![]()

Introduction: Japan at an inflection point

Mark Metzler

Department of History, B7000, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX 78712, USA

Japan, inadvertently, has become the outstanding forerunner in a new set of global developments that can be described under the three headings of deflation, downsizing. and demography. New 'lessons from Japan' are to be discovered here, and these are not only admonitory ones. Far from it. for recent Japanese practice exemplifies the new 'choose and focus' strategies that can make an era of general, quantitative business slowdown into one of remarkable sectoral and qualitative development. The implications touch upon wide domains of activity, particularly strategic planning and finance. This introduction surveys some relevant and under-appreciated features of this recent history, in order to understand and project a few main lines of present and nearfuture developments in connection with the contributions that make up this special issue.

Introduction

In twenty years retrospect, the significance of Japan's great bubble and its deflationary aftermath seems only to grow. Its multiple implications, mostly not perceived at the time, appear in increasingly many social and economic dimensions. Two deserve special notice here. First, deflation is back in Japan, and it now seems that it never really went away. Not only that: historically speaking, this is the longest-lasting deflationary trend period in a very long time. Depending how one views it, Japan's deflation has nearly equalled or surpassed in duration the deflation that affected the Western countries in the so-called 'Great Depression' of 1873-1896. In the stream of Japan's own history, even more strikingly, this is the longest deflationary trend period since the days of the Tokugawa shogunate (Metzler 1994, Iwasaki 1996).

Second, great bubbles are now, manifestly, a global enterprise. We have only begun to perceive their wider effects. In this domain of experience, Japan got there first, and the lessons learned by Japanese businesses under deflation are worth some judicious attention from the rest of the world.

This special issue brings together a collection of studies that consider developments in the world of Japanese enterprise today and in the recent-historical sweep of the years since the deflation of the great bubble. This introduction provides a framework and contextualization for thinking about these developments, surveying, by reference to the contributions to this issue, some basic aspects of the new situation in Japan and the nature of some of the business responses that have come out of it.

The 'three Ds', post-bubble deflation, corporate downsizing, and shrinking-population demography, have come together over the past two decades in a mutually reinforcing way. These considerations are all conditioned by the great slowdown of economic growth. They raise broad and deep questions, for Japan faces a great turning point in reconceptualizing growth. And not only Japan. These questions touch on the conduct and finance of business, revealing some unforeseen liabilities and some unexpected sources of advantage in the new environment.

The age of deflation

The appearance of deflation in Japan has been epoch-making, as Japan in the 1990s underwent the first extended period of price deflation, anywhere in the world, since the Great Depression of the 1930s. Very short-term deflations occurred in early post-war Japan, in 1949-1950 and in 1953. Since then, the word had been applied rather to deflation policies, whose effects stopped short of bringing actual price deflation. Thus, by 1990, price deflation was no longer in the lived experience of any but the oldest of the current generation of policy-makers and entrepreneurs; people did not really remember what it was.

Deflation is frequently mistakenly treated, for example in the Japanese government's 2007 Economic and Fiscal White Paper, as a phenomenon that began with the Asian economic crisis of 1997-1998. Yet general deflation in consumer prices first appeared two years before that, in 1995. Consumer-price deflation was then interrupted by the fleeting economic recovery of 1996, and thereafter persisted as a trend from 1998 to the present, notwithstanding a slight and fleeting pick-up of prices between 2006-2008. Overall, consumer prices in 2010 stand at the same level that they stood 18 years before, in 1992.

If one looks instead at the GDP deflator, which incorporates wholesale prices, deflation began earlier, in 1994, and continued from then until the present. Where the consumer price index has been practically flat, the GDP deflator has fallen 14% over the period.

If one looks at asset prices, the deflation began still earlier. The deflation of share prices ran from 1990-2003. Share prices recovered from then until 2007, and fell back sharply again after mid 2007. The deflation of urban land prices ran from 1991 to the present. As of the end of 2010, both share prices and land prices remain, respectively, some 75% and 60% below their peaks of 1990-1991. Commercial land prices in the largest urban areas, after a temporarily strong recovery in 2006-2008, are now 85% off of their bubble-era peak (Statistics Bureau 2011).

The course of wholesale prices may be even more significant and has been much less heralded. Here, deflation began before the bubble, in late 1982, and became substantial in 1985, with the great appreciation of the yen and the international collapse of prices for petroleum and other commodities. The domestic bubble (that is, the great run-up of asset prices) at the end of the 1980s temporarily masked this underlying deflationary movement, which by this measure has, as of writing this, persisted as a tendency for 28 years.

The macro-level environment

More care is also needed in describing the period since the bubble, which continues to be frequently and inaccurately described as if it were one undifferentiated period of stagnation. The 'lost decade' of the 1990s, as introduced by W. Miles Fletcher's (2012) contribution to this issue, was itself contoured by three successive recessions, beginning respectively in 1991, 1997, and 2000. Each recession culminated in an acute financial crisis, followed by an interval of recovery.

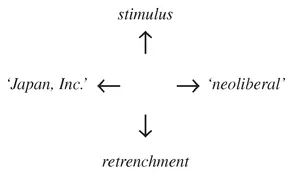

These downs and ups of the business cycle were connected to swings in policy, seen conspicuously in two dimensions. First, there was a stop-go cycle of fiscal retrenchment versus Keynesian stimulus. Second, a series of drives for 'neoliberal' regulatory reform along Anglo-US lines cycled with renewed efforts to maintain more protective 'Japan, Inc.' style arrangements (Metzler 2008). One could diagram this policy space in two dimensions as follows:1 In practice, policy combinations in the 1990s tended to cycle between the 'northwest' (stimulus/Japan, Inc.) quadrant and the 'southeast' (retrenchment/neoliberal) quadrant of this policy space.

Through each of the three stages of recession, deflation tended to intensify. The core bad-debt crisis in the banking sector grew worse, culminating in severe banking crises in 1997-1998 and again around 2003. Out of the latter crisis emerged the mega-banks, the products of repeated mergers. The banks were supported to a critical extent by massive infusions of central bank and governmental funding. At this point, policy also shifted into the 'northeast' quadrant, that is, combining neoliberal structural reform and massive credit creation, which was now directed above all to the rescue and consolidation of the banks themselves.

Even before this final round of banking crisis, there began the long-slow recovery that continued until 2006, the longest economic expansion in the whole post-war record (if also the most modestly paced one). The nature of this recovery is analysed from multiple dimensions by Ulrike Schaede (2008, 2012), whose book is one of the most important contributions to the study of Japanese business to appear in many years. Indeed, Schaede describes a new world of Japanese business. With the collapse of the Western economic bubble in 2007-2008 came renewed recession and deflation in Japan - but this time without a financial crisis. Indeed, though the magnitude of the shock was extreme, Japanese enterprise seemed relatively accustomed to the new situation.

The response of the business world

The 'business world' - zaikai - has a particular meaning in Japanese, referring to the politically organized peak business organizations, of which the Federation of Economic Organizations (Keidanren) forms the umbrella group. Bank consolidation is a classic response to depression, seen in many times and places. This financial consolidation happened within the larger context of the reorganization of the old keiretsu business groups. Consolidation also happened at the level of the zaikai itself, with the amalgamation of Keidanren with the Japan Federation of Employers' Associations (Nikkeiren) into Nippon Keidanren in 2002.

Throughout the long slowdown, Keidanren pushed for regulatory easing, which they said would liberate the energy, flexibility, and creativity of the private sector. Miles Fletcher (2012), in this issue, explicates this movement, continuing his ongoing longitudinal study of peak business organizations in Japan, which extends back to the country's primary industrialization phase in the late nineteenth century (Fletcher 1989, 1996, 1998, 2000, 2005). Prior work by two other contributors to this issue. Peter von Staden (2008) and Ukike Schaede (2000), also contributes to this study of zciikai organization over the very long run. Fletcher's timely extension of this work focuses on a question that seems likely to grow in importance, as Keidanren displays the ambition to articulate big strategic visions in the way that the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) and other government agencies are accustomed to doing. However, in this case, we also see a pattern of inflexibility and adherence to outmoded world-models similar to that diagnosed by Malcolm Warner (2011) and in this issue by Peter von Staden (2012), a perspective that blinded business leaders to the new situation and ended up contributing to the systemic impasse.

A schema in two dimensions of the national policy space was offered above. One can also consider Keidanren's own internal policy field, which shifted in response to its environmental circumstances. This is a question of the internal balance of forces within the Keidanren and of the main competing standpoints vying for representation. Here as in the larger political world, there has been a tension between a stimulus-oriented policy and a retrenchment-oriented policy. For example, Keidanren representatives called for stimulus in 1991 and 1992, as did officials of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP). They then remrned to calling for retrenchment in 1996, as, simultaneously, did LDP officials.

One sees here also the contradictions between stated goals, appearing most plainly when Keidanren representatives call, on one hand, for restraining labour costs and increasing the consumption tax - both tending to suppress domestic demand - while calling on the other hand for 'expanding the domestic market'. How does one have it both ways? In Japan, the conventional way out is by means of massive industrial investment, which has historically constituted an extraordinarily large share of total domestic demand. But with investment demand maxed out as a result of bubble-era over-investment and low growth, and with mountains of private debt looming on all sides, where was new demand to come from? In practice, it has come from the other source on which Japanese business had grown to rely, overseas demand. In the early twenty-first century, the new demand was above all from China.

Has Keidanren been a force for innovation or a source of inertia? Certainly Keidanren representatives sounded radical, even Marxist in talking about the way that old practices (meaning in practice the regulatory system) were 'shackles' on the forces of production. Peter von Staden (2012), in this issue, also considers some systemic ideological 'fetters of the past', in an ambitious and theoretical account that starts with mind itself and finds its empirical grounding in a discussion of the system of business-government deliberation councils (shingikai). Like Fletcher's work, this account draws on Japanese language documentation to present a new account of events. These deliberation councils play a little noticed but pivotal role at the centre of the Japanese policy system. First, they provide inputs to the policymaking process. On the output side, they serve as channels of communication, coordination, implementation, and corrective feedback. This work also builds on a longer longitudinal study (von Staden 2008), and provides a remarkable window into core debates over social values, which are at the heart of the process that Schaede (2012) describes as a strategic inflection point.

Downsizing and upgrading

Here we come to the age of 'choose and focus' - a great shift of emphasis from prioritizing of revenues and market share during the high-growth era to a new, low-growth era priority given to profit and reconsolidation around core competencies. This can also be described as a shift from a more extensive to a more intensive mode of operation.

As Ulrike Schaede (2012) explains in her contribution to this issue, synthesized from an extraordinary range of source material and interviews, Japan has come to the end of the long post-war era and entered a new institutional era, emerging out of the so-called 'lost decade' interval. Even in the early 1990s, historians were unsure whether Japan's seemingly endless 'postwar present' could properly be treated as history (Gordon 1993). There were practical reasons for this doubt. The transformation after World War II was manifestly historic and epoch-making. But then, after the mid to late 1950s, despite enormous quantitative growth and upgrading of the Japanese economy, the basic institutional framework - and the framework of economic regulation particularly - were truly and remarkably stable. Indeed things were stable to the point of being boring, presenting little of the drama people seek in history. But that era is well past; we now speak of our own age as the post-bubble era. In the process, a system that had come to seem 'slow and unwilling to reform' in fact underwent a great wave of reform, beginning in 1998, with the great financial crisis of that year. The reform drive intensified in the early 2000s and resulted by 2006 in a comprehensive reformation of the business and legal/regulatory framework, as Schaede details. This has been accompanied by a great shift in the system of regulation from a 'parental' style of informal, actor-based bureaucratic regulation to a more rule-based, transaction-focused type of regulation.

This reformation is of the very type described in various theoretical traditions as a transformation of the 'regime of regulation', or of the 'social structure of accumulation', or of technological and organizational paradigms (Kotz et al. 1994, Jessop and Sum 2006, Freeman and Louca 2001). The differences between these various analytical schools and their political valences seem less interesting than the ...