![]()

1

Defining Curriculum: Towards a Conception of Curriculum as Educational Praxis

One of the first problems that confronts students of curriculum when they embark on a course of study is what the term "curriculum" itself means. Probably the most widely held view is the rather unproblematic assumption that curriculum is simply the content or knowledge conveyed by particular school subjects. For some, this idea may be confirmed by the widespread use of curriculum guides, syllabuses, programmes and packages in schools that display as a prominent feature a body of knowledge that is to be taught to pupils. The study of curriculum, from this perspective, is the study of subject matter, and its creation, packaging, and implementation in schools.

There is a problem with this view, however, and it is that it gives us very little idea of how we might actually go about the task of studying the curriculum. How, in the first place, do we identify problems and issues, what these are, or even if they do in fact exist? What methods can be legitimately used to pursue these? And how will we know whether the solutions we derive are good ones?

In attempting to answer these questions, we can adopt one of two broad approaches. We can, on the one hand, accept the unproblematic equation of curriculum with content and borrow a theoretical framework from one of the already established disciplines in educational studies like philosophy or psychology or sociology, and use these frameworks to structure our studies. This approach is in fact fairly common in tertiary institutions, especially in universities, and it derives from a particular view of educational theory that I will discuss in more detail in the next chapter. At this point, it might be appropriate to sketch three general difficulties with this discipline-based view as a way of leading into our second option. First, there is a range of disciplinary frameworks to choose from, and our problem is deciding which one. One response to this issue might be that we adopt the most relevant perspective for our particular purposes in a given situation. This answer is fine as far as it goes, but it does presuppose that we already know or at least have some idea of what the problems are and what might count as good solutions before we even begin to study the curriculum. There is also the danger that by taking only one disciplinary perspective, focusing say on conceptual issues (philosophy), the individual pupil (psychology), or society (sociology), we risk touching in only a superficial way, or even missing entirely, a range of issues that may be of pressing relevance to educators in specific circumstances. We could, of course, choose to study the curriculum from a range of discipline-bases, and this indeed is what often happens in teacher education courses. The problem this creates, though, is that by using issues and concepts from a particular framework as lenses through which to focus our studies, the actual educational issues in which we are primarily interested become abstracted from the context in which they occur and are thus open to misunderstanding and distortion. There is also the further problem that disciplinary frameworks often offer contradictory explanations for occurrences in education, a situation that can only lead to confusion rather than enlightenment. I return to a discussion of these problems in Chapter 2. In the meantime, I want to argue that a disciplinary approach to curriculum studies falls short of providing the best means of studying the curriculum, particularly in teacher education courses.

In our second option, on the other hand, we may choose to view the "curriculum equals content" equation as problematic, and look to a more thorough understanding of the notion of curriculum itself for ways in which to study it. This involves an investigation of the ways in which the term "curriculum" is used, both in everyday talk about teaching and learning, and in its more rarefied employment in the research literature, with the aim of developing a more complete understanding of the meanings the word can be legitimately employed to convey. Significantly, we would also want to be able to discern the broad logical features of the term as it is used, with a view to developing from these features clues to how we can most appropriately study curriculum.

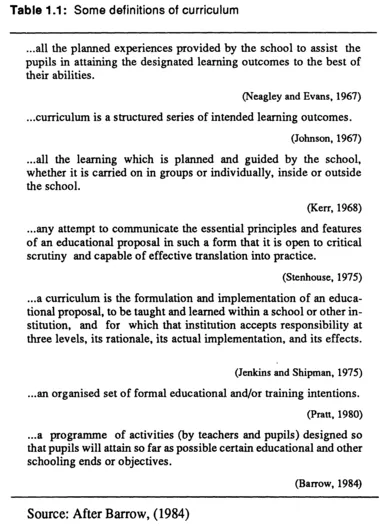

One way some curricularists have approached this task is simply to offer a definition of curriculum. By defining what they take the term to mean, they allow their readers to evaluate usefully their subsequent analyses for their logical consistency with the definition. But by doing this they are really only begging the question — what do we mean by curriculum? — rather than supplying a resolution. I will not be concerned to contest particular definitions here, but rather to synthesise its broad characteristics from the many ways in which curriculum has been defined.

The purpose of this chapter is to undertake such an analysis of the meaning of the term curriculum, and to provide a basis for the elaboration of a conceptual framework, in Chapter 2, that will outline the major ideas that underwrite the approach I have taken to curriculum study in this book. I begin by developing my comments on the problem of attempting to define curriculum, and then use this as a way of moving beyond definition to provide a more adequate conception. Through this chapter, I plan to show that the notion of curriculum, properly conceived, embodies the broad characteristics of subject matter, the pedagogic interactions of teachers and learners, and the sociocultural milieu in which these interactions take place. Curriculum study, I will argue, allows us to focus on educational praxis or the coming together of a number of elements that are commonly conceived as oppositional, such as theory and practice, individual and society, and intention and outcome. In this view, curriculum study is the study of these elements where they come together as educational action in schools. Our first task to be pursued in the next section is to work through the problem of definition.

The Problem of Definition

Some writers like Kelly (1982) have argued that a definition can only be at best arbitrary and so it is prudent not to attempt to tie down the meaning of the word too tightly. Kelly's suggestion, based on a recognition that the term is a complex and multidimensional one, is to allow curriculum to be understood within specific contexts for particular purposes. However, as Tripp (1984) has pointed out, this abdication of responsibility can lead to two problems — one, unless we define what we mean by the term curriculum, we are likely to be confused about what "curriculum study", "curriculum theory" and "curriculum research" refers to; second, by failing to define the term, there exists the danger of conveying the notion that the meaning of curriculum is, in fact, known to curriculum experts, and so is treated as unproblematic. Clearly, both points Tripp makes are valid, but his solution of simply stating his own,

apparently arbitrary, definition is more likely to confuse further than enlighten.

Barrow (1984), in making a number of similar points, lists eight definitions of curriculum by fairly prominent curriculum writers, and he shows that although some definitions share similar characteristics and concerns, few writers are able to agree on which features should be emphasised, or provide a consensus on the range of meanings the term "curriculum" may legitimately be used to convey.

He goes further to suggest that most definitions, as definitions, are poor in any case since they are often too broad and act as a "catch-all", and so are extremely difficult to put into operation. In this case, almost everything that happens in the school, from the transmission of formal school knowledge in classrooms, to standing in the lunch queue or smoking behind the gym block, can be part of the curriculum. In other words, the term becomes meaningless and so far from useful. The term "hidden curriculum" is sometimes used to distinguish between the formal learning teachers intend to take place, and the things pupils learn as unintended but unavoidable consequences of engaging in the formal curriculum. I will look more closely at the hidden curriculum in physical education in Chapter 7; at this point, it is important to reserve this term to acknowledge that pupils learn more than the content of courses that are planned and taught by teachers.

In contrast to this problem, definitions are sometimes too narrow and specific, and so cannot be used in a wider range of contexts. The danger in this second case is that much of value that perhaps deserves a place in the curriculum may be excluded. For instance, it may be that some people do not regard physical education as a proper subject (see Chapter 3) and so refuse to grant it a legitimate place in the school curriculum, preferring to treat it instead as a peripheral, fill-in activity. In this case, too narrow a definition may lead to important activities being omitted or dismissed as unimportant.

Although Barrow recognises that "meaning-in-use" of curriculum is now widely disparate from its dictionary definition, he suggests there may be something to be gained in understanding the etymological development of the word 1.

Egan (1978) provides one of the most detailed and insightful analyses of the etymology of curriculum. He shows that from its original use in Latin to refer to a "race" and "racecourse", it came in some contexts to refer to temporality, as in a career. Later, curriculum came also to refer to content, or "that which is contained" as well as, in the temporal sense, a container. A concern with suggestions of what schools should teach, and so with the notion of "curriculum-as-content" or subject matter has persisted to the present time, both in commonsense understanding of curriculum and in the work of some philosophers of education 2.

Egan argues, however, that the possibility of confining the meaning of curriculum to questions of content was undermined by the growth in interest and influence of educational psychologists, who began to investigate questions about individual learning differences, and by implication elevating to a level of some significance the issue of how the curriculum should be taught; he also attributes the child-centred movement with an important role in this process. Through these influences methodological issues, or how subject matter should be conveyed to pupils, have for some researchers become a dominant preoccupation in discussions of the curriculum. Egan goes on to argue (correctly, as I hope to show below), that any definition of the curriculum will include reference to questions of content and method; he concludes that this realisation opens the curriculum field up to the point where it becomes coextensive with educational research. In answer to his question "what is curriculum?" Egan replies "Curriculum is the study of any and all educational phenomena."

There are two problems with this answer, however. The first (following Barrow) is that the definition is too broad to be useful in an operational sense. If the term curriculum denotes all educational phenomena, then it has no power to allow us to discriminate between particular features and dimensions of the educational process. Under these circumstances, the term becomes redundant; it serves no purpose, because we already have terms which express the ideas we wish to convey. The second problem represents a more fundamental error because it is clear that Egan has shifted the focus of his discussions from "what is curriculum?" (that is, "what are the range of meanings the word can be used to convey?") to an answer formulated in terms of "what constitutes curriculum study?". This unannounced shift in focus is clearly neither helpful nor legitimate. This does not deny that what the term curriculum may refer to has profound implications for research, but it is important that we clarify the notion rather than, as Egan does, suggest that this is impossible and then confuse matters further by conflating "curriculum" with "curriculum research".

Beyond Definition

I would argue that although there are serious problems in attempting to offer a definition of curriculum, such as reifying the notion (Young, 1976), or treating it as unproblematic (Tripp, 1984), it is important that we are able to extrapolate some of the features of curriculum from "meaning-in-use" if we are to talk intelligibly about curriculum study and curriculum theory. In attempting to define curriculum for particular purposes, writers have often emphasised some specific features over others. As Young (1976) has argued, however, this partiality of view has lead to less adequate conceptualisations of curriculum. He suggests that two common misconceptions need to be overcome if a more holistic picture of curriculum is to be achieved. He refers to these misconceptions as "curriculum-as-fact" and "curriculum-as-practice". The former "presents education as a thing, hiding the social relations between beings who collectively produce it" (Young, 1976, p. 187). Young considers "curriculum-as-fact" which focuses exclusively on subject matter to be the dominant view currently, to the point where it is treated as "given", and people are unable to see the curriculum as an historically produced social reality which is underwritten by economic and political forces in society. When the curriculum becomes reified in this way, it works to prevent people from becoming "aware of ways of changing their world".

"Curriculum-as-practice, on the other hand, while it provides the valuable service of showing that curriculum is in reality created by people in interaction, and so is located in space and time, seems to overemphasise the autonomy of the actor. One consequence of this is that it quite inappropriately locates the classroom as the major site for social change through education. Young argues that the teacher is given the responsibility of bringing about change without an acknowledgement of the structures which constrain educational action. In other words, the view of "curriculum-as-practice" neglects to show how individuals' historically situated practices are structured. In summarising his position, Young argues for a "critical theory of curriculum" which moves beyond these two misconceptions of curriculum.

A theory that can provide for possibilities of change in education does not emerge either from the dominant view of "curriculum-as-fact", or from a critique as practice. The first, by starting from a view of knowledge abstracted from men in history and from the teachers and pupils to whom it is addressed, denies them possibilities except within its framework and definitions. The second, in its concern to recognise teachers and pupils as conscious agents of change, as theorists in their own right, and to emphasize the human possibilities in all situations has also become abstracted from the constraints of the teacher's lived experiences.

(Young, 1976, pp.189-190)

Young's critique suggests that a more adequate conceptualisation needs to move beyond definition towards identifying the broader features of curriculum. For instance, it is clear that people do more or less effectively use the term curriculum to communicate what they mean. For example, we speak of the "school curriculum", the "primary curriculum", and "physical education curriculum", each of which is manifestly different in form and content, but each also has recognisably similar features. In each case, the term conveys the sense of a body of knowledge, information, or content to be communicated; that this communication commonly takes place through the interactions of teachers and learners (although this is not to deny that materials, such as textbooks, computers, and so on may be used to aid communication); and this interaction is commonly located in a more or less institutionalised cultural and social context.

Towards a Dialectical Conception of Curriculum

The three broad characteristics of the word curriculum are, then, in abbreviated form: knowledge, interaction and context. There are two important points we have to note about this view of curriculum. The first is that each characteristic is dialectically related to each other characteristic. What this means is that curriculum cannot be defined in terms of any one of these characteristics alone; to do so risks undermining the adequacy of any outcomes or solutions we may create from our studies of the curriculum. A dialectic is a synthesis or a bringing together of opposites or poles. For instance, while it is possible for us to talk about content and method in an analytic fashion as if they were distinct, it is clear that in practice they are dialectically related. Consider the teaching of creative dance. The subject matter of creative dance has particular characteristics that are best suited to some teaching methods rather than others, like a "guided-discovery" approach over a "command-style". In other words, there is a dialectical relationship between the subject matter of creative dance and the methods one could reasonably employ to teach it effectively. The relationship between the three characteristics of the curriculum work in the same way. They are mutually dependent on each other to the extent that to remove one characteristic would result in a dangerously distorted idea of what curriculum is. To put this another way, the term curriculum doesn't "make sense", in relation to the phenomena to which it refers, if one of these elements is missing. Moreover, Carr and Kemmis (1983) point out that in a dialectical relationship

The complementarity of the elements is dynamic: it is a kind of tension, not a static confrontation between two poles. In the dialectical approach, the elements are regarded as mutually constitutive, not separate or distinct.

(Carr and Kemmis, 1983, p.37)

The implications of this point are of crucial importance, for what this dynamic interrelationship means is that we can only gain an adequate understanding of curriculum problems and issues, and propose workable solutions, when we consider how knowledge is mediated, adapted, altered and made meaningful through the interactions of teachers and learners. At the same time, we also need to consider how these interactions are shaped and formed by schools as institutions and by the purposes schools are intended to serve in the community ...