- 238 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Organization and Marketing (RLE Marketing)

About this book

Taking as its starting point the nature of marketing tasks, this book draws on organizational theories and makes its own contribution to generate insights and understanding about some of the concerns that need to be deal with if marketing success is to be achieved. The book surveys developments in the study of organizations, and considers how organizations can be adapted to better serve the needs of marketing.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Organization and Marketing (RLE Marketing) by Peter Spillard in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

THE TASKS OF MARKETING

Introduction

Marketing, as one sage put it, is concerned with making it easy and profitable for potential customers to do business. While this definition has superficial appeal and would probably go down well at the annual sales convention, it provides only a partial view of the complex nature of the marketing task. Even Kotler’s definition that it is “a social process by which individuals and groups obtain what they need and want through creating and exchanging products and value with others”1 lacks any understanding of the feel for what constitutes that process or how it varies from context to context.

Yet if any sense is to be made of the relationship that exists between the way an organization is structured and the objectives which people in that organization have set themselves in the market-place, then at the same time an attempt must be made to identify the essential tasks of marketing. It is also necessary to plot the variations in those tasks that might exist over time and space. Only then does it become possible to begin to link organizational choices with marketing activities.

The correct design of the organization for marketing which unites the disparate needs of the total enterprise, the people within it and the tasks which confront it and which at the same time provides scope for adaptation as things change over time, is one of the most important strategic decisions confronting senior management. Since an organization is a mechanism for getting things done, it follows that what needs to be done may form a major input conditioning the final choice that is made. This chapter therefore examines the major dimensions of the marketing task as it may be defined in a variety of situations that an enterprise might face over its lifetime.

Kotler’s Typology of Marketing Tasks

Before leaving Kotler, though, it is worth recalling what he has to say about the marketing task in his text.

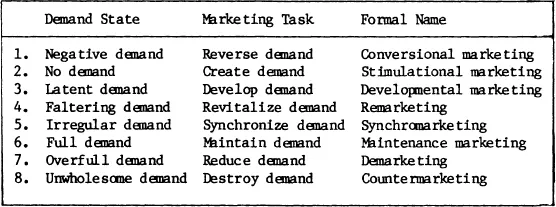

Stemming from his definition of marketing management as “the analysis, planning, implementation and control of programs designed to create, build and maintain mutually beneficial exchanges and relationships with target markets for the purpose of achieving organizational objectives”, Kotler states that one of the tasks of marketing management is to regulate “the level, timing and character of demand”. He constructs a table, reproduced below, and elaborates each of the eight different classes of marketing task that result from a typology based upon demand states2

Figure 1.1: Kotler’s Classification of Basic Marketing Tasks

• Conversional Marketing has the task of converting antipathy towards a product to a liking for it. The task confronting a tour operator with a franchise in a politically troubled area of the world where violence has broken out would be a case in point.

• Stimulational Marketing is not quite as difficult a task since it involves merely creating wants or intentions to purchase by turning apathy into action. Apathy, in this sense, can be caused by ignorance, irrelevance of an appeal, or a scale of values that places the acquisition of the product low down the list of priorities.

• Developmental Marketing is still less difficult because the task is merely one of providing easy access to a new product for which a need and a want exist and which faces no serious competition.

• Remarketing involves rejuvenating and revitalising existing demand for a product by relaunching, reformulation and imaginative remedial programmes designed to restore popularity to previous levels.

• Synchromarketing merely means that there exists a task of retiming demand to, for instance, even out troughs and peaks or to create demand only during times or in places where the product is available for purchase. This is particularly important in the marketing of services because services cannot by their nature be stored.

• Maintenance marketing, perhaps the easiest of all tasks confronting the marketing manager, involves merely the effective maintenance of the status quo. At most it implies the need for defensive measures against the predations of future competitors or other sources of threat. It also necessitates the running of an efficient operation with plenty of attention being given to service, productivity and customer contact. Other than these, the only kind of innovation that assumes any importance is that involving the fine-tuning of marketing propositions to meet small changes occurring in the market-place so as to secure the maximum advantage from the strong position already enjoyed.

• Demarketing tasks arise when there is a need to cut back demand for a product. This may occur, for instance, when there are uncontrollable shortages of supply. Maybe existing levels of demand place too much strain on limited resources. The Location of Offices Bureau was one manifestation of this when a few years ago London as a commercial centre was being demarketed in favour of the Provinces. This was because of the social and economic pressures being created in the Capital by too much commercial property development.

• Countermarketing involves actually destroying demand, perhaps because of the harmful effect some products are suddenly found to have. Blue asbestos, high tar cigarettes, sniffable glue and certain harmful agrichemicals provide recent UK examples of these.

Now it is quite possible, of course, that a firm may be marketing a range of products each designed for a particular and differing market and facing a variety of competitive environments. To say therefore that the tasks in Kotler’s terms facing a product are synonymous with those facing an entire enterprise is true only of the single-product firm. Most firms do not fall into this limiting category and therefore have to set up their marketing organization to cope with contexts that may, over a period of time, contain elements of all eight of Kotler’s tasks. The problem is made particularly difficult because each of the tasks requires a specific organizational treatment if it is to be performed well. The mix between efficiency and creativity as determinants of success varies considerably between, say, stimulational marketing and maintenance marketing.

Since it is likely that the mix of tasks will fluctuate more than the organizational variables can afford to, it follows that marketing organization has to be able to cope with most of them either at the same time or in quick succession. Any structure is therefore unlikely to be for very long orientated to any single one of the tasks, especially since in a sense the various types that Kotler identifies are stages in a life cycle of tasks that follows closely the cycle of products or markets. If an organization were so orientated then if structure is at all linked to purpose, it would have to change radically moment by moment. Clearly, then, there is a trade-off between the ‘fit’ of a structure with its current tasks and the disturbance caused by constant organizational change made necessary if a perfect match between task and structure is always to be attained. Kotler’s typology, however useful it may be for assisting an understanding of marketing tactics, is not of very great help in contributing to one of strategic organization therefore.

Khandwalla’s Classification of Marketing Tasks

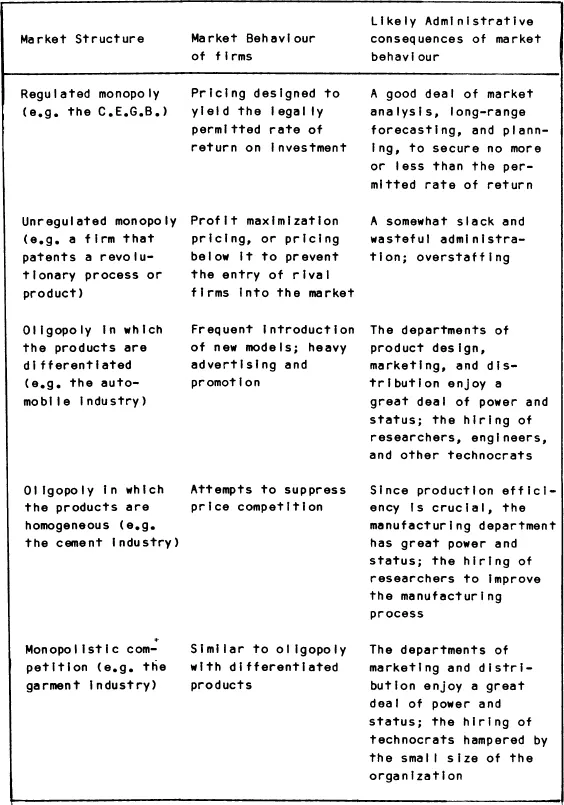

Khandwalla3 provides a classification of marketing tasks based upon the rather more permanent dimension of market structure than merely that of product context. He borrows the traditional classification of the economists when he constructs his table (reproduced below) plotting the linkage between structure, market behaviour and administrative consequences. Notice the differing degree in which marketing features with each type of market structure and how Khandwalla by implication introduces the idea of a “leading function”, different according to circumstances existing in the environment.

Figure 1.2: Khandwalla’s Classification

Source: Khandwalla P. N. (1977) p.48–9.

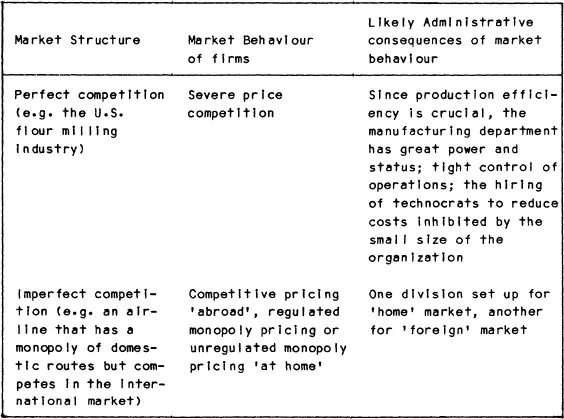

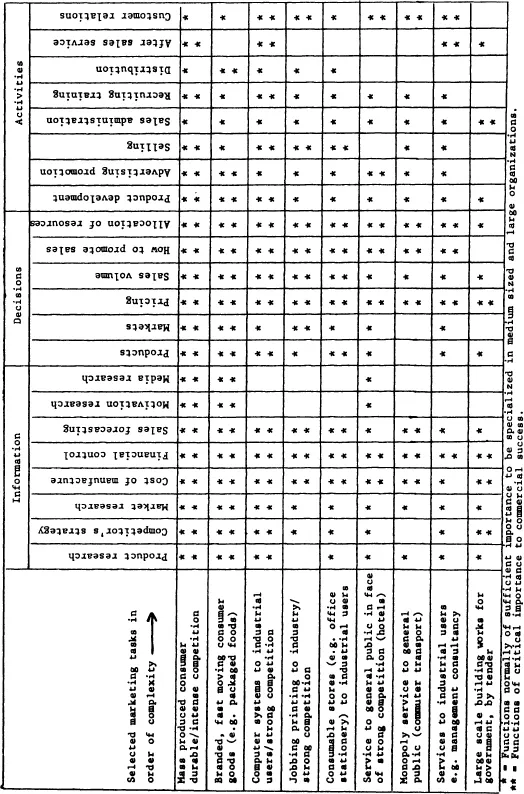

Sadler’s Classification

Sadler4 (see over) depicts yet another way to derive connections between marketing and organization when he builds his table. This table has the benefit, at least, of showing one expert’s beliefs about the various task priorities facing a firm in differing product/market contexts and how their nature and complexity vary.

Task Conditioned by an Organization’s Intentions

Complexity of task, however, is not merely a function of the type of product or the market context alone. It is also determined by what the enterprise itself wishes to do in relation to what it at present is doing. In other words, the policy and strategic objectives themselves can be causes of differences in task between firms marketing similar products to identical markets.

To this extent none of the authorities already quoted provides the full picture. It is almost as if there is an assumption behind their thinking that somehow marketing tasks are “givens”, determined by exogenous factors alone. Quite apart from tasks differing depending upon the state of development of marketing activities within an organization (some of these activities may be sophisticated and some merely embryonic, thus implying vastly differing problems which must be confronted), they also differ according to what kind of impact the people in the firm wish to make upon the market. This is one reason why it is possible to find different structural solutions adopted by firms even when they face identical market conditions – an idea not present in any of the schema so far mentioned, except, in a limited way, Kotler’s. A policy of growth, innovation and aggressive penetration of a new market via radical new ventures will clearly generate a fundamentally different set of problems and tasks from one aimed at stability, consolidation and the arrangement of the laurels on which to rest. A firm aggressively aiming to penetrate a market will be creating complexity; although it will do so within its own capacity for handling the risks involved. One aiming to stay in a dominant position may do so by creating, in a sense, its own environment. It will aim to simplify a complex market, perhaps by being selective in dealing only with standard mass-demand products and intentionally ignoring technologically risky ventures, protecting itself by deploying its power over resources, channels and even new ideas or practices. Gaining power, then, means taking risks; maintaining it means eliminating them. In the first instance uncertainty is sought and in the latter it is suppressed.

Figure 1.3: Sadler’s Task Characteristics of Different Marketing Situations

The rate of strategic and tactical change itself affects the nature of the marketing task too. A rapid transition from complacency to aggressiveness in the market-place, made necessary by circumstances or caused by a new sense of mission perhaps, presents a different set of problems to overcome, both inside and outside the firm, than a slower rate of change. The first may require some revolutionary action; the latter can afford the luxury of evolutionary adaptation. At the very least while the change is taking place – especially in service industries that cannot possibly afford a partial shut-down – existing business cannot afford to be lost. This means that the new and the old tasks have to be performed in parallel for some time. A separate division, a new subsidiary, or at least a temporary venture group, team or product group may be called for when change needs to be rapid and when there is therefore no possibility of quickly and effectively restructuring the entire enterprise. A “bolt-on” solution may be the best one in the circumstances.

Slower change can mean that existing business or markets can be phased out to be replaced gradually by the new venture. It also means that there is time for organizational adaptation through personnel changes, organizational development, training and non-traumatic alterations to structure. Bureaucratic systems have a better chance of surviving if change is gradual, provided of course they are capable of step by step adaptation and do not become so rigid that change when it is finally needed brings disintegration. Survival, then, depends on the ability to contrive a revolution in organizational structure, purpose and behaviour without at the same time any loss of performance – a fairly difficult task.

Links Between Strategy and Task: Porter’s Ideas

Independent of the rate of change, Porter5 helps us to understand how the three generic strategies of

• overall cost leadership;

• differentiation and

• focus

influence the requirements imposed upon the organization.

By “cost leadership” Porter means the unrelenting struggle for securing competitiveness through economies of scale, programmes of cost-reduction, and the ruthless elimination of unprofitable activities, customers and markets. By “differentiation” he means the search for uniqueness through the development of marketing propositions that provide value to a market in ways more acceptable than those provided by competitors offering substitutes. And by “focus” Porter means the concentration on a particular market segment. He might also have included within his definition of focus the concentration upon a particular “logic” – a concept elaborated upon later in this book.

Having established his terms and his classification, Porter then produces the following table (Figure 1.4).

Column three of the table clearly displays the requirements that each of the three generic strategies lays at the door of the organization when planning and taking action. Whether in practice it is ever possible for a firm’s strategy to be as singular as Porter implies is very doubtful; in many cases firms adopt all three types of st...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 The Tasks of Marketing

- Chapter 2 Organizational Choices

- Chapter 3 The Contingencies

- Chapter 4 The Logics of Organizations

- Chapter 5 Conflict and Integration in Marketing

- Index