He said hurtful things’); and Internal factors (‘pride’). The leaves are his reflections on the consequences of his behaviour

Source: Reproduced with kind permission from Wallis, P., Aldington, C. and Liebmann, M. (2010) What have I done? A victim empathy programme for young people, London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Against this complexity, Bo Lozoff7 asserted boldly during a talk I attended in 1994 that ‘All crime arises from unhappiness’. It is a sweeping statement that, like most generalisations, doesn’t completely hold up to scrutiny. Many crimes relate to unhappiness only in the most tangential way (although a rival theory that relates crime to high rather than low self-esteem has been refuted through research).8 Greed motivates many perpetrators, particularly in white-collar crimes, and prejudice, contempt for others and alcohol (which can facilitate crime) may all be causative factors. It is also wrong to suggest that everyone committing a crime is the victim of circumstances beyond their control, and therefore bear no moral responsibility for their acts. With all these caveats, there is still a grain of truth in Bo’s comment. People who commit crime often (not always) have a well of unhappiness arising from unresolved lack, loss, rejection or abuse, although many will not have consciously acknowledged this.

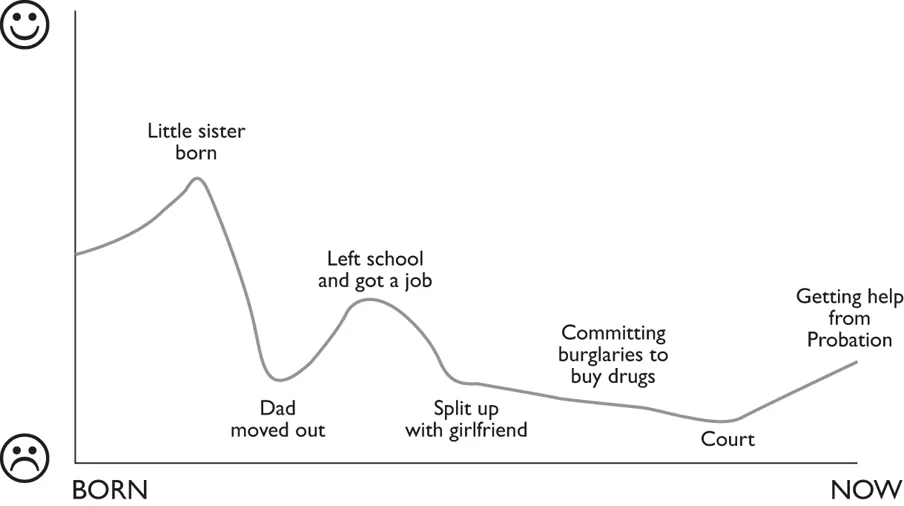

In the 1990s, I helped facilitate a groupwork programme for men on probation who had been convicted of ‘joyriding’ – a crime not immediately associated with unhappiness. Participants were invited to draw a ‘life graph’, where the horizontal axis went from birth to the present and the vertical axis from deeply unhappy at the bottom to ecstatically happy at the top (see Figure 1.3). The example drawn on the flipchart showed typical ups (getting a new job, having a baby) and downs (losing someone special, breaking up with a partner), with an average state of happiness somewhere in the middle. I recall one group where the young men (without looking at one another’s graphs) all crammed their lines and lives in the inch or so beneath the bottom axis – presumably feeling that their lives all belonged in a zone below deep unhappiness. Moreover, without any prompting, they all identified a negative life event immediately preceding their offence. This confirms research which shows that crime often follows loss, which was certainly true for this group. One study of 200 young offenders found that 57% had experienced bereavement or traumatic loss.9 Unresolved grief is a significant risk factor for turning young people to offending.

Figure 1.3: An example of a life graph

When crime arises from a place of unhappiness, it is sometimes possible to trace its origin to an earlier experience of victimisation – often far back in childhood. Some families seem caught in a cycle of crime that goes back generations, and for many, episodes of committing crime are punctuated by experiences of being victimised. One study found that 50% of young people who had committed an offence in the previous 12 months had also been the victim of a personal crime in the same period, compared with 19% of those who had not committed an offence,10 while in another study, more than two thirds of serious young offenders disclosed childhood abuse.11 Speaking out in 2002 against a tide of political rhetoric about being ‘tough on crime’, Sir David Ramsbotham said of young people in custody:

Cartoon 1.1: Breaking the cycle

Most have grown up in impoverished circumstances in socially deprived areas within chaotic, struggling families; many have had damaging periods in local authority care, many have been badly let down by the education system, many have faced racial and other forms of discrimination, many have been physically and sexually abused. Anyone who has worked with these children knows the painful truth … and that those who portray young offenders as clever immoral thugs taking advantage of a soft system could not be wider off the mark. Select at random any inmate of a young offender institution, and you will almost certainly find a heart-breaking history of personal misery, professional neglect and lost opportunities.12

This makes for a powerful case for early intervention to prevent future offending (see Box 1.1).

Box 1.1: Young people in custody: a catalogue of misery

Government statistics13 show that if you randomly choose 100 young people aged 15–18 from youth custody, on average:

• 44 will have a history of local authority care;

• 75 will have lived with someone other than their own parents at some point in their lives and 45 will have lived in unsuitable accommodation in the 12 months before sentencing;

• 25 will have suffered violence at home;

• 55 will not have had access to full-time education prior to custody and 28 will have had no education at all prior to custody;

• 50 will have literacy and numeracy levels below that of an 11 year old and 25 below that of an average seven year old;

• 85 will show signs of personality disorder and 31 will have mental health needs, including depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress;

• 72 will have used cannabis ...