![]()

I noticed … that whenever he spoke of serious matters, whenever he used an expression which seemed to imply a definite opinion upon some important subject, he would take care to isolate, to sterilise it by using a special intonation, mechanical and ironic, as though he had put the phrase or word between inverted commas, and was anxious to disclaim any personal responsibility for it … (Marcel Proust, Remembrance of Things Past, vol. I, p. 74)

‘The Duchess, as Swann calls her,’ she added ironically, with a smile which proved that she was merely quoting, and would not, herself, accept the least responsibility for a classification so puerile and obscure. (Ibid., pp. 203–4)

Chapter 1

The expression of subjectivity and the sentences of direct and indirect speech

Among the various acts and events which language may report, it has developed special linguistic forms for reporting the act of utterance itself. It is through these reflexive forms of reporting speech that language reveals its different functions. The expressive and communicative functions can be isolated because the speaking subject and his utterance become, not merely the transparent vehicle of expression1 and communication, but the object of a self-conscious attention on the part of language turned back upon itself.

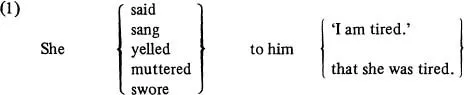

Their status as an apparent report of a linguistic communication is conferred on both direct and indirect speech by a related, adjacent clause containing a verb of saying – the verbum dicendi of classical grammar – whose deep structure subject refers to the quoted speaker and whose indirect object to his addressee/hearer. Partee (1973a, p. 325) calls this class of verbs ‘verbs of communication.’ They include verbs like say, ask, request, command, declare, confess, advise, insist, claim, shout, read, sing, remark, observe, note, yell, swear, promise, announce and pray. The communication verb is characterized, not just semantically, but also syntactically, by its ability to take an indirect object referring to the addressee/hearer:2

The communication paradigm including a speaker and hearer is thus reflected in the syntax. While all verbs subcategorized to take an optional indirect object are not communication verbs, not meeting the semantic requirement of signifying an act of linguistic communication (for instance, the verb give), any verb which cannot take an indirect object thereby does not fit the speaker–addressee/hearer paradigm.

(2) | * | I wondered to you if the train would be late. |

| * | John realized to Mary that he was wrong. |

Direct and indirect speech often paraphrase one another: ‘Mary said, “I am tired”’ and ‘Mary said that she was tired.’ But, despite their apparent synonymy, what is reported of the original speech is not necessarily the same in both. Because, as we shall see, the communicative and expressive functions are not represented in the clause of indirect speech, they can be shown to be independent of language per se. For it is in the syntactic differences between direct and indirect speech that we find the evidence allowing us to formulate the rules and principles of the syntax for expressing subjectivity. Because these are not ‘given as the data is given,’ our route lies through syntactic argumentation.

We begin by observing the similarities and differences between both forms and then proceed to consider possible hypotheses for explaining them. The most obvious one suggested by Chomskyan theory is to posit a transformational relation between the two. Within the framework of generative grammar with its division between two kinds of rules or formal operations, base rules and transformations, this means that direct and indirect speech would share a common ‘deep structure,’ one form very plausibly (but not necessarily) furnishing the deep structure for the other. This is the case, for instance, for the pair ‘Did John go?’ and ‘John did go,’ where the first is held to be derived from the second by a movement transformation. The deep structure level is not to be construed as equivalent to the level of semantic interpretation but as a syntactic level whose structures are generated by rules assigning the syntactic formatives to grammatical categories such as ‘sentence’ and ‘noun phrase.’ These are the ‘phrase structure rules’ of the base component. At one stage the ‘standard theory’ assumed that all meaning was interpreted at the level of deep structure, but since then the ‘extended standard theory’ sees different aspects of meaning ‘read off’ the different syntactic levels. Hence, paraphrases like ‘Mary said, “I am tired”’ and ‘Mary said that she was tired’ can be explained in terms of a transformational relation only if independent syntactic arguments can be found justifying the transformational solution. Otherwise, their synonymy must be accounted for in some different way. Synonymy is not a sufficient argument for a transformational relation; there is no a priori reason why two paraphrases cannot have two different deep structures. The question is an empirical one.3

The evidence provided here leads us to discard the transformational solution for reported speech. This should be taken, however, as an argument against the need for a transformational component in the grammar.4 Once having accepted the necessity for transformations, it becomes an empirical issue which constructions are ‘base’ generated – i.e. generated in deep structure – and which are ‘derived,’ and ultimately, what is the form of the two components. It is through arguments against the transformational solution for reported speech that we will be led to a revision of the base rules, enabling us to give a general account of expressive constructions within the extended standard theory. Th...