![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction: Sexual Panic States

The phobic avoidance of sex and sexual aversion disorders are the primary complaints of many patients who seek help for their sexual difficulties (Crenshaw, 1985). But despite their high prevalence, sexual panic states have received surprisingly little professional attention, and students in the field are hard put to find literature on this topic. Thus, sexual phobias have been specifically excluded from the category of phobic disorders in DSM-III (1980) and these syndromes have received no mention at all in the section on psychosexual disorders.

Recently, however, there has been growing interest in sexual panic states, and the American Psychiatric Association committee on psychosexual dysfunctions has recommended the addition of the new diagnostic entity Sexual Aversion Disorders which is to be subsumed under the larger category of Disorders of Sexual Desire in DSM-III-R. In our experience this is a valid clinical entity which merits the attention of sex therapists, and this book is devoted to these long neglected syndromes.

The second objective of this volume is to consider the implications of the high coincidence of panic disorder and sexual phobias and aversions which we have observed in our patients. These dual syndromes have provided an excellent vantage for studying the fascinating interplay between a presumably biological vulnerability to panic and the impact of cultural, neurotic and relationship stressors. In addition, we found that our sexually phobic patients with underlying panic disorders were often too anxious and panicky to benefit from sex therapy. For this reason we have been using medication known to block panics with these patients, and our experience with the combined use of antipanic drugs and psychodynamically oriented sexual therapy gave us the opportunity to integrate biological and psychodynamic concepts of sexual anxiety and to develop comprehensive treatment strategies which are also described in this book.

Panic Disorder

Panic Disorder is a relatively new diagnostic category which comprises a group of anxious phobic patients with panic attacks who are not amenable to psychological treatments or to major or minor tranquilizers, but who have an excellent response to tricyclic antidepressant drugs.

Donald Klein, who first described this syndrome, has postulated that the anxiety experienced by patients with panic disorder is qualitatively different from that of neurotic individuals, and involves a pathologically sensitive CNS anxiety-regulating mechanism. According to this theory, this biological abnormality predisposes these individuals to spontaneous panic attacks, phobias, excessive separation anxiety, and the development of detrimental avoidance behaviors (Klein, 1964, Klein, 1980). Klein’s finding that tricyclic antidepressant drugs (TCA) block the panic attacks of patients with panic disorders has been confirmed by numerous investigators, and other types of antidepressants, including drugs in the monoamine inhibiting (MAOI) category, have been found to have similar antipanic effects. This discovery constitutes a major breakthrough which has considerably improved the prognosis for patients with panic disorders, and these medications are now considered the treatment of choice for this syndrome.

The first time I recognized a patient with both panic disorder and sexual dysfunction was in 1976 at the human sexuality program of the Payne Whitney Clinic of the New York Hospital-Cornell Medical Center.1

Case Vignette #1: Rosa and Richard

Rosa was a 25-year-old woman who had been married to her 27-year-old husband for four years. The couple had known each other since high school and their relationship, apart from their sexual difficulty, was loving and close. The patient had no desire for sex and avoided all physical contact with her husband; in recent years she had developed an intense aversion to any physical intimacy with him. It was of special interest that this patient had failed to improve both with individual psychodynamically oriented psychotherapy and also with behaviorally oriented sex therapy. Rosa reported that two years of twice weekly psychotherapy had been beneficial in improving her depressed mood, but did not relieve her sexual difficulties, while the behaviorally oriented sex therapy program, which she and her husband had attended once a week for four months, actually aggravated her sexual fears and avoidance.

The patient’s stated complaint was an absence of sexual desire (ISD) and sexual aversion, but the evaluation revealed that her low level of sexual interest was secondary to a phobic avoidance of sex. Her complaint was specific to sex with a partner and she was capable of having orgasms when masturbating by herself and immersed in sexual fantasy. However, Rosa had never been able to experience erotic sensations or arousal with her husband, who had been her only sexual partner. On several occasions, she had panicked when he had tried to make love to her and she had developed profound anticipatory anxiety and avoidance as well as, in the last four years, an increasing aversion to any situation that even remotely suggested sex.

In addition to her long-standing sexual complaint, this patient met the diagnostic criteria for panic disorder. She reported having experienced spontaneous panic attacks during her youth. She had also suffered from several transient phobias, had difficulties with separation, and had failed to respond to psychological therapies. Rosa’s underlying panic disorder had never been diagnosed, nor had she been treated with appropriate medication in any of her prior therapeutic experiences.

This patient responded to a course of psychodynamically oriented therapy which was combined with tricyclic medication (Imipramine 75 mg.), with a complete remission of her sexual symptoms in 30 weekly sessions. On follow-up four years later, the patient, who had not taken medication since termination of treatment, reported that she and her husband had continued to enjoy frequent and mutually gratifying sexual relations. The couple had also had a child during this period.

Medication and the Process of Sex Therapy

Once we became aware of the possible coexistence of sexual dysfunction and panic disorder, it became apparent that this case was by no means unique or even uncommon.

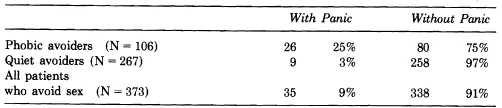

We found that 25 percent of our patients with sexual phobias and aversions also met the criteria for panic disorder, which is significantly greater than 2 percent, the estimated prevalence of this syndrome in the general population (DSM-III, 1980) (see Table 1).

Table 1

Prevalence of Panic Disorder in Patients with Sexual Avoidance†

† These patients were evaluated in our programs between 1976 and 1986.

Sig. <.001

In retrospect, this should not have been surprising. Individuals with phobic anxiety syndrome, which was Klein’s (1964) original term for panic disorder, are at high risk for developing phobic avoidances of all kinds. There was no reason to believe that sex would be an exception.

It also turned out that patients with these combined syndromes accounted for a number of puzzling treatment failures.

In our programs,2 most patients with sexual phobias and aversions receive psychodynamically oriented sex therapy. This method combines therapeutically controlled exposures to the feared sexual situation to extinguish the patient’s irrational fear of sex with brief psychodynamically oriented therapy to provide insight into deeper conflicts. Sexually phobic and aversive patients who have a normal capacity for anxiety ordinarily show an excellent response to this approach. However, patients with underlying panic disorder find treatment stressful and they tend to resist. They generally do not experience the expected desensitization effect, nor does insight into their underlying neurotic conflicts seem to facilitate their progress. Their fears are simply too intense. Instead of bringing improvement, sex therapy may actually aggravate their sexual panics and intensify their compelling urge to avoid sex.

For the last five years we have been using antipanic medication together with sex therapy on a regular basis for patients with sexual complaints and panic disorders. We have found that these drugs can protect the patient from panic attacks during the treatment process and frequently make it possible for them to cooperate with and benefit from sex therapy.

It was not our purpose to prove that antidepressant medication is indicated for sexual panic states. The efficacy of the tricyclic antide-pressants (TCDs), monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) and alprazolam in the treatment of panic disorders has been well documented, and we did not feel it necessary to conduct additional controlled double-blind studies on the effects of these drugs on our population.

The use of medications that were known to block panic attacks in conjunction with sex therapy for patients who have both diagnoses was simply an application of this proven therapeutic modality to the area of sexuality in our attempt to provide more effective treatment for these difficult patients.

For many years, there had been a sharp split between behavioral and psychodynamically oriented clinicians about the causes and treatment of psychosexual disorders. But shortly after the integrated sex therapy methods were introduced in the 70s, it became clear that behavioral and dynamic methods actually complement and enhance each other. The combined approach came to be regarded as a major breakthrough, and the old fallacious controversy was laid to rest.

A comparable and equally false dichotomy has historically existed between psychological and biological psychiatry. The controversy has now diminished in the area of the psychoses, and today there is general consensus among health professionals that medication is indicated and beneficial for patients with schizophrenic psychoses and major affective disorders. However, the medication versus psychotherapy controversy is still very much alive with regard to anxiety, which has long been considered the province of the psychotherapist.

One source of these pointless arguments is that clinicians trained in psychopharmacology and those with psychological orientations do not understand each other’s language and find it difficult to communicate. Scientifically minded psychopharmacologists are committed to relieving their patients’ painful symptoms as rapidly and directly as possible. They are not, as a rule, interested in psychodynamics, nor in the subtle emotional nuances of the patients’ experiences, which they regard as immaterial to their recovery. Psychiatrists with biological orientations tend to dismiss the accumulated wisdom of psychoanalysis as unscientific and of no proven benefit to patients, mainly, I think, because few have taken the trouble to study these theories in depth.

On the other hand, sensitive and humanistic analysts and therapists focus on the patient’s feelings and inner experiences. They regard the quality of the therapeutic relationship as a crucial element for the success of treatment. Many of these dynamically oriented clinicians have no use for the biological approaches, and are critical of what they consider mechanical and manipulative solutions to human problems. Their failure to appreciate the potential benefits of psychoactive drugs is generally the result of their lack of understanding of the biological aspects of human behavior and their erroneous beliefs about the harmful effects of the new medications.

Since we started in 1970, we have worked with more than 2,000 patients and couples with sexual dysfunctions at the Human Sexuality Clinic at Payne Whitney and at our private center for the evaluation and treatment of sexual disorders in Manhattan.

Most patients with sexual disorders have received brief psychodynamically oriented sex therapy.3 In the beginning we rarely used psychoactive drugs, but by 1980 we had added antipanic medication on a regular basis to the treatment regimen of patients with sexual dysfunctions who also had panic disorders.

During the past 10 years we have treated 51 patients with these dual syndromes with sex therapy in conjunction with antipanic medication. We were thus in a unique position to observe the effects of antipanic drugs on the various aspects of psychosexual therapy, and to compare the process of therapy before and after we began using these drugs.

Our experience leaves little doubt that the arguments between the psychopharmacologic and psychotherapeutic approaches are based on false premises. When viewed from a psychodynamic perspective, and also with the dynamics of the couple’s relationship in mind, it becomes quite clear that both psychotherapy and medication have an important but entirely different function in the treatment of sexual anxiety states and that both are needed to help patients with drug-responsive sexual anxiety. Neither the most astutely devised behavioral program nor the most insightful, sensitive psychoanalysis can possibly normalize a brain’s biologically abnormal alarm system. Yet medication alone can never take the place of skilled, caring and empathic psychotherapeutic intervention. Protecting a patient from panic chemically does not automatically cure long-standing avoidance of living and loving, nor can drugs by themselves resolve inner sexual conflicts or marital difficulties. However, under certain circumstances the effects of these agents enable previously resistant patients to respond to the sex therapy process.

When used for the appropriate indications, within an eclectic conceptual framework that acknowledges the biologic as well as psychodynamic aspects of sexual psychopathology, the psychological and medical therapies often act with surprising synergy. Immense benefits can result from combined treatment.

Antipanic drugs are valuable adjuvants for the behavioral modification of the sexual symptoms that are associated with phobic-anxiety states. Our experience suggests that these agents could also potentiate the effectiveness of the dynamic therapies for fostering positive changes in the patient’s personality and basic improvements in the relationships of some of these couples.

The old prejudices are irrational and do a disservice to patients and couples who could benefit from a combined approach. I believe that the integrated use of drugs and dynamic therapy is the treatment of the future for patients with drug-responsive emotional syndromes.

The antipanic drugs have given us a new weapon for our struggle against sexual inadequacy that enhances the therapeutic effectiveness of both medical and non-medical clinicians who work with patients and couples with sexual disorders. For these reasons, it is ...