![]()

Part I

Perspective matters

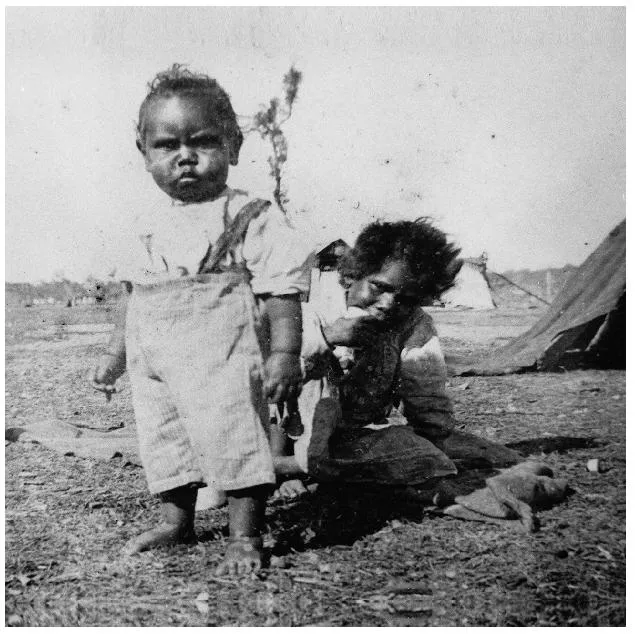

Figure I Children at Barambah Aboriginal Settlement, c. 1905. State Library of Queensland Neg: 112322.

![]()

Chapter 1

“Come this way”

Research with children

Child-environment researchers span a number of disciplines, often applying an inter- or trans-disciplinary perspective across the arts, sciences, humanities, and social sciences. This body of work is central to this ethnographic study, and a brief literature overview is provided. The fields of architecture, environmental psychology, ecological psychology, and, in part, anthropology have informed the transdisciplinary perspective taken in this study on Aboriginal children and their local environment. In this chapter, I illustrate that transactionally orientated research is in many ways congruent with transdisciplinary research, supports holistic investigations into people-environment relationships, and informs and guides specific theoretical approaches. A convergent approach applied throughout this study is the functional approach, which is particularly relevant to ecological psychology and can add theoretical rigor and direction to the exploration of children’s environmental place use and experiences. In light of these “place” considerations, I propose a “transactional framework of place” that defines place within the person-environment relationship. The methodological considerations that correspond to these transdisciplinary and broad theoretical perspectives emphasise the development of an academically and practically orientated methodology that takes into account the numerous challenges of engaging and interacting with Indigenous children.

The environment and its children

The literature on children and the environment is an inter- and trans-disciplinary area of study. It covers a variety of disciplines, ranging from psychology, sociology, geography, education, and health to planning and design fields. This brief literature review focuses on those areas of research most relevant to this study on children and their physical surroundings and draws primarily from environmental psychology, only briefly mentioning other disciplinary areas where relevant. In addition to this literature overview on children and the environment, further pertinent literature is presented at the beginning of each of the following chapters.

Research interest into children’s environments among environmental psychologists was first made widely known by Altman and Wohlwill’s (1978) book on Children and the environment and more recently in a special issue of the Journal of Environmental Psychology, 22(1–2) (2002), on children and the environment. This international research interest is illuminated in the Children, Youth and Environments Journal and continues to be supported by special network groups at the Environmental Design Research Association (EDRA) and International Association for People and Environment Studies (IAPS). Complementing this growing body of research in environmental psychology is the area of children’s geographies (Aitken, 2001; Holloway & Valentine, 2000; Matthews, 2003), and the related field of environmental education (Blizard & Schuster, 2007; Catling & Willy, 2009; Murtagh & Murphy, 2011; Pike, 2011).

Psychological research on children is dominated by developmental psychology. This gained momentum with Piaget and Inhelder’s (1956) formative study in which they located distinct periods of child development in relation to space conception. Since then, child and developmental psychologists have expanded the field, taking into account molar, molecular, and cross-cultural environments (see Lerner & Damon, 2006; Valsiner, 1989; Valsiner & Connolly, 2003). Relevant to environmental psychology is the work of environmental and developmental psychologist Gary Evans (2006) who studies the physical properties and conditions of the environment in relation to children’s health, well-being, and development. He discusses behavioural toxicology, noise, crowding, environmental chaos, housing and neighbourhood quality, and schools and day-care centres. The scholar Gary Moore (1983, 1986), with degrees in architecture and psychology, considers how physical surroundings affect children’s healthy development. Focusing on children’s play settings, Moore discusses how particular environmental features promote social, cognitive, and motor development. He argues that traditional playgrounds promote motor development, but are unsupportive of cognitive and social development because they offer limited unstructured and spontaneous play opportunities. The importance of play for children’s healthy development is emphasised by a number of more recent publications (e.g. Brown, 2009; Hughes, 2010; Wenner, 2009).

There is a growing concern among researchers that children’s developmental needs are not being met within western contemporary contexts. This has spurred an abundance of studies on children in their urban environment (e.g. Camstra, 1997; Hillman, 1997; O’Brien, Jones, & Sloan, 2000). A concern for children’s diminishing opportunities for independent play in outdoor settings was raised more than a decade ago by Hillman (1997) and continues to be a marked concern for researchers (e.g. Francis & Lorenzo, 2006; Kernan, 2010; Spencer & Woolley, 2000). The decline in outdoor and free play is partially due to the interplay of legislative, social, technological, pedagogical, and urban design factors (Clements, 2004; Francis & Lorenzo, 2006; Waller, Sandseter, Wyver, Ärlemalm-Hagser, & Maynard, 2010, resulting in less time spent in natural settings (Faber Taylor, Kuo, & Sullivan, 2002; Moore & Marcus, 2008). Research has shown that nature contact has developmental benefits for children, which is linked to positive behaviours and attitudes towards nature later in adult life (e.g. Chawla, 1988, 1998, 2007; Evans, Juen, Corral-Verdugo, Corraliza & Kaiser, 2007; Kahn & Kellert, 2002). This has led to a recent surge in research advocating for sustainability education that fosters a willingness to protect, preserve, and care for the natural environment (Chen-Hsuan Cheng & Monroe, 2010; Kong, 2000; Moore, 2007).

Children’s declining opportunities for independent exploration in many western countries has resulted in continuous interest in children’s exploration and mobility range in both rural and urban settings (e.g. Chawla, 2002; Lynch, 1977; Matthews, 1992; Prezza, 2007; Tranter & Pawson, 2001). Independently exploring the environment is especially important in middle childhood, during which time children display the greatest territorial range and autonomous interaction with peers (Durkin, 1995; Jeavons, 1988). Researchers agree that children’s free play opportunities are linked to environmental competence and the development of a sense of self away from adult caretakers (Chawla, 1986; Dovey, 1990; Sobel, 1993). Moreover, outdoor exploration and exercise stimulates an increase in physical activity and reduces the likelihood of childhood obesity (e.g. Holt, Spence, Sehn, & Cutumisu, 2008; Ozdemir & Yilmaz, 2008). Variations in children’s mobility are linked to racial, economic, and gender variables (e.g. Chawla, 2002; Hillman & Adams, 1992; Lynch, 1977; Prezza et al., 2001). For the most part, it is a common claim that children living in urban settings have fewer opportunities for independent mobility, free play, and access to nature (e.g. Camstra, 1997; Kyttä, 1997; Wells & Evans, 2003). However, other scholars found that rural children often exercise urban behaviours and are subjected to mobility restrictions similar to those of their urban counterparts (Matthews, Taylor, Sherwood, Tucker & Limb, 2000; Mattsson 2002; Nairn, Panelli, and McCormack, 2003).

Several key studies on children and the environment have focused on children’s place use (e.g. Barker & Wright, 1951; Hart, 1979; R. C. Moore, 1986). Enlightened by these descriptive works, Heft (1988) developed a functional taxonomy of children’s environments using the concept of affordances, understood as the functional properties of an environment for an individual (Chapter 4). Since that time, there have been numerous empirical studies applying the affordance construct in order to describe children’s place use from a functional point of view (e.g. Chawla & Heft, 2002; Kyttä, 2003; Murtagh & Murphy, 2011). Although affordances that support children’s physical activity are a prime focus among these studies, the notion that children seek opportunities for social interaction and emotion regulation has been suggested by researchers (e.g. Clark & Uzzell, 2006; Kyttä, 2002; Niklasson & Sandberg, 2010). While the needs of children are much the same across different cultures (see Chawla, 2002), children’s place use and behaviours are dependent upon the environmental features and properties of their local environment (Hüttenmoser, 1995; Kyttä, 2002). Murtagh and Murphy (2011) found that children living in segregated Belfast had limited access to safe places. They explained that activity venues and areas were not the most used and valued places, but rather children occupied and preferred places that afforded retreat and restoration. Children’s needs and requirements are heightened by what is and is not available to them in their local environment, and this in turn influences their place use and preferences.

Exploratory studies on children’s favourite locations show that these are prime places with which children develop strong emotional bonds (e.g. Hart, 1979; R. C. Moore, 1986). Chawla (1992) identified childhood preferences within the home, natural settings, social hangouts, and commercial environments. These preferences have been substantiated by other empirical studies on different settings (e.g. Green, 2011; Harden, 2000, for home; Kaplan & Kaplan, 1989, for nature; Woolley & Johns, 2001, for social hangouts; Vanderbeck & Johnson, 2000, for commercial settings). Korpela (2002) recognised that favourite places offer privacy, control, and security, which in turn support the development of self-identity in children. The notion that children’s local place attachments reaffirm their personal identity is supported by other researchers in the field (e.g. Altman & Low, 1992; Twigger-Ross, Bonaiuto, & Breakwell, 2003). Recognising those places that children prefer alongside those that they dislike provides for a more holistic view of children’s environmental experiences (Chawla & Malone, 2003; Woolley, Dunn, Spencer, Short, & Rowley, 1999). Indeed, research has shown that a single place can evoke both positive and negative feelings. This is dependent upon the attitudes and perceptions of individual children, broader socio-cultural surrounds, and seasonal (e.g. weather) influences (Castonguay & Jutras, 2009; Moore & Young, 1978). Van Andel (1990) found that children often viewed natural environmental features as favourable, yet he also recognised that children perceived natural places as boring, scary, and dangerous.

The majority of recent studies on children and the environment have taken place in the western world, among middle- to high-income families (e.g. Carver, Timperio, & Crawford, 2008; Kyttä, 2003; Moore, 2007). Some researchers have attempted ...