![]()

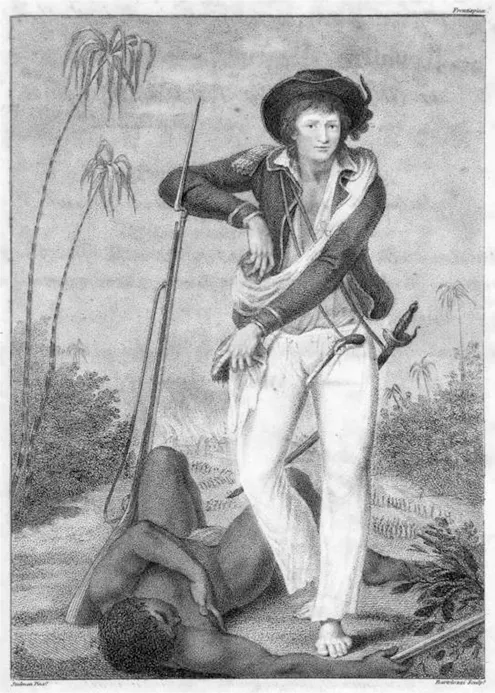

In this image (Figure 1.1), a white clothed soldier stands above the bleeding body of a Black Maroon. The image refers to a story circulated in a colonial travel narrative written by John Gabriel Stedman, printed in London in 1790 (Narrative). The allusion is to Stedman’s experience on an international military campaign designed to subdue a very powerful and successful Maroon revolt in Suriname between 1772 and 1779. The visual rhetoric revolves around a number of contrasts: clothed/naked, standing/lying, living/dead, white/black. The inscription tells of a physical blow felt by the Black warrior and of the wound suffered by the unwilling white executioner. The body of the black man is sublimated into the wound felt by the white European man who defends his privilege. The material exercise of colonial domination is translated into the colonist’s moral sentiment. The physical pain and injustice suffered by enslaved Blacks represented by this single Maroon figure become occluded by the noble abolitionist sentiments of a soldier who represents white Europeans and fellow colonists. A familiar story is thereby told – a story in which European subjectivity is structured according to the internalization, sublimation, and, ultimately, the denial of the suffering of the victim.

But let us read it again. There are two elements that disturb this familiar narrative and open possibilities for further analysis. First, there is a residue of corporeality, of spectacularity, that remains on the scene (the Black Maroon on the ground, codpiece over his genitalia; the white soldier pointing, demonstrating something that eludes the reader/viewer). The presence of this undisciplined body requires us to read, think, and look again through another signifying grammar that might yield another story, one no more certain and yet nonetheless crucial: a story of Black resistance. Second, what is the dominant subtext of this plate? Is it Hegel’s master–slave dialectic? If it is, then which of the figures dominates? Which one feels the wound? Which one inflicts it? The “I” who claims to feel the wound does not fully contain it and the answers float dangerously between the two.

This floating signifies the symptomatic undecidability of the grammar of the colonial archive. While violently trying to consolidate its hegemonic identity, Europe flounders, a crack appears in its discourse. This grammar consistently fails to ensure that the image will tell the story of European domination without also telling that of its violent intimacy with the oppressed. The most fundamental lexical unit of The Colonial Art of Demonizing Others is the figure of the dehumanized, demonstrated (as in de-monstrated: un-shown) and monstrified human being. In the decades leading up to and following the Haitian Revolution through the period of European Abolitionism, abject figures of enslaved and colonial peoples crowded the archives, and permeated the literature and visual culture of the colonial powers.

Figure 1.1 William Blake. From Different Parents, Different Climes We Came (Frontispiece, Plate 1). Narrative. John Gabriel Stedman.

Such figures constitute fascinating instances of counter-esthetics in counterpoint to dominant esthetic modes. But we can also read them as symptoms of the European archive’s disavowed but intimate, even mimetic, relation to the Others it cannot help representing. In particular, it is the colonial subject’s political and ethical claims upon the emerging body of the European imaginary that are both represented and distorted. Inasmuch as these claims must fall under the incipient universalism articulated by the doctrines of the Enlightened metropolis, they fall outside of the regime of universals that Europe was marshaling. When, from the city of London at the end of the eighteenth century, Blake (America) re-imagined the American struggle of independence after the Haitian uprisings, he had been working closely with Stedman’s colonial account of a military suppression of a revolutionary Maroon community in Suriname a few decades before. The images Blake uses derive directly from the images of crucified and tortured Black bodies – the “transfigures” – that appear in Stedman’s journal. But, as I read Blake’s renditions, I hear a different story. As it moves from Stedman’s journal into Blake’s artwork, from Suriname to London, this transfigure (and its translations in subsequent media forms) suggests that Stedman’s representation of Black abjectness unwittingly encodes Black agency and colonial self-horror at the monstrosity of colonial violence. My reading of the transfigure will demonstrate that even the most dehumanizing representations of Black people in the colonial archive can be read as evidence of radical Black agency in the Caribbean and, paradoxically, as evidence of Europe’s horror at itself.

Beyond the organizing lexical figure of the monstrous, de-monstrated colonial body, disparate colonial documents, visual images, objects of expressive culture, and literary narratives work as grammatical units in covert narratives that are only partially legible through a poetics of withholding. These objects of study coalesce across national, linguistic, and epistemological boundaries into a broad social text where shared social narratives do not just exist side by side, but are interlocking nodes in a transnational, multilingual, multilocational, and mobile network of meaning, documentation, self-activity and knowledge. Agents, witnesses, interpreters, and participants in these networks produce and translate symbols of self-activity across space, language, and nation.

I use the word “translation” to describe the processes through which these lexical units and grammatical nodes carry over from one specif c, national-linguistic archive to another. Such processes uncover symptomatic nodes in a still relatively unexamined register. The latter are not, as a comparatist approach might prefer it, distinct symbols or representations that arise through discrete histories and national boundaries. Rather, they present conflicting and complex versions of each other, emerging unevenly in many languages, through diverse forms of cultural expression and in disparate geographic locations. Part of a necessarily discontinuous network, these nodes are necessarily imprecise translations of each other. Legibility as translation occurs only in a conflicting, complex, multilingual, multilocational, and multivocal reading. When read together, the story told unravels the symbiotic relationship between Europe and enslaved peoples.

These nodes tell a multivocal story of Europe’s sustained dehumanization of Black people, of Black people’s consistent self-assertion, resistance, hope, and rage; of Black people’s unfailing self-activity; of European and colonial societies’ frenzied disavowal of the beastliness of Europe’s systematic oppression of Black people. The figure of Solitude, a Guadeloupian Maroon who fought alongside Louis Delgrès and Joseph Ignace against the French in 1802, was almost entirely lost to the colonial archive. Yet she was remembered in the collective archive of Guadeloupian oral history. About fifty years after the re-enslavement of the people of Guadeloupe, colonial historian Auguste Lacour dedicated a few lines to Solitude’s arrest and defeat, a seemingly small but necessary detail in his history of the colony. Here, as in the case of the fig-ure of “Neptune” (see Chapter 2), we have what appears to be a narrative of European colonial success: the Maroon warrior called Solitude is dead. But when André Schwarz-Bart picks up the figure of the same woman and re-tells her story in 1972 according to Guadeloupian oral tradition (La Mulâtresse Solitude), readers find something different: at the core of the colonial cruelty that Solitude and thousands of other people endured during the time of the revolutionary period is a supplement to the story of the victorious master, a solid narrative of European success and superiority. It is not simply the story of the endurance and fortitude of revolutionary Black woman that the colonial archive wants to erase. In addition, a garbled story comes through the figure of Solitude – a story about the inextricability of Black Guadeloupians and their freedom struggle from the French revolutionary imaginary.

As is appropriate to the objects it analyzes, the theoretical framework of this book is multilingual and multilocational. My approach grows out of two major contrapuntal thinkers of the counter-colonial tradition – C.L.R. James and Fernando Ortiz. The latter’s Contrapunteo Cubano appeared in 1940, just two years after James’s Black Jacobins. Translated into English in 1995, Ortiz’s book provides an account of the social history of sugar and tobacco. Both James’ narrative of the Haitian and French Revolutions and Ortiz’s study of the Cuban sugar and tobacco trade were singularly important works from a methodological standpoint: rather than telling the story of colonialism and resistance to it through a single nation or unified geographic area, James and Ortiz suggested that the history of the colonial Caribbean must be approached through what we might, through Frederic Jameson, refer to as new ideologemes, new grammatical or symbolic nodes in a new historio-graphical lexicon – Jacobins in the case of James, tobacco and sugar in the case of Ortiz. Furthermore, both Black Jacobins and Contrapunteo Cubano employed a “contrapuntal” approach. Both works are dedicated to recovering and presenting, as if in back-steps or hidden musical beats, events and figures that have been, like the Maroon on Stedman’s Frontispiece, systematically obscured or neglected. The Colonial Art of Demonizing Others departs from the contrapuntal grammars of James and Ortiz. It is not a matter of saying that the Euro-Caribbean archive is contrapuntal – a matter of parsing out a dominant and an obscured voice, a point shadowed by counterpoint, a hegemonic historiography by a history of the oppressed. Instead, this archive is composed of a lexicon of contrasting narrative tongues, registers, cultural locations, and sometimes contradictory figures and incompatible grammars. My book multiplies the contrapuntal approach to read in three figures (“Neptune,” Jean François, Solitude) an interdependent set of nodes within the dominant archive.

George Rawick writes:

it is not enough to assert that the history of black people has never been made integral to the history of the American people, or that the voices of the slaves have rarely been heard. There must be sources that demonstrate that white society cannot be understood without seeing its symbiotic relationship to black society.

(From Sundown to Sunup: 14)

The Colonial Art of Demonizing Others multiplies Rawick’s call to scholars of American culture and history. The need to find and develop sources that will form the basis for a counter-history of domination and cruelty into a multilingual and multilocational study of a series of symbolic nodes of the colonial archive is urgent. My study demonstrates that white societies of Europe and the colonial world cannot be understood without seeing their symbiotic relationship to the Black people, and that European colonial subjectivity was deeply intertwined with Black colonized peoples.

Eugene Genovese’s insight that “ideological conditioning” laid the basis for a race-based slavery whose growth “transformed the [ideological] conditioning from a loose body of prejudices and superstitions into a virulent moral disorder” is also useful to understanding how The Colonial Art of Demonizing Others develops a symptomatic reading of colonial state discourse as illustrative of the “virulent moral disorder” of Europe (Genovese, The World the Slaveholders Made: 105).1 Every dehumanizing representation of Black people, every document of successful colonial violence against Black freedom fighters revealed this “virulent moral disorder” and withheld any and all depictions of Black people’s expression of their humanity. Every transfigure, then, contains a self-loathing indictment of the beastliness of the repressive and violent practices of colonization and enslavement that sustained Europe and colonial societies in the Americas.

A.J. Greimas’s proposal of the primacy of narrativity as an object of study in itself is useful to understand my method. In his grammar, narrative is a mode of thinking – it is a continuous process of narration, negotiation, and production of meaning based in continuous mistranslations.2 These mistranslations serve dominant narratives and ideological frameworks. They misunderstand and cause violence to the subject/object being represented. The Colonial Art of Demonizing Others re-translates the rhetorical violence of the dehumanizing images of the colonial archive into stories of pride, hope, hurt, and acute humanity. Representational violence (which Donald Pease, in The New American Exceptionalism, tells us lays the groundwork for material violence) opens up the possibility of seeing other languages, other grammars that enable re-translations of the sustained narrative of dehumanization of the archival record.3 But, as Jameson warns us in his introduction to Greimas’s On Meaning, these re-translations are never totalizing. They are always necessarily incomplete, opening onto more translations. Every translation invites another translation. These stories are told in a language and grammar that is both contained in and disruptive of the language of colonial domination and dehumanization. My book re-translates images and narratives that made possible and even desirable the processes and effects of dehumanization. Narratives of colonial domination written by colonial administrative documents infused with imperializing ideologies become complex narratives of struggle and resistance to colonial and racial domination.

The Colonial Art of Demonizing Others responds to Jameson’s injunction to create – in a process of what he terms grammatical bricolage – new units of language capable of telling new stories. Greimas’s semiotic reduction (whereby a text is reduced, or re-written, into more fundamental mechanisms of meaning) is useful to further understand how this book makes use of the trans-figure. Bending Greimas’s notion of semiotic reduction to my purposes, the image of the abject human being can be understood as the most reduced, and therefore the most productive signifier of the stories of struggle and freedom that speak through these images. In a grammar of the symptom, a grammar that reads in tongues – at multiple registers, disparate geographic locations and multiple nation-based lexicons – the transfigures are fundamental to the re-writing of the colonial archive.

Transfiguration, translation, and the monstrous (trans) figure are the pivotal strategies of The Colonial Art of Demonizing Others. Why the monstrous figure? The monstrous-transfigure is the point of suture between the colonizer and the colonized, retaining the psychic effects of colonial violence on both. Why transfiguration? As an analytical tool, transfiguration serves as a capacious rubric. It encompasses multiple strategies necessary to comprehend the transfigure, the figure represented as monstrous. It tracks the changing representations of the monstrous figure as it moves across linguistic and cultural terrains. As a theoretical horizon, transfiguration makes sense of the multiple referents of the transfigure: Black agency and European fear of it; the inherent justice and inalienable humanity of Black radical activity; and European horror at its own monstrosity. The complexity of the monstrous/transfigure has to do with the intimate relation of this figure to colonial acknowledgment of its own monstrosity. Colonial discourse initially produces the monstrous figure as a psychic weapon against Black radicalism. Yet, the materiality of the figure retains the traces of agency that the European imaginary attempts to contain, and brings news of something else: it tells of the inalienable agency, humanity, and the undeniable logic of Black radicalism and the people that pursued it.

Translation, according to Tejaswini Niranjana (Siting Translation), is a strategy of containment that serves to bind the colonized into the status of what Edward Said termed “objects without history” (Said and Donato, “An Exchange,” cited in Siting Translation: 3). Niranjana reminds us that the site of translation illuminates conflicting stories that attempt to account for inequalities of relations between peoples, races and languages. We learn from her that the practices of subjectification a...