eBook - ePub

Crack Cocaine

A Practical Treatment Approach For The Chemically Dependent

- 322 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Using first-hand experience, the author presents a practical treatment approach, originally designed for crack patients, but generally applicable to chemical dependency problems. It also explains the social, biological and psychological factors in crack addiction and various barriers to treatment.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Crack Cocaine by Barbara C. Wallace in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Addiction in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

II

Theory and Implications for Clinical Technique

4

Pharmacological Approaches

A biopsychosocial model of crack addition assists in the identification of probable etiological factors in the development of an addiction. Biological, psychological, and social factors may prove to be etiological factors from which corresponding treatment interventions logically arise. In this way, we may arrive at a theoretical rationale for specific kinds of treatment interventions. This approach follows Marlatt (1988), who asks, “Is it possible to match treatment modality with specific etiological factors…?” (p. 476). The selection of specific treatment modalities that address biological, psychological, or social etiological factors may logically follow from a consideration of etiology. Knowledge of etiology therefore may facilitate matching patients to specific treatments. One of the guiding principles behind the use of a biopsychosocial model of addiction is that careful assessment determines which specific treatment interventions are necessary for individual patients (Donovan & Marlatt, 1988). However, before considering assessment (Chapter 10) and the process of matching patients to treatment modalities, we must present the theoretical rationale for the use of treatment interventions.

A discussion of the theoretical rationale for utilizing pharmacological adjuncts with crack smokers follows from recognizing biological variables that may play a role in the etiology of crack addiction. In Chapter 1, we saw that the pharmacological and neurological actions of crack cocaine on the human brain are partly responsible for the development of compulsive crack smoking and, therefore, for the development of addiction, or crack dependence. Using our knowledge of etiological factors as a rationale for treatment, it follows that the neurochemical disruptions created in the brain of the crack user suggest the necessity of using pharmacological adjuncts in the treatment of the addiction.

Why Use Pharmacological Adjuncts?

It cannot be assumed that all patients will require the use of pharmacological adjuncts. However, for crack patients presenting with crack dependence and sharing many common features, routine consideration of pharmacological adjuncts may be important to maximize the chances of a successful recovery. Having noted in Chapter 3 the kind of daily or nearly daily high-dose crack smoking we observed as predominating among the patients in Wallace’s (1990b) sample, we can appreciate how chronic or compulsive crack smokers likely have instigated neurochemical changes in their brain function, and also have probably neglected their diet and nutrition. Even though scientific knowledge of brain neurochemistry and of brain and cocaine interactions is limited, a rationale for utilizing pharmacological adjuncts exists in the literature. The use of different strategies in restoring and addressing neurochemical disruptions in brain function caused by crack cocaine reflects the state of the relatively new and experimental treatment modality of providing chemotherapies, medications, or pharmacological adjuncts to crack and cocaine patients. Nonetheless, a biopsychosocial model of crack addiction appreciates the importance of experimental pharmacology and the rationale for treating crack dependence with pharmacological adjuncts. However, we must also recognize that the variety of approaches to utilizing pharmacological adjuncts, diverse strategies, hypotheses, and research approaches all reflect the need for more research in this experimental field. The urgency of the crack-cocaine epidemic necessitates that this research be done and that patients benefit from available knowledge by receiving safe and promising treatments as suggested by research findings.

Pharmacological Adjuncts as Relapse Prevention

The provision of pharmacological adjuncts can actually be thought of not only as a treatment intervention, but also as a form of relapse prevention. Pharmacological adjuncts may assist patients in maintaining abstinence. For example, early departure from a range of treatment modalities (inpatient, outpatient, residential) may reflect patients’ exercising their right to sign out of facilities (often against medical advice) or to terminate participation in treatment in order to satisfy powerful cravings for crack. The field of chemical-dependency treatment may improve treatment outcome by assessing patients for the provision of pharmacological adjuncts, while keeping pace with experimental research findings that prove which adjuncts are best for which kinds of patients. Several perspectives on and approaches to the use of pharmacological adjuncts prevail in this field, which is admittedly in its infancy, and merit examination.

Use in Specific Phases of Recovery

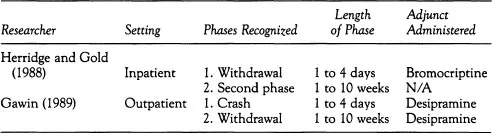

Herridge and Gold (1988) recognize that pharmacological adjuncts may play a specific role in the early withdrawal phase when a patient is attempting initial abstinence from crack cocaine, and another role in the next two to three months of early abstinence. They challenge the widely held belief that “in the early phase of cocaine withdrawal the symptoms are mild and do not require treatment” (p. 238). However, they also argue the importance of an alternative view, which recognizes that drug craving in particular—which is a “powerful brain-driven force that tends to make patients behave in whatever way will insure the acquisition and ingestion of cocaine” (p. 238)—justifies the use of pharmacological adjuncts in the withdrawal phase. This first phase may last up to four days, and also includes symptoms of agitation and anorexia, followed by fatigue, exhaustion, depression, hyperphagia, hypersomnia, and diminished craving. The use of pharmacological adjuncts in this early phase of withdrawal may be critical to prevent patients from signing out of treatment and resuming their use of crack cocaine.

Following the conceptualization of Herridge and Gold (1988), we might view the use of pharmacological agents as for either the four-day withdrawal period or the second phase following withdrawal, which may last up to ten weeks. While mood and sleep normalize in the second phase, a powerful craving for cocaine may still arise, especially in response to stimuli associated with cocaine use. There remains a great danger of relapse during this second phase in which crack cravings may spontaneously reoccur or may be triggered by environmental cues. Since antidepressants require three weeks to take effect, Herridge and Gold recognize the value of the antidepressant desipramine in reducing cravings in the second phase (p. 238), citing reports that it can reduce cocaine cravings and facilitate abstinence (Tennant, Rawson, & McCann, 1981).

Gawin (1989) refers to the four-day withdrawal period as the “crash,” while Herridge and Gold (1988) call it the withdrawal period. Gawin likens the crash to a hangover characterized by agitation. Also, Gawin views the first phase of a crash as followed by what he refers to as a one- to ten-week withdrawal phase; this is the same “up to ten week” second phase to which Herridge and Gold refer, although their terminology differs. Within Gawin’s system, after the four-day crash terminates, anhedonia gradually begins to appear and cravings begin to become a problem. At this point, the withdrawal and anhedonia characteristic of this second phase involve a biological component, according to Gawin. Patients feel boredom in association with the anhedonia, do not experience normal pleasures, and find life to be empty, shallow, and pale (Gawin, 1989).

Based on animal research studies with rats, Gawin follows a strategy whereby the provision of antidepressants is geared toward normalization of the brain reward center, which, as explained in Chapter 1, is deleteriously affected by crack use. Gawin sees the administration of antidepressants during the one- to ten-week withdrawal phase as facilitating the discontinuation of cocaine use, decreasing cravings, and permitting the achievement of abstinence. In addition, Gawin recognizes, as do Herridge and Gold, the great danger of relapse in response to conditioned cues, so he cites an indefinite time period of a third phase, which he calls the extinction phase—suggesting that extinction to conditioned cues goes on indefinitely. Although Herridge and Gold and Gawin use different terminology and language, they describe a period of initial abstinence lasting up to four days and a second period of continuing symptoms that lasts up to ten weeks.

Table 4.1

Phase-Specific Pharmacological Approaches

Phase-Specific Pharmacological Approaches

During the early initial period of withdrawal, Herridge and Gold (1988) recommend the use of bromocriptine. For the second period of prolonged abstinence (or avoiding relapse), Gawin recommends the use of desipramine, whereas Herridge and Gold concur in recognizing the potential value of this particular approach during the second phase after the initial withdrawal.

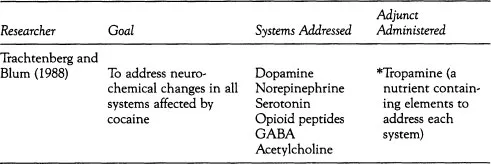

Individual Classes of Agents vs A More Complete Approach

Trachtenberg and Blum (1988) refer to four classes of medications and nutritional/neurochemical agents that are in current use: antidepressants (desipramine, imipramine, trazodone, phenelzine, lithium); antipsychotics (chlorpromazine, fluphenazine); antiparkinsonian agents (bromocriptine, amantadine, levodopa); and amino acids (tyrosine, tryptophan), and amino-acid, vitamin, and mineral mixtures. Instead of advocating the use of just one class of agents, Trachtenberg and Blum suggest a more complete approach and aim to address neurochemical changes involving the functioning not only of dopamine, but also of norepinephrine, serotonin, opioid peptides, GABA, and acetylcholine. They also recognize that chronic cocaine use results in alterations to the number and affinity of transmitter receptors as well as the anatomical connections involving these neurons (Banerjee et al., 1979; Borison et al., 1979; Chanda, Sharma, ck Banjeree, 1979; Taylor, Ho, & Fagen, 1979). Moreover, Trachtenberg and Blum appreciate that these profound alterations can require prolonged recovery (Gold & Washton, 1987; Nunes & Rosecan, 1987).

Trachtenberg and Blum recognize that most contemporary approaches focus on only some of the alterations in brain neurochemistry when treatments address only single neurotransmitter systems and presume that there is an adequate supply or prompt restoration of all the other neurotransmitter systems. Trachtenberg and Blum, therefore, argue for a more complete approach that focuses on each of the modified neurotransmitter systems. They advocate precursor amino-acid loading and enkephalin/endorphin elevation to facilitate the restoration of critical neurotransmitter deficits known to occur in cocaine abusers. They note evidence suggesting that Tropamine (Matrix Technologies, Inc.), an example of precursor amino-acid loading, effectively reduces cravings (Blum et al., 1988); they suggest a potential role, in particular, for pharmacological adjuncts that address multiple neurochemical changes—and thus provide a more complete approach to restoration of cocaine-induced neurochemical changes. The use of such adjuncts also constitutes an important relapse-prevention effort in their view.

Table 4.2

A More Complete Pharmacological Approach

A More Complete Pharmacological Approach

Psychotropic Medication for Psychiatric Illness

Another prominent perspective involves the use of psychotropic medication to address preexisting or coexisting psychiatric illness. From this perspective, Rosecan and Nunes (1987) discuss the use of antidepressants, lithium, methylphenidate (and other stimulants), bromocriptine, and amino acids. The use of medication in chronic cocaine abusers follows the rationale that they suffer a greater prevalence of mood disorders (depression, manic depression, and cyclothymia) than other substance abusers. While Rosecan and Nunes recognize that accurate diagnosis of affective illness is difficult to make with active cocaine users or those in withdrawal, they cite the fact that chronic cocaine use may intensify preexisting affective illness, that cocaine may be depressogenic for some patients, and that neurochemical changes produced by chronic cocaine use appear similar to the changes found in depression as part of the rationale behind the use of medication. According to their perspective, lithium is indicated in the treatment of cyclothymia or manic-depressive illness. Where evidence of major depression exists, the use of antidepressants is indicated. Methylphenidate or other stimulants are indicated for ADD, and antipsychotic (neuroleptic) medication is indicated for the treatment of paranoid or other psychosis that does not resolve within 24 hours of cessation of cocaine use. They recognize that, from a psychiatric perspective, the only indication for the use of bromocriptine involves refractory cases of cocaine abuse where relapse is a problem; and the indication for the use of amino acids is unclear from this medication of preexisting or coexisting psychiatric illness perspective. Most important, Rosecan and Nunes (1987) validate that craving may have neurochemical correlates that involve the depletion of neurotransmitters and receptor supersensitivity (pp. 258–260).

Table 4.3

Medication-for-Psychiatric-Illness Approach

Medication-for-Psychiatric-Illness Approach

Rosecan and Spitz’s (1987) Approach | ||

Disorder Addressed | Medication/Pharmacological Adjunct Administered | |

1. Cyclothymia/manic depression | 1. Lithium | |

2. Major depression | 2. Antidepressants | |

3. Paranoid psychosis that does not remit within 24 hours of last cocaine use | 3. Antipsychotics | |

4. Refractory cases of cocaine; relapse problem | 4. Bromocriptine | |

5. Unclear indication for use | 5. Amino Acids | |

An Integrated Perspective and Rationale for the Use of Pharmacological Adjuncts

As we saw in Chapter 2, data on the presence of mood disorders in cocaine users are fraught with problems. Diversity in the prevalence of psychopathology may best characterize research findings on the presence of mood and personality disorders. With chronic cocaine use, which best characterizes the use patterns of compulsive crack-cocaine smokers, the neurochemical disruptions tend to be even more deleterious. Also, with crack smokers, craving that may be neurochemically based has usually been a factor in the escalation from recreational-use patterns to cocaine abuse or dependence. Cravings tend to be a more common problem for crack smokers—with an associated high risk of relapse—than are documentable mood disorders.

If we integrate the perspectives of Herridge and Gold (1988), Trachtenberg and Blum (1988), and Rosecan and Nunes (1987), we may arrive at a rationale for the use of pharmacological adjuncts with crack-cocaine smokers. Most patients meeting the criteria for cocaine dependence have engaged in chronic crack smoking at a dose and frequency that may be quite high, as the data of Wallace (1990b) presented in Chapter 3 suggest. For these patients, a critical treatment intervention may be the provision of pharmacological adjuncts that facilitate achieving a stable state of abstinence. Following Herridge and Gold, it seems logical to incorporate the concept of a stage of withdrawal lasting up to four days and a second phase of ten weeks or two to three months when chances of relapse are greatest.

The author suggests the following phases of recovery from crack.

1. Early abstinence/withdrawal phase. This phase involves the initial period, in which patients are either in a state of withdrawal, or the period in which they may undergo a formal detoxification. This is a period of early abstinence from drugs. The first period can be seen as lasting up to 14 days. Chances of departure from treatment and immediate relapse to chemical use are very high during this time.

2. Phase of prolonging abstinence. This second phase involves the period after initial withdrawal when individuals attempt to prolong the time for which they are able to remain abstinent and avoid relapse. It lasts up to the first six months following the cessation of drug use. This period is typically marked by at least one “slip” or relapse episode, especially when relapse-prevention education is not an intensive part of treatment. Treatment efforts may effectively reduce chances of relapse during this period when patients are very vulnerable.

3. Pursuing lifetime recovery. Beyond the first six-month period of prolonging abstinence, a third period extends to include anywhere from one to several years or a lifetime of recovery. During the first year of recovery in particular, a danger of relapse to crack or the development of an addiction to other drugs exists. A risk of relapse following from the spontaneous reemergence of cravings, or cravings arising on the anniversaries of past large cocaine use (New Year’s Eve) or in response to an individual’s conditioned cues for chemical use (a reward for hard work, a celebration) make the first few years of recovery rather hazardous as well. Decisions rega...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- I. Crack: The Nature of the Treatment Challenge

- II. Theory and Implications for Clinical Technique

- III. Crack-Treatment Models

- IV. Clinical Technique in the Assessment Phase

- V. Clinical Technique In The Treatment Phase

- References

- Author Index

- Subject Index