![]() Part 1

Part 1

Diagnosis: Understanding trends and challenges![]()

CHAPTER 2

Global trends and our urban future

Even if the Earth’s population stabilises toward the end of the century, as many demographers project, urbanisation will continue. The world is on the threshold of change as consequential as any in the history of civilisation

Harm de Blij, The Power of Place, 2009

Introduction

The world is becoming increasingly urbanised, and the future wellbeing of both humanity and the planet are inextricably linked with our success or otherwise in dealing intelligently with urban growth and change. In recent years, however, it is globalisation – and not urbanisation – that has become the buzzword in public policy debates.

There is now a massive literature on the impact of globalisation on the future of society. But what does the term mean? Hopkins (2002, 16) defines globalisation as ‘a process that transforms economic, political, social and cultural relationships across countries, regions and continents by spreading them more broadly, making them more intense and increasing their velocity’. Hutton and Giddens (2000, vii) adopt a similar perspective in their analysis of globalisation, and suggest that: ‘It is the interaction of extraordinary technological innovation combined with the world-wide reach driven by global capitalism that gives today’s change its particular complexion’ (2000, vii). Moynagh and Worsley (2008, 1) keep it nice and simple and define globalisation as: ‘… the world becoming more interdependent and integrated’. Underpinning all these definitions is the idea that global economic competition and international cultural exchange, coupled with the remarkable expansion of the Internet and modern communication technologies, are shrinking the planet.

This literature on globalisation is important and it deserves our attention. But our intoxication with all things global may have obscured the fact that another equally important process is also taking place – urbanisation. True, globalisation and urbanisation are inter-related processes, and some writers on globalisation have illuminated this interplay (Birch and Wachter 2011). But, in my view, urbanisation is a distinct process that deserves to be given much more attention. In this chapter I examine the astonishing movement of people to cities and sketch the contours of our global urban future. The urban areas of the world currently have a population of around 3.6 billion. By 2030 the United Nations (UN) expects this urban population to have grown by 1.4 billion. This change signals a spectacular increase in the number and size of cities – a shift that poses many challenges for civic leaders.

This chapter discusses this expansion of cities, considers where this urban growth is expected to take place, and examines the reasons why more and more people are moving to cities. Despite its importance the implications of urban migration for city governance have been sorely neglected. The chapter explores who the urban migrants are, and opens up a discussion of the challenges facing those concerned with the leadership and governance of increasingly multicultural cities.

The explosion of the urban population

The growth of cities is nothing new. But the rapid increase of the urban population in recent decades is unprecedented.1 While there is variation across the world, many cities are now growing at a formidable speed. A consequence is that more people now live in urban areas than ever before. More than that, ever since 2007, the urban population has outnumbered the rural. There is no doubt that, taking a global perspective, urban growth is set to continue, and that the urban population of the world will continue to climb at a startling pace. This urban expansion represents an extraordinary shift in the geo-politics of the planet that, even now, is not well understood.

First, let’s consider the basic figures on population growth. Demographers and geographers argue about the details of this remarkable spatial transformation and there are, in fact, significant definitional challenges. For example, there are notable differences of view regarding how big a settlement has to be before it can be described as an ‘urban’ area.2 The UN website does, however, provide us with good data on global urbanisation, and I use this source in the discussion that follows:

Between 2011 and 2050, the world population is expected to increase by 2.3 billion, passing from 7.0 billion to 9.3 billion. At the same time, the population living in urban areas is projected to gain 2.6 billion, passing from 3.6 billion in 2011 to 6.2 billion in 2050. (UN-DESA 2012, 1)

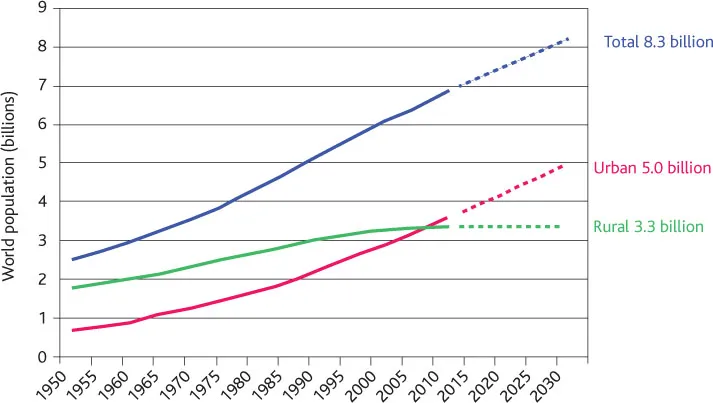

If we turn our attention to the relatively near future – the period between now and 2030 – the world population is set to rise from just over 7.0 billion in 2011 to around 8.3 billion in 2030 – see Figure 2.1. By then in the region of 5 billion people (or around 60 per cent of the world’s population) will live in urban areas. This is a staggering increase in the world urban population in a comparatively short time span. Consider this. The population of Greater London is around eight million. This means that an urban expansion of 1.4 billion (from 3.6 to 5.0) is equivalent to adding over 175 cities the size of London to the global urban landscape in less than twenty years. Except, as we shall see, they won’t look that much like London. In marked contrast to spiralling urban growth, the world rural population is projected, as shown in Figure 2.1, to level out and, indeed, to start decreasing in the period from around 2020.

From the point of view of public policy it is important to record that this rapid expansion of cities is mainly happening in areas that have not been dominant in past patterns of urbanisation. Rates of urbanisation vary dramatically between the more and less developed countries. Indeed, in some parts of the world it can be claimed that cities, or at least the central areas of some conurbations, are shrinking. UN demographers are clear that the vast bulk of the projected world population growth will be in the less developed regions of the world (UN-DESA 2012). As Mike Davis points out in Planet of Slums, most of the new urban residents are not going to be dwelling in elegant cities made of glass and steel:

Instead of cities of light soaring toward heaven, much of the twenty-first century urban world squats in squalor, surrounded by pollution, excrement, and decay. (Davis 2006, 19)

Robert Neuwirth, in Shadow Cities, estimates that there are about a billion squatters in the world today, and that this number is expected to double by 2030 (Neuwirth 2005, 9).

Birch and Wachter (2011) have assembled a useful collection of papers providing an overview of the various dimensions of global urbanisation, covering population trends, spatial planning, urban governance, finance and other aspects. They point out, politely of course, that the rise of urban populations, with their associated development issues, ‘calls into question the tendency of many social scientists to measure and analyse national-level data and to ignore spatial variations’ (Birch and Wachter 2011, 4). They are right, of course. In Chapter 1 I explained how ‘seeing like a state’ distorts understanding and holds back fruitful analysis, and I also suggested that ‘seeing like a city’ has advantages.

The Stiglitz Commission, set up by President Sarkozy of France, examined global statistical measurements, and concluded that many global metrics – measures like GDP and GDP-per-capita, inflation, and unemployment – are flawed, and made suggestions for improvements (Stiglitz et al 2009). The report makes many helpful suggestions on how to measure prosperity, but even this well respected commission left out ‘level of urbanisation’. This is to ignore a critical dimension of societal change. Birch and Wachter lodge this criticism but, in more hopeful vein, they also suggest that world leaders do, at least, now have an increasing capacity to add an urban lens to their assessments. There is evidence that major international organisations – like the United Nations and the World Bank – are redirecting their efforts to take account of urbanisation.3 And the international organisations representing cities are becoming increasingly effective in pointing to the importance of the ‘urban dimension’ in international public policy.4

Unpacking the dimensions of urban growth

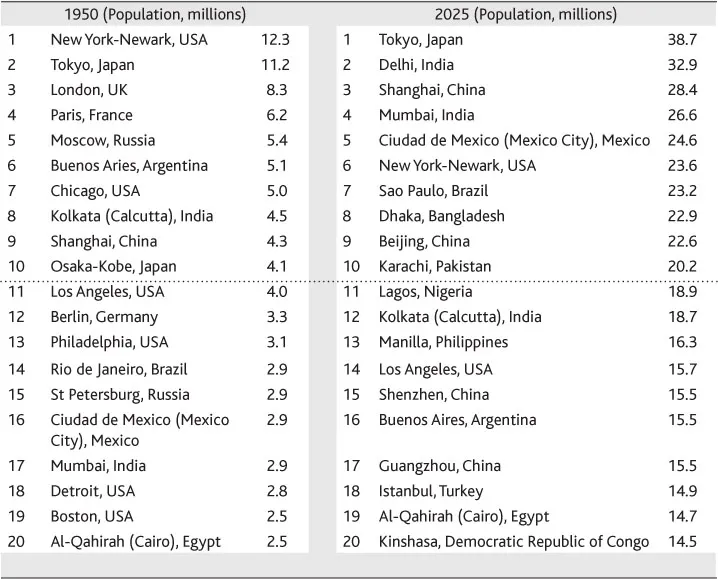

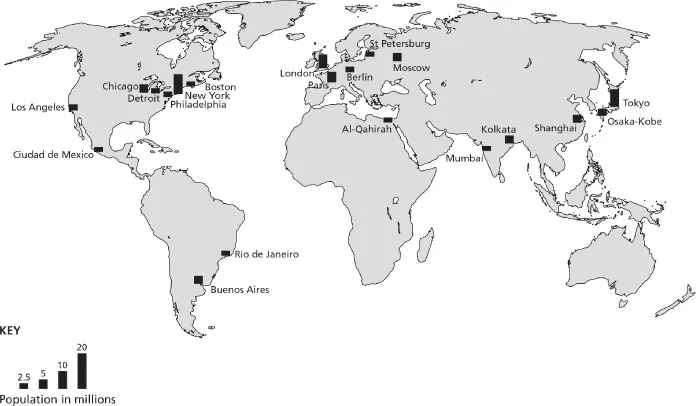

As explained in Chapter 1 place matters a great deal; moreover places are very different. It follows that we must guard against generalising too freely about ‘global urbanisation’. However, accepting this caveat, we can identify a number of striking features about international urban trends. The first point to highlight is that urban areas are growing at a faster pace than ever before. This is because, as shown by Figure 2.1, the total world population is rising steeply and because the urban share of the world population is also increasing. Second, today’s cities are bigger than ever before. For example, in 1950 the world had two megacities, cities with a population of over ten million – New York and Tokyo. Now it has over twenty. Third, the distribution of the urban population is shifting dramatically. The bulk of urban growth is now taking place in the developing world. I offer a table and a couple of world maps to illustrate aspects of these dynamics.

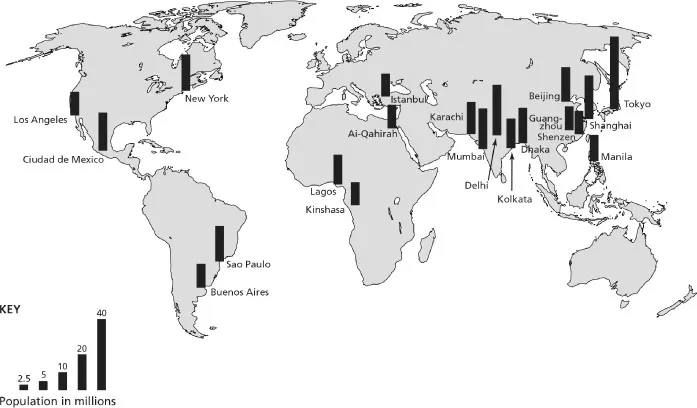

Table 2.1 lists the twenty largest cities in the world in 1950 and 2025. Figures 2.2 and 2.3 show where these cities are located, and the graphics on the maps give a visual indication of the size of these really big cities. New York City was the largest city in the world in 1950 with a population of 12.3 million, and five other US cities are also listed in the 1950 ‘top twenty’ (Chicago, Los Angeles, Philadelphia, Detroit and Boston). In 1950 Europe had three cities listed (London, Paris, Berlin) and Russia two (Moscow and St Petersburg) – see Figure 2.2. Spring forward to 2025 and, while the US still has two cities listed (New York and Los Angeles), Europe and Russia do not even feature. As Table 2.1 shows almost all of the ‘top twenty’ megacities in 2025 are in developing countries.

Figure 2.3 fills out the picture and reveals the spectacular growth of megacities in China, India and neighbouring countries, as well as the emergence of megacities in Africa (Lagos, Al-Qahirah and Kinshasa) and Latin America (Ciudad de Mexico, Sao Paulo, Buenos Aires). The map shows not just that the big cities of the future are mainly in different places than in the past, but that these megacities are set to be truly enormous. These cities have populations that are far bigger than many countries. Indeed, the top ten megacities – those with populations over 20 million in 2025 – will each have a population that exceeds the current total population of whole groups of countries. For example, the combined population of Denmark, Finland, New Zealand and Norway is, at present, less than 20 million. The UN estimates that the number of megacities in the world is expected to grow from 23 in 2011 to 37 in 2025.

It is, perhaps, not surprising that the megacities tend to attract the headlines and the television documentaries – the world has not seen such massive urban agglomerations before. However, it is a prevailing myth that the megacities contain, or will contain, a large proportion of the world urban population – the reverse is the case. The UN provides data relating to cities in five population bands: less than 500,000 (minor cities); 500,000 to 1 million (small cities); 1 to 5 million (medium-sized cities); 5 to 10 million (large cities); and 10 million or more (megacities).5 Several striking points emerge. First, taking the distribution of the urban population in 2011 – the 3.6 billion mentioned earlier – we can note:

- most of the world’s urban population – slightly more than 1.8 billion (51%) – lived in minor cities (under 500,000);

- around 1.4 billion (39%) lived in small to large cities (500,000 to 10 million);

- around 360 million (10%) of the world’s urban population lived in megacities (10 million or more).

Second, the UN predicts that the world urban population will increase by around 1 billion (from 3.6 to 4.6 billion) in the 2011–2025 period. Note that:

- most of this urban expansion – around 620 million (62%) – is expected to take place in cities with a population of less than 5 million;

- the number of megacities is expected to grow significantly (from 23 megacities to 37) and these cities are expected to account for 13.6% of the world urban population in 2025.

This discussion highlights the remarkable variation in the scale of the challenges facing city leaders in different localities. At one extreme we can see that developing effective place-based leadership and governance f...