![]()

1

‘Dead Man’s Penny’: a biography of the First World War bronze memorial plaque

Julie Dunne

Over the last two decades, there have been fundamental changes in the way that material culture has been studied, with a general acknowledgement now that objects or ‘things’ can be transformed by their relationships with people, and vice versa (Miller 1994; 2005; Pels 1998). In this new interdisciplinary interpretative analysis of material culture, we recognise that, as Kopytoff (1986) proposed, artefacts can carry lengthy biographies encapsulating various meanings that have accumulated through their production, use and deposition.

However, Kopytoff (1986) focused more on how the economic or exchange value of objects shifts as a culture changes. It was Gosden and Marshall (1999) who suggested that, through social and cultural processes, objects gather multiplicities of meanings, which may change in significance through time, place, and ownership, and that of course, the transformations of objects and people are inextricably entwined (ibid.: 169).

Illustrating this liberating but complex realisation was Strathern’s (1988) observation that in Melanesian culture a person is ultimately composed of all the objects they have made and transacted, and that these objects represent the sum total of their agency. Gell (1998), similarly, recognised that objects can have agency and can be construed as ‘social actors’. It has been argued that material culture has the potential to shape our experiences of the world, not just in terms of physicality or ‘being’ – the moving through and negotiating with material forms in everyday life – but also, symbolically, as metaphor (Cochran and Beaudry 2006: 196). The application of these anthropological ideas to modern conflict archaeology is in its infancy, yet the significant potential of such an approach is revealed in one small kind of object explored here.

* * * * *

During the Great War of 1914–1918, the British government recognised the need to both honour the fallen and show some form of official individual (rather than collective) gratitude to the deceased’s next of kin. This personalised commemoration of the dead took the form of a Bronze Memorial Plaque that became known, variously, as the ‘Dead Man’s Penny’, the ‘Next-of-Kin Plaque’, or the ‘Death Plaque’ (Dutton 1996: 63).

For the bereaved, these plaques, sometimes displayed in domestic shrines, would have been anchoring points for emotion, memory, and meaning, and may have come to render ‘present’ those who were so painfully absent. This entanglement and association with the deceased acted to sustain their social presence but also accumulated layers of meaning which, as Joy (2002: 132–133) suggests, can have greater strength and significance where they relate directly to warfare. For me, the Dead Man’s Penny also has a strong resonance as what Sherry Turkle (2007) calls an ‘evocative object’, something which, as an ‘emotional and intellectual companion’, can fix memory. Indeed, Turkle argues that thought and feelings are inseparable, and that ‘we think with the objects we love, we love the objects we think with’ (ibid.).

However, with the passage of time, these artefacts, like many small-scale war memorials, passed out of memory and became largely forgotten and unnoticed. Today, the Death Plaque is part of the material culture that has come to symbolise the enormous trauma, destruction, and loss which marked the devastating experience of the world’s first global industrialised war. These objects are now accumulating further multifaceted layers of meaning as they are collected, researched, traded, and displayed in public and private collections. In this biography of the Dead Man’s Penny, the complex process of transformation and entanglement between people and objects which sees meaning given to inanimate things is revealed as the same process by which meaning is given to human lives.

‘Memento of the Fallen: State Gift for Relatives’

The start of the Great War was marked by a mood of great optimism, and a surge in patriotism, which saw queues of volunteers at military depots eager to join the ‘just and noble cause’ of making the world safe for democracy. By 1916, however, people at home in Britain were becoming aware that a new kind of industrialised warfare had arrived. The first mass global war of the industrial age saw both sides inhabiting endless miles of warren-like trenches, and fighting a war of stasis and attrition; images of the Western Front portrayed uncanny and desolate landscapes, thick mud, endless craters, blasted trees and barbed wire (Saunders 2001: 37–39).

When the Battle of the Somme began, on 1 July 1916, the lifeblood of young British men began pouring onto the landscape of the Western Front (Dutton 1996: 62). Soon, telegrams began arriving from the British War Office in London, and across Britain, and whole streets and entire towns suddenly found that they had lost great numbers of young men.

These telegrams, and the depressing daily casualty lists, came to represent the wastefulness and futility of the war to many British soldiers and civilians. By the end of 1916, as the Somme Offensive was coming to an end, David Lloyd George, the Secretary of State for War, recognised the need to show some form of official gratitude to the next of kin of the soldiers and sailors who had died on active service, and set up a committee to decide what form the memorial should take.

The decision was announced in The Times on 7 November 1916, under the headline ‘Memento of the Fallen: State Gift for Relatives’. The newspaper article stated that the precise form of memorial was under consideration, but that it had been initially accepted that it should be a small metal plate recording each man’s name and services, and paid for by the state. Bearing in mind that the war was not going well for the Allies at this time, the decision manifests a spirit of grim optimism (despite its tragic overtones), and also implied an intractable faith in ultimate victory (Dutton 1996: 63).

Included on the committee were two peers, six members of parliament (two of whom held military rank), and representatives from the Dominions, the India Office, the Colonial Office, and the Admiralty. Sir Reginald Brade, Secretary of the War Office and Army Council, was appointed Chairman, and Mr W. Hutchinson, also of the War Office, was made Secretary. A specialist sub-committee was set up to deal with technical and artistic detail. This was composed of Sir Charles Holmes, Director of the National Gallery, and Sir Cecil Harcourt-Smith, Director of the Victoria and Albert Museum, along with George Frances Hill, Keeper of the Department of Coins and Medals (and later to become Director) at the British Museum. It was Hill, a renowned expert in the cast metal works of the Italian Renaissance, who took overall responsibility for managing the design and production of the plaque (Dutton 1996: 63).

The official instructions regulating the Competition for Designs for a memorial plaque to be presented to the next-of-kin of members of His Majesty’s Naval and Military Forces who have fallen in the war were published in The Times of 13 August 1917, some nine months later. The committee announced that the form of the memento would be decided upon as a result of a public competition, with prizes for the best designs totalling £500 (in proportions to be subsequently decided) (Anon. n.d.a).

The committee decided that the commemoration plaque, which would be cast from bronze and must be ‘finished with precision’, should cover an area as near as possible 18 square inches (c. 45.7 cm2), which could be either a circle of 4¾ inches (11.4 cm) in diameter, a square of 4¼ inches (39.8 cm), or a rectangle of 5 inches by 53/5 inches (12.7 × 14.2 cm). The design should be simple and easily understood, and include a subject, preferably some symbolic figure, and incorporate the inscription HE DIED FOR FREEDOM AND HONOUR. Space must be left for the deceased’s name either in a circular design (around, or partially around the margin), or a square or rectangular form at the base (Anon. n.d.a).

Further instructions stated that all competitors ‘must be British born subjects’ and that the models, which should be made of wax or plaster, should be packed in a small box and delivered to the National Gallery in London no later than 1 November 1917. Works were not to be signed but marked on the back with a pseudonym, and accompanied by a sealed envelope bearing the same on the cover, and containing the competitor’s name and address. Finally, it was stated that the artist’s signature or initials would appear on the finished plaque (Anon. n.d.a).

Interest in the competition, particularly from overseas entrants, was considerable, as just four weeks later, on 10 September; it was announced in The Times that the closing date for submissions had been extended to 31 December 1917. Details of this extension were repeated in the paper the following month, together with a report of the scheme’s good progress. The article also stated that:

In addition to the plaque, a scroll with a suitable inscription will be given. This is being designed at the present moment and it is hoped that it will be possible to put printing in hand in less than a fortnight. (Dutton 1996: 64)

Unfortunately, this proved to be hopelessly optimistic, as manufacture of the scrolls did not begin until January 1919, having been beset both by technical problems and also shortages of paper and ink (ibid.).

The competition was popular, with over 800 designs being received from all over the Empire, the old Western Front, the Balkans, and the Middle Eastern theatres of war, as well as from many artists based at home in Britain (ibid.). Sadly, it seems likely that some of the competitors may themselves have ‘passed out of the sight of men’ and had their own names recorded on the memorial plaque.

On 24 January 1918, the committee, and its specialist ‘artistic’ sub-committee, met to judge the entries, although the results of the competition were not announced until 20 March 1918. The day after this, the Germans launched the Spring Offensive or Kaiserschlacht (Kaiser’s Battle) on the Western Front, in a last attempt to defeat the Allies before the United States’ forces were deployed against them (Dutton 1996: 65). However, the early dramatic German successes might have led many to feel that issuing a memorial plaque showing the British lion defeating the German eagle was hubristic at best.

The winning entry, Pyramus, was submitted by sculptor, painter, and medallist Edward Carter Preston of the Sandon Studios Society, Liverpool, who received a prize of £250. The second prize of £100 was awarded to Moolie – produced by the sculptor and medallist Charles Wheeler. Third prizes of £50 each were issued to Zero by Miss A.F. Whiteside, Weary by Sapper G.D. MacDougald, and Sculpengro by William McMillan (who later designed the Allied Victory medal). Nineteen other competitors were deemed ‘worthy of honourable mention’. The King approved the design as did the Admiralty and the War Office (Dutton 1996: 64–65), although clearly G.F. Hill was not overly impressed, as he remarked in his (unpublished) autobiography ‘no-one of which (design) could be regarded as of outstanding merit’ (Anon. 1986: 25). The prize-winning designs were exhibited at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London during the spring and early summer of 1918 (Dutton 1996: 69).

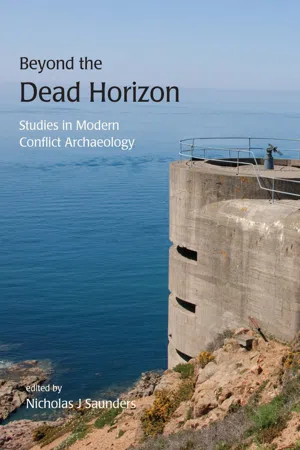

The winning design depicts Britannia, classically robed and helmeted, and supporting a trident, respectfully bowing her head whilst granting a crown of laurel leaves, symbolic of triumph, onto a rectangular tablet bearing the full name of the dead soldier (Figure 1.1). No rank is shown, as it was intended that no distinction would be made between the sacrifice made by officers and other ranks.

Figure 1.1: First World War Bronze Memorial Plaque commemorating the author’s great-grandfather, William James Collins. (© author)

The stylised oak leaves are symbolic of the distinction of the fallen individual. The dolphins represent Britain’s naval power, and the lion, originally described as ‘striding forward in a menacing attitude’, represents Britain’s strength. Interestingly, the proportions and unusually low profile of the male lion were queried by Sir Frederick Ponsonby on behalf of King George V, and also caused some controversy among the public, in particular, deeply upsetting the officials at Bristol’s Clifton Zoo.

In a letter to The Times on 23 March 1918, the zoo’s Honourable Chairman, Mr Alfred. J. Harrison, and the Head Keeper, Mr J.F. Morgan, forcefully attacked the lion as ‘a meagre big dog size presentation’, and as ‘a lion which almost a hare might insult’. They argued that Carter Preston’s lion could not have been modelled from real life, and certainly not from the ‘fine male specimen in Clifton Zoo!’ Within the exergue, in symbolic confrontation, another lion, a symbol of British power, is shown defeating the German eagle. The committee had some concerns over this as it was felt that the eagle should not be shown to be too hopelessly hu...