1.1 A low profile for law

The IPCC’s fifth assessment report, at close to six thousand pages, is an encyclopaedia on the Earth system—its future as much as its past. The work is the culmination of an impressively methodical and coherent response of the natural sciences, along with certain disciplines of the humanities, to the problem of climate change. The IPCC’s report gives prominence to several areas of inquiry. Questions of law and the work of law academics are not among them. Economists and policy specialists are given substantial coverage, by contrast.

In a few places where the report mentions the law as a subject of academic inquiry rather than as a mere instrument of policy, the IPCC’s implication is that legal research has not provided useful answers: ‘Research has not resolved whether or under what circumstances a more binding agreement elicits more effective national policy.’1 An exception to the general attitude might be this statement from the report: ‘Because greater legal bindingness implies greater costs of violation, states may prefer more legally binding agreements to embody less ambitious commitments, and may be willing to accept more ambitious commitments when they are less legally binding.’2 However, the statement seems a priori: a deduction from common sense rather than a true discovery. It too carries a negative connotation about the law in its suggestion that a commitment with legal force could retard ambitious action against climate change.

If the IPCC’s reports were taken as the measure of relevant enquiry on climate change, we would have to concede that law academics have yet to secure a disciplinary space for themselves or have their insights recognized outside their own field. Alternatively, their contributions or failings are being attributed to international relations, economics, or policy analysis—a classification that in many cases is deserved because the legal content of articles on climate change issues published in law journals is often minimal. Law—that ‘system of rules that a particular country or community recognizes as regulating the actions of its members and may enforce by the imposition of penalties’3—seems to have played a subservient role in the overall response to climate change, even as many legal scholars have engaged professionally and at length with the climate change field.

Niggling concerns about the role of academic law in the conversation on climate change invite us to consider the extent of the substantive climate change law presently in place and its contribution to the conduct of states in the international community. In Mayer’s words, the search is for a ‘climate law in a narrow sense—a set of norms forming a special legal regime, having its own object and purposes and its own doctrine’.4 It is also an inquiry into the possibility that climate law is much less than what some legal academics have assumed,5 both in substance and as a guide to states. It could explain the law’s poor showing in the IPCC reports.

Questions about the existence of climate law and the compliance of states with the requirements of the climate change regime are linked, as suggested by this book’s title. The IPCC’s reports may be silent on the law, but they are vocal about the fact that state action against climate change is insufficient and even reckless. The two conditions could be related. An absence of climate law would be relevant to an explanation of state conduct found to be unambitious or incoherent, just as an acknowledged and binding law would be relevant to an explanation of state conduct found to comply with the regime’s objectives. For explanatory reasons it is important to know whether the state conduct criticized by the IPCC occurs in a context of laws or in a context not defined by clear legal obligation.6

Law is often merely facilitative. But it can also be a force in its own right. Where it has such force, it is said to have a normative quality (normativity). Beyerlin calls it ‘the capacity to directly or indirectly steer the behaviour of its addressees’, and Porter calls it a law that has ‘purchase on a community’.7 Norms are ‘prescriptions for action in situations of choice, carrying a sense of obligation, a sense that they ought to be followed’.8 Law of this kind arises from principles of justice, morality, or other first principles.9 It has been called a ‘legally binding norm’ or a ‘fixed norm’.10 Applied to the international sphere, normative law is capable of constraining and shaping the behaviour of states. It has ‘causal significance’ in relation to state behaviour.11 Normative law is different from ‘facilitative law’ (the implementation arm of policy) which is instrumentalist and subordinate to politics, and different again from soft law, which guides but does not compel.

One could illustrate the special quality of normative law by drawing from the arena of human rights law. There, solidifying legal norms in the second half of the twentieth century compelled legislatures to pass laws to regulate both state and individual conduct and penalize the abuse of ‘human rights’, for reasons not only of government policy but of (newly recognized) legal imperative. Once enacted, the protection of human rights became an institution to be reckoned with, and because it was backed by independent norms it ran a low risk of repeal. Similarly, large tracts of pollution law could not, nowadays, conceivably be repealed. They attach to ingrained norms. At the other end are technical laws that merely implement policy and have no value outside of their instrumentalist, facilitative, function.12

Where a legal ‘system of rules’ develops in an area of conduct that is seen as important to national well-being, a legal specialization tends to form around it. Human rights lawyers, practising and academic, work with such a system of rules. Human rights law is underpinned by a system of justice, of right versus wrong. The comparison with human rights law makes climate change law look abject. While it has gained some ground since the 1990s, it has yet to give rise to a systemof rules. The few rules that it can lay claim to are fragmented and weak. There is some potential for this to change, although the day when climate law becomes a regular legal specialization seems far off.

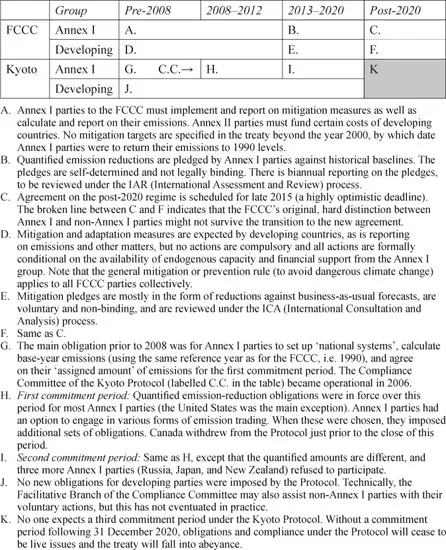

Table 1.1 Summary of treaty obligations under the international climate change regime. The letters in the table are explained immediately below it.

1.2 International climate law

The structure of obligations under the international climate change regime is shown in Table 1.1. Two treaties, the FCCC and the Kyoto Protocol, each with different obligations for developed and developing countries, have expanded their operations and enriched their terminology over time, through decisions of the state parties and the (much rarer) adoption of amendments. The most salient transition years were 2008 for the Kyoto Protocol and 2013 and 2020 for both treaties. Of the two treaty regimes, the obligations under the FCCC have changed the most, and are expected to continue to change. The FCCC is a much more general and accommodating regime than the Kyoto Protocol.

The normative law that has emerged from the two treaties is discussed in detail in Chapters 2 to 5.

From its very beginning, the international climate change regime did not seek to reverse global warming. It accepted that some warming was inevitable. According to the FCCC, states are to limit their emissions to avoid ‘dangerous’ warming.13 With time, the IPCC offered a quantification of the upper limit: ‘a 2°C increase [is] an upper limit beyond which the risks of grave damage to ecosystems, and of non-linear responses, are expected to increase rapidly’.14 That limit was adopted by the FCCC: ‘deep cuts in global greenhouse gas emissions are required according to science … so as to hold the increase in global average temperature below 2°C above pre-industrial levels’. FCCC parties are required to ‘take urgent action to meet this long-term goal … on the basis of equity’.15

The imperative expressed in the last two sentences may be considered the foundation of international climate law. It specifies the action required of states (deep cuts in emissions), a method by which to calculate the necessary and sufficient action by states (avoidance of 2°C warming), and a response time line (urgent action, which suggests immediate action). It does not specify how the action is to be shared among states, beyond the requirement that it must be done equitably. The normative content of the law could hardly be more potent: its breach could lead to ‘grave damage to ecosystems’. Ecosystems support human welfare, so acting to save them is a matter of necessity, perhaps moral necessity, not choice.

Climate law thus has a moral, existential foundation which rivals that of any other area of the law. What it lacks is elaboration in the direction of greater specification. Until states can agree on how to implement the general law, and through that agreement create new, concrete obligations, cuts in emissions will be gestures of good will and always fall below what the general law requires.

The FCCC’s foundational rule helps us to distinguish between rules of law that are closely or remotely related to it. That is, it gives us a workable definition of climate law that is not so broad as to tempt us to assemble a kind of ‘horse law’. An obligation upon a state to limit greenhouse gas emissions in its territory to a specified amount below (or, where justified by its circumstances, above) a historical reference year may be called a ‘core-outcome obligation’ because it directly addresses the objective of the FCCC to reduce anthropogenic emissions to safe levels. Even if the obligation is such that it applies only to a minority of states that cannot by their own combined effort reduce global emissions to safe levels because of their low proportional contribution, it is still close to the core of the international climate change law because its effect is to limit emissions, even if not by a globally meaningful amount. This kindof rule has also been called a primary rule16 or a core treaty goal.17

The FCCC itself contains one, and only one, core-outcome rule, now expired. I discuss it in Chapter 4, where I refer to it as the specific mitigation rule (to be contrasted with the general mitigation rule discussed above). The climate change regime’s most famous core-outcome rule is the Kyoto Protocol’s capping of the emissions of (most) Annex I parties over two commitment periods (2008–2020). The rule has this form: ‘The country shall limit its emissions to a fixed amount above or below a designated reference year.’ In the first commitment period, the rule obliged Annex I parties to keep their averaged annual emissions for 2008–2012 within a certain percentage of their 1990 emissions. The rule is directly connected to the FCCC’s foundational law as it operates to mitigate the causes of climate change in several developed countries. According to the definition I have presented, it is climate law. However, the Protocol rule does not reduce global emissions to safe levels. It is a step removed from the innermost core of climate law. The difference is significant, because the normative hold of the FCCC’s foundational law derives entirely from its objective to prevent a dangerous alteration of the Earth system.

The Protocol rule is a creature of treaty law, cut down by qualifications. By 2014 the rule had occupied the climate-law pedestal for about seven years but was not generally held in high regard. The number of Annex I parties rejecting the treaty had risen to five.18 Only a handful of countries had formally accepted the Doha Amendment to the Kyoto Protocol which put in place the mechanisms for the second commitment period. It is just possible that the amendment will never formally enter into force.19

Heartfelt support for the Protocol’s core-outcome rule among Annex I parties was always much less than the number of ratifications of the Protocol might suggest. Well before countries began to drop out in 2011, Annex I parties were pressing for the rule (compulsory mitigation) to be extended to developing countries. That demand, which was gathering force already in 2009, elicited fierce resistance from developing countries, which claimed that the responsibility for mitigation applied to the Annex I group alone. Under those conditions, the Protocol’s rule could not lead to the further development of the FCCC’s foundational law.

In 2010, Brunnée and Toope wrote about the international climate change regime thus:

As far as specific substantive commitments are concerned, shared understandings do not currently extend much beyond the proposition that the existing regime be developed to include deeper commitments for more parties, with industrialized countries taking the lead. [R]obust agreement on interim targets for industrialized countries and long-term targets for major developing countries remains elusive.20

Nothing had changed by 2014 to diminish the accuracy of this comment. The ‘pledge’ period of mi...