![]()

1 Introduction

Susanne Oxenstierna and Veli-Pekka Tynkkynen

Russian energy policy attracts a great deal of attention at home and abroad because it affects so many different policy fields and interests. Energy is and will remain the core business of the Russian economy and it is the only good in which Russia has a comparative advantage and can compete for increasing wealth through international trade. Being a large energy player worldwide and the largest energy supplier to Europe, energy is also a vital part of Russia’s foreign policy and security policy, which is reflected in the literature (see e.g. Perovic et al. 2009). Furthermore, energy exports pay a large part of the public expenditures in the federal budget and this has given energy a paramount role in Russia’s domestic policies and in the regional development of its vast space. The Russian government is deeply involved in the energy sector and it has increased state ownership and control since the early 2000s, which has led to an increasing politicization of the energy assets and trade. The securitization of energy, implying that energy is not just a question of generating electricity and earning export income, but also a question of national security for Russia as well as for its trade partners, has occurred since the end of the 1990s when oil prices started to rise and Russia began changing the terms of trade for former socialist countries linked to its energy grid. Energy relations create inter-dependencies between companies, countries and political actors and even with a sound commercial basis for the initial interdependence, energy may become a political issue and be used as an ‘energy weapon’ in disputes between the parties.

The debate on Russian energy has been dominated by issues related to Russia’s hydrocarbon production and export. The reasons are quite obvious: with surging oil prices in the 2000s Russia got out of its transition decline and became a high-growth economy able to service its international debt, regain global influence and increase the population’s standard of living. As European countries have become increasingly dependent on Russian energy, concern has been voiced regarding the security of supply of Russian oil and particularly gas, both in terms of physical availability and of political trust. Gas deliveries were cut off for economic and political reasons on several occasions in the 2000s. The disputes with Ukraine in 2006 and 2009 affected large parts of Europe, and raised serious concerns about whether Russia is a secure energy supplier.

For its part, Russia has raised concerns regarding the security of demand. After the gas incidents in the 2000s, Europe diversifies its energy suppliers. In addition, the EU climate and energy package enacted in 2009 aims to ensure that the European Union (EU) meets its climate and energy targets for 2020. These targets are known as the ‘20–20–20’ objectives and include a 20 per cent reduction in EU greenhouse-gas emissions from 1990 levels, raising the share of EU energy consumption produced from renewable resources to 20 per cent, and 20 per cent improvement in the EU’s energy efficiency. The 20–20–20 objectives enhance reduction of energy consumption and an increasing share of renewable energy sources in the EU’s energy mix, which decreases the demand for Russian gas. Added to this comes the shale gas revolution and dumping of LNG on European gas markets. To compensate for this, Russia has turned East and attempted to develop its energy relations with China and other Asian countries. This is linked to new types of challenges for Russia. In addition to a pronounced level of suspicion and uncertainty prevailing in Russia-China relations, China’s rich unconventional gas resources cast further doubts on Russia’s central role as an energy supplier for this region. A new more recent challenge is the antitrust case launched by the European Commission’s Directorate-General for Competition against Gazprom on 4 September 2012 (Riley 2012). This case has the potential of radically diminishing Russia’s dominant role on European gas markets, but is also an opportunity for initiating a long-needed reform of Gazprom and Russia’s domestic markets.

The crucial importance of the energy sector and energy export for Russia and the significance of secure energy supply to Russia’s customers implies that ‘security’ is a key aspect of Russian energy policies. In the literature, security is used as a main variable in analysing interaction in energy policy between Russia and its main clients. The fact that Russia uses its position as a regional energy power to affect countries dependent on its oil and especially gas has been shown by Larsson (2008; 2010) and Smith Stegen (2011). Particularly in the CIS countries Russia has used the ‘energy weapon’ to attain certain privileges (Balmaceda 2011; 2012). As noted by Wenger (2009: 241), the energy system is a key link between global markets and local conflicts in a globalized world. For these reasons, growing interdependencies in the energy area require better coordination between countries as regards energy and foreign and security policies.

Objectives and methodology of the study

The first objective of the book is to provide a picture of long-term trends in Russian energy policies, identifying challenges and analysing the prospects of these being addressed and solved by the proposed policies during the coming twenty years. The second objective is to highlight selected interdependencies of Russia’s foreign energy relations and to discuss their implications for Russia and its trade partners now and in the future. Besides these objectives, several contributions in the book investigate aspects of the crucial interactions between the energy sector and domestic policies and their implication for the economic and regional development in Russia.

Russian energy is a multidisciplinary topic and many social scientists follow Russian energy development from different positions. One motivation behind this book comes from the difficulty in covering this multifaceted topic and its many multifarious aspects with just one disciplinary approach. The volume consists of twelve chapters with contributions from fourteen authors of different academic backgrounds from nine countries, which have resulted in a rich variety of issues discussed and methods used. The authors have chosen their particular research issues themselves. All authors are social scientists, which means that there is some common ground for the research. However, because economists, political scientists and geographers differ in disciplinary specific methodology and focus on different issues there is no explicit common methodological foundation for the book. Each author has stated his or her approach in their respective chapters. Nevertheless, ex post with all the chapters at hand, we may define some main approaches and themes that characterize the research presented in this volume.

One approach is to start off with the official Russian documents that describe what the Russians say they intend to do and compare these stated policies and intentions to other strategies and forecasts of the Russian energy sector and discuss their realism and implications. A variation is to assess the official strategies with reality. This approach is used widely e.g. in Chapter 2 which presents and analyses the implications of the current Russian Energy Strategy up to 2030 (ES-2030, Ministry of Energy RF 2009); also in Chapter 8 which discusses the power sector against the background of the general power strategy (Genskhema); in Chapter 9 which compares the ES-2030’s forecasts regarding the use of nuclear power in power generation with IEA forecasts; and in Chapter 12 which compares a wide range of scenarios relative to the development of the Russian energy sector and foreign policy. The comparisons of official strategies with other forecasts or implementation are mainly geared at the economic implications of Russia’s energy policies and an assessment as to their realism. Another approach is to focus on the interdependencies between Russia and its energy trade partners, particularly in the gas trade, a topic which is deeply linked to national security. This approach is applied in Chapters 3, 4 and 5 where both economic and political aspects of the problems are highlighted. In Chapter 7, a Baltic view is taken on Russia’s foreign energy policy, which provides a specific perspective into the interpretation of these interrelations. A third approach looks at the close links between Russia’s energy policy and domestic policy and foreign policy, respectively. Chapter 6 which investigates the possible politicization of trade in renewables, Chapter 10 with its analysis of the role of private oil companies and Chapter 11 with a focus on regional development of Pacific Russia are good examples of this. Obviously, many chapters use combinations of these three starting points in their analyses. The book offers the reader examples of a broad range of methods from advanced formal analysis to an ambitious study of Russian original sources.

The context

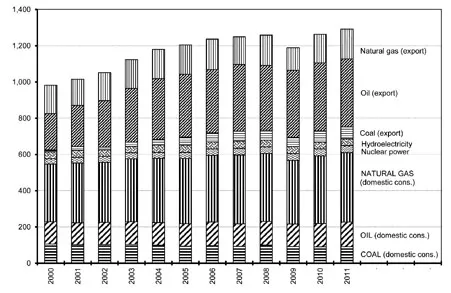

During the 2000s, Russian energy production rose dramatically as a result of increased foreign demand for fossil fuels (oil, gas and coal). As Figure 1.1 shows, Russia exported about one-third of its energy production in 2000 and as much as almost half of the total by 2011. Crucial to the country’s ability to meet rising demands was the high price of oil throughout the period. This enabled it to step up its exploitation of existing deposits and vigorously expand both its oil and gas pipeline system and other export routes.

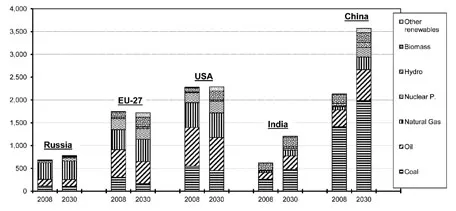

Domestic energy consumption also increased in the 2000s, but only by 11 per cent for the period as a whole. It is still below the 1990 level, and, according to some OECD/IEA scenarios, it will remain so at least up to 2020 (Oxenstierna and Hedenskog 2012: 312). In the IEA’s main 2010 scenario (the ‘New Policies Scenario’, NPS), in which countries implement environmental and energy-saving measures they have already committed themselves to, the level of domestic demand in Russia increases marginally (Figure 1.2). Energy use in the EU, on the other hand, is expected to decline. This contrasts sharply with the situation in the other emerging economies, especially in China. China overtook the US as the world’s largest energy user in 2009, and it is estimated that it will see a dramatic increase in energy consumption during the period (ibid.). Russia stands out in that it will continue to use gas as its main source of energy, in contrast to the other countries, where coal and oil are the principal sources.

Figure 1.1 Russia’s energy production by fuel divided into domestic consumption and export 2000–11; mtoe

Source: FOI based on BP (2012).

Figure 1.2 Domestic consumption and energy mix 2008 and 2030 in selected countries, according to the IEA’s New Policies Scenario*; mtoe

Source: FOI based on IEA (2010).

Note: *The New Policies Scenario (NPS) assumes the introduction of a number of measures to combat the carbon dioxide problem.

In power generation, Russia uses mostly gas but also coal, hydroelectric and nuclear power. The ES-2030 foresees a decline in gas and an increase in the use of other sources for power generation, since gas will be needed to meet international demands.

Russia remains one of the most energy-intensive countries in the world. In 2005, energy intensity per unit of GDP was 0.42 kg of oil equivalent, which is twice as high as that of the two largest energy users, the US (0.19) and China (0.20). Assessment have indicated that Russia should be capable of reducing its energy consumption by 45 per cent (Oxenstierna and Hedenskog 2012: 128). President Dmitry Medvedev signed a decree in June 2008 laying down that energy intensity in the Russian economy was to be reduced by 40 per cent by 2020. A law was subsequently passed and the government also adopted an action plan for the promotion of energy efficiency. At the same time, a new Russian energy authority (Rossiiskoye agentstvo energetiki) was tasked with implementing the planned improvements in energy use (World Bank 2010). Energy savings is a catalyst that Russia has not previously made use of in its energy policies and improved energy efficiency could be of key importance in the 2010s. It is also clear that technological renewal of the energy sector could act as an engine of modernization of the Russian economy. As pointed out by Mau (2010), modernization of the energy sector and further emphasis on energy exports are both essential if Russia is to progress to a more modern, innovative economy. Thus, contrary to what is sometimes claimed, priority to the energy sector does not necessarily conflict with the modernization efforts as long as investment and technological renewal proceed competitively and give innovative new enterprises the chance to grow.

Europe is Russia’s most important external energy market and Russian hydrocarbons are crucial for the European Union to meet its energy needs. In 2011 almost 90 per cent of oil, 70 per cent of gas and 50 per cent of coal exported from Russia went to the EU (Ministry of Energy RF 2011). At the same time, imports from Russia represented over one-third of the EU’s gas, one-third of the EU’s crude oil imports and 30 per cent of its coal imports. It follows that revenues from gas and oil exports are of great importance to Russia, and the EU views energy as a key component of security and still depends on Russia as a supplier of energy. One central question is why it has proved so difficult to develop trust and long-term agreements between these two interdependent partners. Russia argues that its activities in the energy field are motivated by economic goals, but they may also be interpreted as a strategy for strengthening the regional superpower status of Russia and to use energy for coercing other countries to behave in Russia’s interests. Among the EU states there have been difficulties in reaching a common platform in the policy regarding Russian energy due to different degrees of dependencies of Russia and different economic and historical conditions. Dependence on Russian energy varies considerably within the EU. Some EU countries have been strongly opposed to a common European energy policy. As a rule, these countries have access to alternative fuels and the delivery of gas from other countries besides Russia, and have robust energy companies able to offer Gazprom access to financing, technology and major markets. The countries of Central and Eastern Europe have had fewer alternatives and are usually dependent on Russian oil or gas for their energy supply (70–100 per cent) (Oxenstierna and Hedenskog 2012: 137). These countries have tended to be more keen on a common European energy policy towards Russia.

Together with alternative gas supplies entering Europe, such as LNG and shale gas, the European Commission case against Gazprom is a serious attempt at enforcing competition rules to create a liberalized European gas market and might substantially change the conditions for Russian gas in the EU. As pointed out by Riley (2012: 13), this is an opportunity to induce much needed reforms in Gazprom and the broader Russian gas market. However, resilient resistance to the antitrust process may be expected. Increasing exports to Asia is an option that Russia explores in its attempt to ensure security of demand for the coming decades. China’s energy usage is growing (Figure 1.2), but China is a different trade partner from Europe and acts independently and states its own terms. Apart from joint projects with Russia, China has invested heavily in Central Asian energy resources and infrastructure, including oil and gas pipelines from Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan. In addition, China’s shale gas resources are assessed to be significant, further complicating energy relations between China and Russia.

Organization of the book

The organization of the chapters in this book was not premeditated and each chapter stands for itself. For the reader, who might want to read the book from cover to cover, the logic behind the order that we finally chose is that it starts with a chapter that presents and analyses the current Russian energy strategy up to 2030 (ES-2030), which gives an overview of the long-term tendencies in Russian energy policies...