![]()

1. Learning to Be Transnational

Japanese Language Education for Bolivia’s Okinawan Diaspora

Taku Suzuki

VARIOUS DEFINITIONS OF “HERITAGE LANGUAGE” and heritage language education notwithstanding, within the context of the United States and Canada, where the concepts were developed, heritage languages are typically defined as “the languages of immigrant, refugee, and indigenous groups… other than English.”1 Heritage language, encompassing both immigrant and indigenous languages, is the language “spoken in a community where that language is being replaced by a language of wider communication.”2 Heritage language education, its advocates argue, helps children and youth in non-majority-language–speaking minority groups within a state “feel connected to their roots, or…to participate more fully in the life of their [heritage linguistic and heritage cultural] community and contribute to the preservation of its beliefs and practices.”3 The concept of heritage language has gained acceptance among linguists and educators in Europe and Australia. In these regions, in which linguistic diversity is increasing due to the influx of new immigrant groups, the preservation and/or revitalization of distinct regional and indigenous languages that differ from the official national language has long been a crucial issue. (Examples include Corsican in France, Sámi in Norway, and aboriginal languages in Australia.)4

In these studies of heritage language and heritage language education, linguists typically understand heritage language education to be a defensive strategy that immigrant minority groups adopt in order to retain the “culture” and tradition of their ancestral homeland against the overwhelming pressure of linguistic, cultural, and identity assimilation in their host society. Heritage language education, it is expected, thus facilitates the formation of a strong sense of solidarity among these vulnerable communities; hence, the terms “community language” and “minoritized/minority language” are often used interchangeably for heritage language.5 Along with other contributors in this volume, I challenge the underlying assumptions of heritage language scholars and practitioners that have shaped the definitions and significances of heritage language education.

Specifically, this article calls into question two popular assumptions regarding heritage language and heritage language education: First, that immigrant and refugee groups consider heritage language as an official language in the nation-state from which they emigrated. This belief collapses the “heritage” of heritage language into national heritage. Second, heritage language is a vulnerable language on the verge of getting swept away by the national language of the nation-state of their current residence. Joining the recent critiques of the North American– and English language–centered conceptualizations of heritage language and heritage language education,6 this article challenges these assumptions in two ways. First, I contend that, while immigrant minority groups commonly choose the national language of their ancestral nation-state as their heritage language, this choice is far from an inevitable or “natural” one for the members of immigrant groups who were marginalized in the nation-states of their migratory/ancestral origin. The designation of heritage language for the immigrant groups and their native-born offspring could involve a transformation in their conceptualization of ancestral homeland from a sub-national territory to a national one. Heritage language education, in other words, involves a process of “nationalization” of the immigrant group’s ancestral homeland, which takes place in the nation-state of their current residence. Second, I argue that heritage language education is not always a defensive strategy for immigrants and their offspring in the face of the host society’s assimilating forces, since in certain circumstances heritage language can function as an effective means to symbolically express their power vis-à-vis the majority of the nation-state of their residence. In a host nation-state where possessing (real or imagined) transnational connections outside of its state borders is highly valued, teaching and learning the language of their ancestral origin constitutes a process of making and maintaining the boundary between the majority of the host nation-state and themselves by not only actively embodying and displaying their difference as being of foreign origin, but also by their economic and symbolic power implied by their (real or imagined) transnational connections to the nation-state of their origin.7

Drawing upon my field research on Japanese language education in an Okinawan immigrant settlement in rural Bolivia, this article explores the locally specific considerations behind the immigrants’ heritage language education, in which the standardized Japanese language, the “national” heritage language of Okinawans, rather than the Okinawan language, or Uchināguchi,8 which the majority of the immigrant generation had spoken most comfortably before and after the immigration to Bolivia, became their group’s heritage language in Bolivia. Moreover, for affluent large-scale farm owners in rural Bolivia, who employ working-class Bolivians with no Japanese or Okinawan ancestry (“non-Nikkei Bolivians,” hereafter) as farm laborers, their acts of learning and using standardized Japanese constitute what sociologist Pei-Chia Lan calls “boundary work,” everyday practices that “weave institutional divisions and cognitive classification” between groups.9 Their linguistic practices in Colonia Okinawa, whether within educational settings or in the community at large, were, consciously or not, an engagement in boundary work, a way they aligned themselves with or distinguished themselves from other groups.

My field research in Colonia Okinawa lasted from 1997 to 2001, but the bulk of information used in this essay comes from the eleven-month-long research I conducted from 2000 to 2001. During the course of my research, I was a volunteer teacher of Japanese language in two Colonia Okinawa schools, which nearly all Okinawan-Bolivian students attended. As a Japanese national, who was born and raised near Tokyo in mainland Japan and had lived much of his adult life in the United States, I was asked by the community leaders to teach third-grade and fourth-grade Japanese classes, and, during the winter break, to conduct English lessons for middle school students. As a school staff member, I not only observed the daily activities of the students in and outside of the classroom, but I was also actively involved in extracurricular activities both within and outside the school. I lived with three different Okinawan-Bolivian families during my research. During my stays with these families, I observed how Okinawan-Bolivian family members communicated with their non-Nikkei Bolivian employees (farm laborers or domestic workers), as well as among themselves.

I begin by outlining the history of Okinawans’ tenuous relationship with the Japanese nation-state, and contextualizing Okinawan immigration to Bolivia and the foundation of Colonia Okinawa within this relationship. I then describe Japanese language education in Colonia Okinawa, its foundation and transformations. The process has been shaped as much by the immigrant community’s desire for maintaining “national” cultural heritage as by its need to mark the ethnic/class boundary between themselves and their local Others. Finally, by providing a few ethnographic “snapshots” of Okinawan-Bolivians’ language use in Colonia Okinawa, I will illuminate the linguistic boundary work in which Okinawan-Bolivians engage in their lives.

Modern Okinawan Diaspora and Colonia Okinawa

Emigration from Okinawa in modern times began in 1899, when Tōyama Kyūzō, a democratic rights activist, led a group of Okinawans to Hawai’i to work on sugarcane plantations.10 While the dispersal of Okinawans overseas in the twentieth century proceeded, as Robert Arakaki argues, in the form of an “apolitical labor diaspora,” the Okinawan diaspora’s history and subjectivity are profoundly political, shaped by Okinawans’ struggles under Imperial Japan and, later, under U.S. military occupation.11

Despite numerous political and military intrusions by China and Japan since the seventeenth century, and even after becoming a tributary state to both China and Japan in the seventeenth century, the Ryūkyū Kingdom flourished as an international trade hub in East Asia and Okinawans enjoyed economic and cultural prosperity. Under Ryūkyū Kingdom rule, Okinawans developed a distinct culture and language by creatively blending cultural and linguistic elements from Southeast China, Korea, and Indochina.12 It is commonly believed that the Japanese and Okinawan languages sprang from a common parent language, although Japanese absorbed far more Chinese into its older language forms than did the Okinawan language. As a result of a long process of cultural and linguistic mixture, the Okinawan language, while philologically similar, remained distinctively different from the standardized mainland Japanese language. After the Meiji government’s annexation of Okinawa in 1879, known as the Ryūkyū Shobun (Ryūkyū Disposition), the kingdom became a prefecture of Japan and Okinawa became the Japanese empire’s laboratory for colonial policies in culture and economy. The Meiji government rigorously instituted linguistic and cultural “Japanization” through school education in order to “produce” Japanese national subjects, an agenda that was later applied to the peoples of Taiwan, Micronesia, and the Korean peninsula.13 After the annexation, enormous economic obligations to the central government were imposed on Okinawans in the form of newly instituted land tax laws, and Okinawa’s economy became unstable as Tokyo promoted sugar production as the prefecture’s sole economic backbone. To rescue the nearly bankrupt Okinawan economy and to cope with the increasing population pressure, the prefectural and national governments promoted overseas emigration. Emigration had two effects: it reduced the population and it generated income through remittances from émigrés.14 By 1927, an estimated 15 percent of the prefecture’s population lived outside of Okinawa: more than 32,000 Okinawans were working in industrial areas in Japan proper and another 26,500 had migrated to foreign countries.15 In the 1920s, as the U.S. government gradually curtailed, and later prohibited, Japanese immigration, more Okinawans were encouraged by the Japanese government to migrate to the Philippines, Micronesia, Taiwan, and, from the late 1930s to 1940s, Manchuria (northeast province of China). Between 1899 and 1941, the number of emigrants from Okinawa Prefecture totaled 72,789, or 11 percent of all emigrants from Japan, second only to Hiroshima Prefecture.16

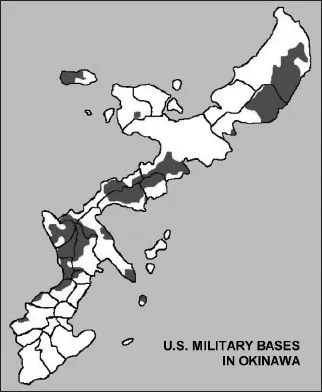

“The Prefecture of Okinawa remains home to 75 percent of U.S. bases and the majority of U.S. military forces in Japan. (The bases occupy 20 percent of the Okinawa Hontō Island.)” (Credit: Wikimedia Commons)

Okinawans in Okinawa and Okinawan émigrés abroad both lived in a precarious subject position vis-à-vis the Japanese nation-state and Japanese mainlanders, or Naichi-jin.17 Historian Eiji Oguma argues that Imperial Japan sought to absorb Okinawans into the Japanese nation-state as “children” of the “multiethnic Japanese family,” which was imagined as a mixture of heterogeneous Asian peoples.18 Imperial Japan promoted itself as a harmonious and benevolent “family state,” or kazoku kokka, that embraced diverse ethnic groups within the empire, uniting them as a family with a common ancestry. Within Imperial Japan’s multiethnic family state ideology, colonial expansion was justified not only as repatriation of the “original” Japanese peoples, but also as the paternalistic adoption of other Asians, who were perceived as wrongly raised, and therefore underdeveloped, “children” of the Japanese nation.19 As adopted “children,” colonized subjects, including Okinawans, were expected not only to abandon their previous customs, beliefs, and language in order to become indistinguishable members of the Japanese nation, but also to “naturally” obey the household head, the Japanese government, and the elder sibling, the majority Naichi-jin population.20 Under this logic, Okinawans, as young “children” of the family state, did not deserve the equal rights as the Naichi-jin; although the Meiji government enforced educational policies to facilitate Okinawans’ cultural and linguistic assimilation, it took decades of advocacy campaigns by Okinawan intellectuals before Okinawans were given the same legal rights as Naichi-jin’s.21

Their ambiguous subject-position within the Japanese “family state” left Okinawans with a psychological trauma when they faced Japanese Naichi-jin in Japan or in overseas migratory locales.22 Naichi-jin émigrés frowned upon Okinawans overseas as “the other Japanese,” who were “almost, but not quite” the same as Naichi-jin, and frequently discriminated against them.23 In response, Okinawan émigrés in Brazil, Peru, and Micronesia, who daily faced prejudice from the Naichi-jin migrants, tried to evade humiliation and discrimination by self-inspection and self-acculturation. Okinawan immigrant community leaders in Micronesia, for instance, organized a Lifestyle Reform Movement (seikatsu kaizen undō) that prohibited community members from using their native language and practicing their traditional customs, and sometimes, in an effort to highlight their identity as “Japanese” nationals, blatantly discriminated against locals in their migratory destinations.24

The struggle of Okinawans and the Okinawan diaspora continued even after the end of the tragic Battle of Okinawa in 1945, which resulted in the deaths of more than one-fourth of the entire local population of the Okinawa Hontō Island, the largest and most populous island within Okinawa Prefecture.25 Japa...