- 206 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book is concerned with the application of the behavioural sciences, notably social psychology and sociology, to the study of consumer behaviour. The emphasis throughout is on making these sciences practical for the marketing manager by focusing on those aspects of consumer behaviour which prove useful for managerial decision-making. The introduction defines the scope of the book in these terms and outlines a model for the consumer buying process. The book conlcudes with detailed models of consumer choice.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 Marketing and the Consumer

Modern marketing thought stresses the need of business managers to know who their customers are and why they choose their products rather than those of rival firms. Marketing is not a case of finding or inducing someone to buy whatever the firm happens to manufacture. Nowadays successful management depends more than ever on matching every aspect of the business product, advertising, after-sales service and so on to the satisfaction of consumer needs. This is the essence of consumer-orientation as an integrated approach to business management.

Consumer-orientation stems from the firm's adoption and implementation of the Marketing Concept, a philosophy of business organisation which has three major implications: firstly, the success of any firm depends above all on the consumer and what he or she is willing to accept and pay for; secondly, the firm must be aware of what the market wants well before production commences, and, in the case of highly technological industries, long before production is even planned; and thirdly, consumer wants must be continually monitored and measured so that, through product and market development, the firm keeps ahead of its competitors.

Obviously, this concept of business management is not founded on altruism. It emphasises the profitability of the firm as well as the satisfaction of buyers by showing that profits follow service. The following statement of the marketing concept illustrates these points:

The marketing message is that the consumers are the arbiters of fortune in business, and rightly so; and that by consulting the interest of the consumers systematically both before production is undertaken and throughout the process of distribution, industrial and commercial activity not only brings forth wanted goods and services in a timely and thus economical and profitable manner, but also reveals itself in its proper role, thriving in its service to the community, raising the standard of living and meriting the reward it receives.1

In a competitive economic system, therefore, the survival and growth of firms requires accurate knowledge about consumers: how they buy, why they buy and where they buy as well as just what they buy. Critics of marketing contend that this is unnecessary, that it is possible to manipulate hapless buyers into parting with their money in return for products they do not want. The reality of marketing was stated recently by a director of Unilever, Lord Trenchard,2 in terms which show such criticism to be ill founded:

The concept that technology can decide what the consumer shall have, and the advertiser can condition her to want, is laughable. Every new activity in the food market starts with finding out what consumers want. Many of the largest companies have learnt from experience that if they get it wrong no amount of advertising on earth will compensate. Seventy per cent of new food products fail.

It is not surprising, then, that considerable interest has been expressed in using the behavioural sciences, especially social psychology and sociology, to understand the consumer. As a result, consumers' psychological backgrounds have been investigated in order to establish the extent to which factors like attitudes, motives and personality traits affect buying behaviour; and social influences such as class, status and the family have also been examined for their contribution to our understanding of consumer decision making. The following chapters are concerned with concepts and variables such as these and their usefulness in consumer research. Before this is done, however, it will be valuable to look at recent trends in the application of behavioural science to marketing in order to appreciate the necessity of a critical approach to the study of consumer behaviour.

Behavioural Science

Whatever differences of opinion separate the various types of social scientist, all are agreed on the complexity of their subject matter. None disputes that human behaviour is influenced by a multiplicity of interacting forces and that it presents a very considerable challenge to anyone who attempts to unravel the motivating factors that shape it.

Consumer behaviour contains a particular difficulty in that, superficially at least, it gives the impression that it ought to be relatively easy to understand and explain, even to predict. Basic economics assures us that the quantity of a good demanded is inversely related to price, and even a cursory reflection on the importance of money in industrial societies suggests that economics is right. Of course, economists are quick to point out that there are many real-world deviations from such a rudimentary theory; and familiarity with the actual behaviour of consumers is apt to focus the researcher's attention almost entirely on these deviations rather than on what theory predicts.

Generally, the more consumer researchers have appreciated the complexity of customers' behaviour, the more they have tended to look beyond formal economics for explanations of such activity. Whereas less than twenty years ago a reviewer of household buying behaviour3 emphasised the influence of income as the major determinant of purchase choices, it is usual nowadays for consumer researchers to explain such decision making in terms of a wide range of stimuli and response mechanisms. However, some economists have developed alternative approaches to the study of consumer behaviour such as the 'behavioural economics' associated with George Katona.4 Katona's work concerns the effects of consumers' expectations on aggregate levels of demand, business and consumer motivations to spend, save and invest, and consumer attitudes in times of inflation and deflation.

The application of behavioural science to marketing has not, however, proceeded smoothly. It has tended to be lopsided, confused and uncritical, all of which have tended to reduce its efficacy both in academic or educational terms and in making a practical contribution to marketing. Too much reliance has been placed on psychology and insufficient attention given to other disciplines, particularly sociology but also geography and anthropology.

That psychology, particularly social psychology, has made important contributions to our understanding of consumer behaviour cannot be disputed, of course, and in a recent review, Ramond 5 lists the following concepts and techniques from psychology which have been widely incorporated into marketing studies: perception including absolute threshold; just noticeable difference and perceptual defence; cognitive dissonance; learning including reinforcement; stochastic models; traits (psychographics). The list could be extended, at least to include attitudes and motivation, and although it will be argued in later chapters that some of these concepts have had only a very limited impact on marketing, it is significant that there are so many of them. All that the reviewer came up with from sociology was the single notion of social class, and he comments that 'if social class weren't such an important variable, the tautologies and truisms of sociology would be easier to deride'.

In view of the psychologists' claims that their discipline is the study of behaviour, it is, perhaps, not surprising that so much attention has been given to the psychology of the consumer. Indeed, behavioural scientists in marketing have displayed great zeal in trying to depict consumer behaviour simply as a function of what occurs in the consumer's psyche, his 'black box' or 'central control unit'. Indeed, so great is this emphasis, that there has been little room, even in so called comprehensive models of consumer buying processes, for the influence of social structure on people's choice of goods and services.

Consumer behaviour is a confused field of study because consumer researchers in universities and polytechnics, to whom falls the problem of establishing an integrated discipline, suffer from role ambiguity. Are they primarily academic researchers or should they be pursuing managerial objectives? These need not be mutually exclusive, of course, but there is a tendency to regard them as difficult to reconcile. Neither academic progress nor marketing practice seem to have come off too well from this uncertainty. Marketing academics have often engaged in consultancy and contract work for retailing and industrial firms; but, despite such co-operation, it is not unusual to find areas where there still exists a large amount of mutual suspicion and a feeling that most things academic are of little, if any, practical value.

This also means that much consumer research has been undertaken on an ad hoc basis with little regard for theory or even the integration of new empirical results into the present body of factual knowledge. Several years ago, Philip Kotler 6 wrote that 'the contemporary effort of behavioural scientists in marketing is to analyse well specific aspects of behaviour in the hope that someday someone will put them all together' but there are still few signs that this synthesis is taking place and the situation seems only to have increased in complexity and confusion since then.

A further criticism of the study of consumer behaviour stems from the refusal of some researchers and writers to evaluate the relevance of the concepts, variables and methods which they have 'borrowed' from the parent disciplines. A well-known consumer behaviour textbook 7 opens with an account of several social scientists discussing why a consumer bought a particular car. The imaginary learned assembly consists of an economist, a sociologist, an anthropologist and two psychologists. It is not at all surprising when each of the psychologists offers his own unique explanation of the purchase they have just witnessed, or when the sociologist and the anthropologist cannot decide which aspects of the sale each of them is qualified to explain.

It is usual in texts on consumer behaviour to see each variable or each school of thought within a discipline presented separately and accompanied by an account of the implications of each one for marketing practice. This uncritical approach gives the impression that all the variables or schools of thought are of equal importance both in the study of consumer behaviour and in the parent disciplines themselves. In fact, some approaches are diametrically opposed to others; to accept one is to reject the rest. It is thus misleading to present them side by side as though marketing could simply take what it requires from each school and forget the remainder. The meanings attached to key concepts differ from one school to another and this can only mean confusion if consumer researchers fail to distinguish between them. While it is clearly not the job of the consumer researcher to become involved in the internal disputes of the parent disciplines, once ideas and techniques are transferred to a new context, they must surely be scrutinised for their suitability and validity.

There remains a great deal of controversy in psychology, sociology, anthropology and other behavioural sciences, as well as between these disciplines, about the explanation of human behaviour. Marketing need not become embroiled in this controversy but care must be taken to ensure that explanations of consumer behaviour are consistent and rigorous, and that the behavioural assumptions underlying particular explanations are explicit.

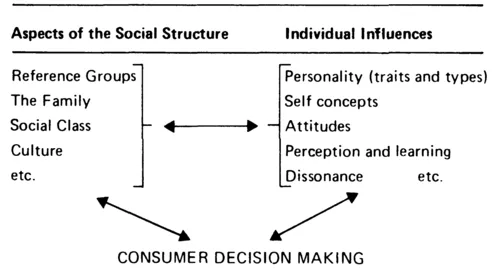

Figure 1.1: Social and Individual Factors in Consumer Choice

This book concentrates on the use of social psychology and sociology to elucidate the behaviour of consumers (see Figure 1.1). Attempts are often made to distinguish these disciplines from one another and this is usually done in terms of their differing levels of analysis or viewpoints since their subject matters are substantially the same. Social psychologists are said to be interested primarily in individuals and their concern with group behaviour is preoccupied with the effects of social behaviour on the individual's attitudes and personality. Sociologists are normally depicted as being interested above all in the structure and functioning of groups and their relationship to social institutions such as the family, education, industry, class and culture. In reality, the differences that once divided behavioural scientists are becoming blurred as social psychologists are increasingly taking aspects of the social structure into consideration while sociologists are becoming more and more interested in the actions of individuals. Some division of labour is still to be found but in jointly executed work it is often difficult to unravel the elements contributed by the social psychologist from those of the sociologist.

In an eclectic and generally empirical discipline like marketing it is therefore unnecessary to make too sharp a distinction between these subjects. Rather, it seems reasonable to assume that consumer behaviour can develop as a single behavioural science. Certainly this is preferable to the development of consumer psychology and consumer sociology as separate and competitive fields, since that would only preserve an artificial dichotomy and ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Title Page1

- Copyright Page1

- Contents

- Tables

- Figures

- Dedication

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Part I Introduction

- Part II Individual Consumer Behaviour

- Part III Group Consumer Behaviour

- A Guide to Further Study

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Consumer Behaviour (RLE Consumer Behaviour) by Gordon Foxall in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.