![]()

Chapter 1

Dendrochronology: an Outline History

There can be little doubt that dendrochronology as a science owes its present level of development to the efforts of A.E. Douglass in the early decades of this century. However, over the years a number of authors have busied themselves searching out examples of the use of tree-rings in the era before Douglass’s classic work. Their findings indicate numerous references to the existence of rings in trees, the observation that trees record climate and the observation that trees exhibit similar ring patterns. In addition, several early authors are credited with postulating cross-dating. What is clear, however, is that it remained for Douglass to exploit the method, to establish its techniques and procedures and to build the first long chronologies which are the backbone of the science. In the sections which follow scant attention is given to the ‘early’ workers by comparison with that devoted to Douglass.

Early References to Tree-rings

There is an old saying to the effect that there is nothing new under the sun. Most breakthroughs in science have built on earlier ideas, on someone else’s work or previous failures. Not surprisingly, it was no different with dendrochronology and in what follows no apology is made for the blatant use of secondary sources.

It takes no great stretch of the imagination to accept that Theophrastus, a student of Aristotle, knew that fresh growth formed on the outer circumference of a tree (Studhalter, 1956, 32). Anyone seeing a stone surrounded by the folds of a living tree could have jumped to the same conclusion, whether he was Greek, Egyptian or Palaeolithic. It is certainly no surprise to read that Leonardo da Vinci had recognised the annual character of tree-rings, nor that he had deduced a relationship between ring width (for a given year) and moisture availability, to allow a weather reconstruction (Stallings, 1937, 27).

However, if Leonardo did all that, then Duhamel and Buffon, Linnaeus and Burgsdorf were positively unoriginal when in the eighteenth century they variously counted back to the ring of 1708–9 and noted severe frost injury associated with that same severe winter (Studhalter, 1956, 33). Numbers of people in the early nineteenth century appear to have been noting the similarities between ring patterns of trees cut at the same time. Studhalter champions Twining as someone who was cross-dating as early as 1827. Zeuner (1958, 400) plumps for Babbage describing cross-dating in 1837, and indeed Babbage did appear to be getting to the heart of the matter when he predicted ‘the application of these views [cross-dating] to ascertaining the age of submerged forests, as to that of peat mosses, may possibly connect them ultimately with the chronology of man’. Here is someone obviously talking about the real-life nitty-gritty of dendrochronology – namely the extension of a chronology back in time by the overlapping of successively older ring patterns. If one is looking for a name to put before Douglass in a list of dendrochronologists, then that name might as well be Babbage.

Douglass and the Early Work

Douglass did not come to tree-rings with the idea of developing a dating method for archaeologists. At the beginning of the twentieth century he was working at the Lowell Observatory at Flagstaff, Arizona. His interest lay in the relationship between solar activity and earth climate. One question, for example, concerned the various cycles observed in the sunspot numbers. Could these cycles be paralleled by cyclic phenomena in climate? Obviously if some causal relationship could be established and if the cycles in solar activity could be proven to be stable, the opportunity would have existed for the prediction of climate. The snag at the time was that while records of solar activity extended back for centuries, the records of climate were extremely short in the area in which Douglass was working. In any study of cycles it is important that the overall record be much longer than the duration of the individual cycles being observed. There would be little point in looking for proof of an eleven-year cycle (the sun-spot cycle in round figures) in a ten-year series of weather observations. In order to get around this problem Douglass addressed himself to the extension of the available weather record by the use of proxy data – tree-ring records. In the American south-west large areas are what could be termed semi-arid. In such an area the growth of trees is highly dependent on the amount of available moisture, mostly rainfall. Therefore the year-to-year variations in ring width should reflect the year-to-year variations in rainfall; narrow rings being the product of drought.

Since trees grow to considerable ages it seemed possible that long records of rainfall could be reconstructed. Observation of the ring patterns of yellow pine (Pinus ponderosa) showed that in addition to the year-to-year variations in ring width there were trends towards wider or narrower rings over periods of years. These longer-term trends could be clearly seen when the year-to-year detail was removed by smoothing the curves.1 Since the year-to-year variations were due to rainfall the longer-term trends must have been due to some other factor. Since in the south-west the number of hours of sunshine per year would be essentially constant, the long-term variations must be due to variations in solar activity. With this reasoning as a background, Douglass embarked on a study of cycles in tree-rings which was to engross him for most of his life. However, cycles are not the concern of the present writer. More important by far were the developments which were to take place in the study of tree-rings as a result of Douglass’s attempts to extend his proxy data records. Ultimately this led to the development of dendrochronology as a science.

Interestingly, the term dendrochronology does not make its appearance until considerably later. Douglass, in referring to the measurement of time by means of a slow-geared clock within the trees, i.e. the slow formation of rings, states that ‘the term dendrochronology has been suggested as a coverall for tree-ring studies’ (Douglass, 1928, 5). It is in this sense that it is currently used to describe the cross-dating of wood samples.

The first move towards the study of long proxy weather records involved the collection of samples from living or recently felled trees. It was important that the ring patterns should be firmly anchored in time and the simplest way to ensure this was to know the date of formation of the outermost growth ring. By 1909 the ring width patterns of a group of 25 pines were available. These were presented in print without being cross-identified, i.e. no check had been made to ensure that the ring patterns stayed in phase; an important factor in trees which could miss rings in years of extreme hardship. The value of cross-identification was apparently not recognised until 1911 (Douglass, 1919, 24). Thereafter cross-identification showed up various errors in the ring patterns and a tidied version was produced. By 1919 the chronology covered the period AD 1382 to 1910 (for yellow pine in the Flagstaff area).

The longest-lived yellow pines available to Douglass were limited to around 500 years. In order to investigate cycles and climatic factors over longer periods he began, around 1915, to take an interest in the giant redwoods of California (Sequoia gigantea). While these trees exhibited a much less specific response to climate, this was more than compensated for by their considerable life spans. However, although of great age, up to 2,000 or 3,000 years, not all of the available trees were usable and there were a number of problem rings. By 1918 a chronology for redwoods covered 2,200 years and suitable trees were being sought to extend this record. At that time the redwoods were still being exploited for timber and samples were available as wedges cut out of the stumps. Use of large samples allowed the checking of individual rings around a considerable portion of their circumference and this in turn reduced the number of problem rings. In the 2,200-year chronology only one doubtful ring remained after cross-identification of the various individual trees. This was a possible ring ‘within’ the ring for 1580, called 1580A. In practice this meant that in a number of trees the ring for the year 1580 included what might have been an additional ring, though in no case was this extra ring definitively present. A further sample collection trip in 1919 resolved the problem and showed conclusively that 1580A did exist. Thus 1580A was positively identified as the ring for 1580 and all of the older sections of the chronology had to be renumbered to one year earlier. By 1919 a redwood chronology of 3,221 years had been produced.

Archaeological Extension of the Yellow-pine Chronology

Both of the above chronologies could be called long modern chronologies. Their construction had required little in the way of extension by cross-dating since they were composed almost exclusively of recently felled trees. By 1923 renewed interest in the Flagstaff yellow-pine chronology yielded an extension back from 1382 to 1284. This appeared to exhaust the possibilities of the living trees. To go back further in time it became necessary to study timbers from prehistoric Hopi villages and ancient ruins in the area. The semi-arid conditions were responsible for the long-term preservation of wood on these sites and the timbers could be sampled either by slicing (where appropriate) or coring.

By 1922 a floating chronology had been constructed using timbers from Aztec, New Mexico and Pueblo Bonito some 50 miles to the south. This chronology covered RD (Relative Date) 230 to RD 543, a total length of 314 years. There was no way of knowing the true age of this chronology except by joining it to the 1284 modern chronology. Since no join could be found, Douglass had to assume that RD 543 was some years older than 1284. The importance of consolidating this chronology was obvious. Once tied down in real time, the dates of these prehistoric sites could be established very accurately. In addition, the chronology available for cycle studies would be extended. The particular attraction of being able to date the archaelogical ruins seemed worth a considerable effort. In the mid-1920s Douglass (1928, 61) was able to hypothesise two ways to achieve the dating of the Aztec-Bonito complex. The first would be to bridge the gap by overlapping successively older timbers until such time as a link with the floating chronology was achieved (a procedure which is considered classic dendrochronology today). The second was by what he called ‘sequoia comparison’. Since the sequoia chronology ran continuously back to around 1200 BC it had to cover the period of the Aztec-Bonito floating chronology. The question was, could a yellow-pine chronology from New Mexico be cross-dated against a sequoia chronology from California? Douglass reckoned that the best hope had to lie with the former, the bridge method. This was on implicit recognition by him of the questionable character of tele-connection, i.e. the matching of ring patterns over very long distances (of which more later).

Cross-dating

At this stage the discussion had moved away from the study of essentially living, or at least recent trees, to the study of undated individual ring patterns. The only way to place such ring patterns in time was by cross-matching them with others. It is important to understand the concept of cross-dating as developed by Douglass. A good example of the tying down of an undated sample took place as early as 1904. Studying the ring records of a number of pines newly felled near Flagstaff in that year, Douglass noted that a group of narrow rings occurred in each tree around 1880. In particular the rings for 1880 and 1883 were very narrow. To quote Douglass (1937, 3):

While this was fresh in mind, curiosity raised the question whether this same [narrow] group could be found near the outside of a slightly weathered stump whose date of cutting was unknown. On examining the rings in the stump the group was found at once but was only eleven rings in from the outside. So that tree must have been cut in 1894. The owner of the land was sought and asked when his timber was cut and he answered, ‘in 1894’.

This is almost certainly one of the first examples of the dating of an unknown specimen by dendrochronology.

Here then was the key to the methodology behind cross-dating in the south-west. In any piece of wood to be dated, configurations of rings were sought which were known from previous work to occur over a unique set of years. For example, a set of four narrow rings followed by two wide rings with a noticeable narrow seven years later occurred over the years 1215 to 1227. A wood sample exhibiting this configuration fifteen years in from its bark surface could be assumed to have last grown in 1242. Final confirmation would be obtained by checking the remainder of its ring pattern for further extreme rings coincident with the known chronology. This same approach could be applied to substantial pieces of charred wood or charcoal from archaeological excavations, provided only that they contained sufficient numbers of rings to allow definitive matching. Douglass is attested to have retained a prodigious number of such ‘signature’ patterns in his memory with the result that he could often date archaeological samples simply by looking at their ring patterns under a lens and comparing these with his memorised chronologies.2

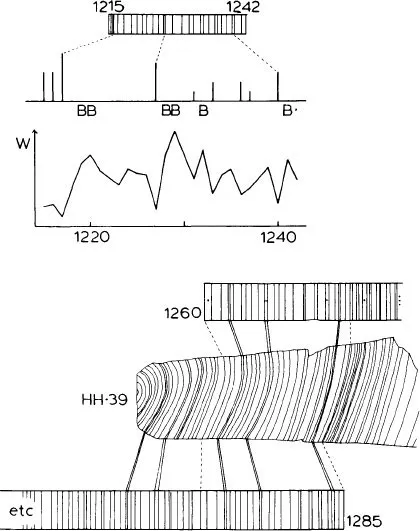

Obviously the whole programme of research was not simply carried about in Douglass’s head. In order to facilitate the recording of the patterns of rings the following scheme was devised. A horizontal scale in years was employed. Plotting from left to right, from the centre to the outside of the sample, each narrow ring was assigned a vertical line; the narrower the ring the longer the line. Very wide rings were denoted by a capital B under the horizontal line. Average rings were not marked. Figure 1.1(a) shows how the configuration for the period 1215 to 1242 appeared when plotted in this format. Because only the extreme rings were denoted, this representation became known as the skeleton plot. In practice a master scheme was created against which the skeleton plot of each new sample could be compared.

Figure 1.1: (a) Skeleton plot and graphical representation of the ring pattern for the period AD 1215 to 1242 in the American south-west, (b) How HH-39 formed the key link between Douglass’s modern and archaeological chronologies in 1929.

The First Decisive Archaeological Cross-dating

As noted above, Douglass had made the decision to attempt the absolute dating of his Aztec/Pueblo Bonito 314-year chronology by bridging to the relatively local Flagstaff yellow-pine chronology which extended back to 1284. His decision not to try tying down the floating chronology against the very long sequoia chronology was probably conditioned by both the distance between the sources and the differing climate and species responses. (If he could complete the pine chronology independently, then it could be compared at one specific position in time against the sequoia chronology. Any cross-matching found at that unique position would, if it occurred, confirm the correctness of his archaeological chronology. On the other hand, since cross-dating could not be assumed, any attempt to date the archaeological chronology directly against the sequoia chronology might well have led to a spurious result.)

The situation in which Douglass found himself was a classic one in dendrochronological terms. He had two yellow-pine chronologies whose exact relative placement in time was unknown. The floating chronology could be surmised to be older than the long modern chronology on the basis that no cross-matching could be found between them. It must be remembered that any overlap between the chronologies would have to be long enough to allow definitive cross-dating, a short overlap being no better than no overlap at all. The options in this situation were twofold. Attempts could be made to extend the modern chronology back in time to tie up with the floating chronology or vice versa.

In order to achieve one or other of these aims an expedition was sponsored by the National Geographic Society in 1923 to collect material for chronology extension. This was named the First Beam Expedition. Large numbers of beams were collected from structures of all ages. These included pueblos, historic buildings and prehistoric sites within the south-west. It was hoped that long-lived timbers from some of the early historic sources might match with and extend the modern chronology back to before 1284. Unfortunately, although many timbers could be dated against the existing chronology, none extended it significantly back in time (an analogous situation is discussed in Chapter 7). On the other hand, many early timbers were found to cross-date with the floating Aztec/Pueblo Bonito chronology. In particular, timbers from a ruin in Wupatki, north-west of Flagstaff, were tied to the floating chronology. Other timbers from this same ruin formed the basis of a second floating chronology. Importantly, on the basis of accumulated pottery evidence from the various cross-dated sites, this second chronology of approximately 140 years could be placed later than that from Aztec/Pueblo Bonito, i.e. between it and the modern chronology. To quote from a recent review by Robinson (1976, 11):

As analyses proceeded on the collections made by the First Beam Expedition, more and more specimens gradually yielded to cross-dating within one or other of the two relative chronologies. These two were ultimately merged, in 1928, to form a single chronology of prehistoric ruins with a length of 585 years. The status, then, of chronology building early in 1928 consisted of two long records. The absolute chronology extended from the present back to about 1400 with confidence, and weakly – because it was based on few trees – to about 1300 [in fact to 1284]. The other was a floating chronology o...