eBook - ePub

The Evolution of the Grand Tour

Anglo-Italian Cultural Relations since the Renaissance

- 432 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The Grand Tour has become a subject of major interest to scholars and general readers interested in exploring the historic connections between nations and their intellectual and artistic production. Although traditionally associated with the eighteenth century, when wealthy Englishmen would complete their education on the continent, the Grand Tour is here investigated in a wider context, from the decline of the Roman Empire to recent times.

Authors from Chaucer to Erasmus came to mock the custom but even the Reformation did not stop the urge to travel. From the mid-sixteenth century, northern Europeans justified travel to the south in terms of education. The English had previously travelled to Italy to study the classics; now they travelled to learn Italian and study medicine, diplomacy, dancing, riding, fencing, and, eventually, art and architecture. Famous men, and an increasing proportion of women, all contributed to establishing a convention which eventually came to dominate European culture. Documenting the lives and travels of these personalities, Professor Chaney's remarkable book provides a complete picture of one of the most fascinating phenomena in the history of western civilisation.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Evolution of the Grand Tour by Edward Chaney in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

I

British and American Travellers in

Sicily from the Eighth to the

Twentieth Century

Sicily from the Eighth to the

Twentieth Century

To have seen Italy without having seen Sicily is not to have seen Italy at all, for Sicily is the clue to everything.J.W. von Goethe, Italian Journey: 1786–1788, transl.W.H. Auden and E. Mayer (London, 1962), p. 240

ON 18 APRIL 1955, less than a fortnight after resigning as Prime Minister, the 80-year-old Sir Winston Churchill wrote to the young Queen Elizabeth II. Presumably because he wanted somewhere relatively remote but essentially civilized, somewhere steeped in history, warmed and well-lit by the Mediterranean sun (so he could paint out of doors), he had headed straight for Sicily and for Siracusa in particular. He informed Her Majesty that:

The historical atmosphere of Syracuse grows perceptibly upon me and my companions here as the days pass. Our hotel rises out of the sinister quarries [Fig. 2] in which six thousand Athenian prisoners of war were toiled and starved to death in 413 BC, and I am trying to paint a picture of a cavern's mouth near the listening gallery whose echoes brought secrets to the ears of Dionysius. All this is agreeable to the mental and psychological processes of laying down direct responsibility for the guidance of great affairs and falling back upon the comforting reflection ‘I have done my best’.

Not much is known of what was happening in Britain in 413 BC; no doubt very little compared with what was undoubtedly happening in Athens and Syracuse, then the two greatest cities in (at least) the western world. The earliest British accounts of Sicily date from more than a millennium later and are very sketchy. The first I have found was written in Latin by a nun to whom the aged St Willibald dictated his memoirs. Unfortunately, while he (and perhaps she) elaborated interestingly on the subjects of Syria, Jerusalem and Constantinople in the narrative of his pilgrimage, posterity was left to guess at most of what he saw during the three weeks he spent in Catania in 723, or his overnight stop in Syracuse. Only the Mediterranean volcanoes seem to have aroused any real enthusiasm in him. Even when he describes the miraculous powers of Catania's Sant' Agata (whom he misremembers as St Agnes), he is interested primarily because those powers included the capacity to halt Etna's lava flow. On his return journey from the east six years later, it was the island of Vulcano which fascinated him as it had fascinated Thucydides more than a millennium earlier:

Thence they sailed to the island Vulcano: there is the inferno of Theodoric. And when they arrived, they went up from the ship to see what the inferno was like. Willibald was very curious to see what was inside the inferno, and would have climbed to the mountain top above it: but he could not. For the ashes blew up from the black hell and lay piled in heaps on the edge and … prevented Willibald's ascent. But he saw the flames belching black and terrible and horrifying from the pit like resounding thunder, and he watched the great flame and the vapor from the smoke mounting terribly but awfully on high. That pumice which writers use he saw rising from the inferno and blown out in flame and hurled into the sea and thence cast ashore and men take it up and carry it away.

For most of the rest of the Anglo-Saxon period Sicily was ruled by the Saracens and there was even less ‘English’ contact with the island. In the wake of the Norman conquests of both England and Sicily in the latter part of the eleventh century, however, Anglo-Sicilian relations flourished as never before nor since. In particular, Anglo-Norman scholars and administrators of all kinds visited or established their careers in Sicily, jostling for promotion with rival Italian, Greek and Arab bureaucrats. Most eminent among those who made the long journey in the first half of the twelfth century were John of Salisbury (the most learned classical writer of the Middle Ages), Adelard of Bath (pioneer of Arab studies), John of Lincoln (Canon of Agrigento), Robert of Selby (who became King Roger's Chancellor) and Master Thomas Brown (who after serving in Roger's civil service for 21 years — organizing the Sicilian treasury along English lines — returned home to help Henry II organize Angevin England, using his Sicilian experience). Under Roger's ‘Bad’ son, William I, and ‘Good’ grandson, William II, in the second half of the century, the Anglo-Sicilian connection was at its strongest. The international reputation of the court at Palermo for cosmopolitan culture and good career prospects attracted learned prelates such as Richard Palmer, eventually Archbishop of Messina, whose epitaph is still in his Cathedral (albeit somewhat damaged by the 1908 earthquake) and Robert Cricklade, Chancellor of the University of Oxford and biographer of Thomas Becket. The somewhat sinister Walter ‘Ophamil’, who rose to become Archbishop of Palermo, and his brother, Bartholomew, who succeeded him as Archbishop in 1190, do not seem to have been English, the quaint notion that their surname was derived from ‘of the Mill’ being now discredited.

In the early years of William II's reign, during the period leading up to Becket's assassination in December 1170, rival emissaries from the opposed camps of the English King and this ‘turbulent’ Archbishop of Canterbury arrived in droves, each trying to enlist powerful Sicilian support for their respective causes. Together with Louis VII of France, Becket was particularly opposed to the proposed marriage between the young King of Sicily and a daughter of Henry II. In the event, not even his assassination and subsequent canonization prevented this great alliance, Henry's profession of innocence and his public penance persuading the Sicilians to forgive and forget the sacrilege at the same time they were naming churches and decorating their cathedrals with mosaics commemorating the new English saint. The tall figure of St Thomas in the apse of Monreale dates from the 1180s, but approval to convert a mosque at Catania into a church of St Thomas of Canterbury was granted as early as January 1179. Later, Marsala would even dedicate its Cathedral to the English saint.

John of Oxford, Bishop of Norwich, was despatched by Henry II in the summer of 1176 to finalize arrangements for the marriage of his third daughter, Joanna, to King William and we have a record of his difficult journey, at first ‘troubled by a great shortage of bread and of fodder’, then by danger from the Lombards who supported an anti-pope, and eventually by the ‘excess of heat’, the rocks and whirlpool of Scylla and Charybdis, where ‘the sea frequently turns upside down in an instant’, and the ‘notable filth of the oarsmen [which] produced nausea’. The royal progress of the IO-year-old Princess herself, starting from Southampton on 26 September 1176, was evidently more comfortable, her nausea being brought on merely by the motion of the ship. She was escorted initially by her eldest brother, Henry, and then by another brother, Richard Coeur de Lion, later to make the journey to Sicily himself on his way to the Crusades. On reaching the port of St Gilles, at the mouth of the Rhône, she was met by 25 of her future husband's ships. The Sicilians decided to play safe with their precious cargo, all the more so when news arrived that two ships transporting William's gifts to Henry II had foundered. They clung close to the French coast and down most of the western shore of Italy as far as Naples, at which point the Princess's seasickness necessitated continuing the journey by land most of the way down to the Straits of Messina and then due west along the north coast of Sicily, via Cefalù, to Palermo. Here the 23-year-old William met his fellow French-speaking bride at the city gates, had her mounted on one of his finest horses, and escorted her to the palace (which must surely have been the recently completed Zisa) where she and her household were to stay for the 11 days which remained until her wedding. A contemporary wrote that ‘the stars in the heavens could scarcely be seen for the brilliance of the lights’ which illuminated Palermo for the state entry. The couple were married on St Valentine's Eve 1177 and, immediately after, Joanna was crowned Queen of Sicily by ‘Emir and Archbishop’ Walter in the Cappella Palatina.

William the Good died in 1189, without a legitimate heir and genuinely mourned by most of his subjects, perhaps because they sensed that Sicily's prosperity might not endure under his compromise successor, Tancred. William's tutor, Peter of Blois, had indeed left the island 20 years earlier, urging his friend, Richard Palmer, to likewise ‘Flee … the mountains which vomit flame’ and the land which ‘devours its inhabitants’.

In the spring of 1191, Catania was the scene of an extraordinary meeting between Queen Joanna, her brother Richard I (who had just caused havoc by occupying Messina), his mother, the 69-year-old Eleanor of Aquitaine and his bride-to-be, Berengaria. Despite the recent prohibition against Crusading women he took her with him and his sister to the Holy Land. Though there is no evidence as to what Richard and the English crusaders thought of Sicilian volcanoes, there is ample negative testimony on ‘the wicked citizens, commonly called Griffons, … many of them born of Saracen fathers’. The Itinerarium Ricardi admits that ‘the city of Messina … is filled with many varieties of good things in a region which is pleasant and most satisfying … It stands first in Sicily, rich in essential supplies and in all good things: but it has cruel and evil men.’ Clearly both factors lay behind the English occupation of Messina. Three years later the Western Emperor, Henry VI of Hohenstaufen, invaded Sicily with the help of 50 ships taken as ransom for Richard's release from post-crusading captivity and on Christmas Day 1194 he was crowned King of Sicily in Archbishop Walter's Cathedral in Palermo. Sicily would flourish again under Henry's son Frederick II, ‘Stupor Mundi’, but the golden age of its intimacy with that Norman-dominated island in the north was over, even if the continued presence of outstanding individuals such as Gervase of Tilbury and Michael Scot perpetuated some of the traditional cultural connections.

Though the Spaniard, Pero Tafur, was capable of providing posterity with a coherent description of the cities of Sicily in the 1430s, it was not until the first half of the sixteenth century that we notice signs of the Holy Land pilgrimage being replaced by something resembling the Grand Tour and the first reasonably coherent English accounts of Sicily. In general, the 1517–18 diary of the priest, Richard Torkynton, depends heavily on the printed Pylgrymage of Sir Richard Guylforde Knygth of 1511. Guylforde, however, seems not to have stopped in Sicily and died in Jerusalem so we can assume that the little Torkynton says on this subject is more or less original.

Returning from the Holy Land, via Cyprus, Rhodes and Corfu, ‘the fairest ground that ever I saw in my life’, Torkynton and his party arrived after much difficulty at Messina on Saint Gregory's Day (March) 1518 and spent five days relaxing in the city:

Thys Missena, in Cecyll, ys a fayer Cite and well wallyd wt many fayer towers and Div[er]se castell, the fayrest havyn for Shippes that ev I saw, ther ys also plente of all maner of thyngs that ys necessari for man, except clothe, that ys very Dere ther, ffor englyssh men brynge it theyr by watyr owt of … Enlong [England], it ys a grett long wey.

Hakluyt tells us that the English wool merchants made regular journeys between London and Sicily in the early sixteenth century but this is a rare contemporary reference to the trade, though it was not long before there were English consuls in Trapani and Messina.

Richard Torkynton must have been one of the last pilgrims to visit the Holy Land whilst it was still governed by the relatively tolerant Egyptian Mameluke dynasty. While he was on his way home, Jerusalem fell to the Ottoman Sultan Selim I and henceforth Palestine was ruled by the Turks. Increasingly., Rome and Loreto became the two major substitute destinations for pilgrims, and though the merchants continued to trade in Sicily and southern Italy, the south was visited, if at all, out of curiosity. The ‘curiositas poetica’, which Petrarch had feared might replace ‘devotione catolica’ as early as the mid-fourteenth century, became ever more dominant during the Renaissance and eventually triumphed in the mentality which manifested itself in the Grand Tour. That Sicily never fully established itself as an essential ingredient of a Grand Tour itinerary is for the present purposes all to the good. Those who bothered to break off or extend their tours to include it, tended to be the more imaginative, eccentric or adventurous, and thus, where they record their journeys, reveal far more than the conventional tourist about both themselves and the fascinating island they were visiting.

Much the most remarkable of the surviving sixteenth-century accounts of Sicily is that to be found in the autobiographical Booke of the Travaile and Lief of me Thomas Hoby which, despite its intrinsic interest and its importance as the work of the translator of Castiglione's Il Cortegiano, remained unpublished until 1902 and is still inadequately known [Fig. 3]. On 11 February 1550, having explored Naples and its environs with a group of English friends, the 20-year-old Hoby decided to set off on his own, ‘throwghe the dukedom of Calabria by land into Cicilia, both to have a sight of the countrey and also to absent my self for while owt of Englishemenne's companie for the tung's sake.’

From Reggio, recently ravaged by the Turkish pirate-cum-admiral, Barbarossa, Hoby crossed over to Messina which he considered ‘on[e] of the fairest portes in Europe’. He was equally impressed by both its ancient and modern features; on the one hand by ‘the heades of Scipio and Hannibal, when they were yong menn, in stone’, and on the other by the recently rebuilt royal palace, the three Spanish castles and, most recent of all, the exquisite Orion fountain upon which the great Florentine sculptor, Giovanni Montorsoli, was then still working:

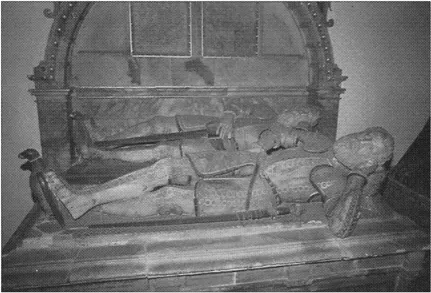

3 Sir Thomas Hoby (foreground) and his half-brother Sir Philip: the Hoby tomb at Bisham Church, Berkshire (c.1566). [E. Chaney]

For a new worke and that not finisshed at my being there, I saw a fountaine of verie white marble graven with the storie of Acteon and such other, by on[e] Giovan Angelo, a florentine, which to my eyes is on[e] of the fairest peece of worke that ever I sawe. This fountain was appointed to be sett uppe before the hige churche where there is an old on[e] alreadie.

In 1563 Hoby set up his own fountain at Bisham Abbey, while at Nonsuch., the Ovidian Actaeon story features prominently in the fountain sculpture created by the Italophile 12th Earl of Arundel (whom Hoby entertained to dinner in 1560) [Fig. 4] and his son-in-law, Lord Lumley. In 1566, either Hoby or his widow — stranded in France when he died — commissioned a tomb featuring Italianate effigies of him and his brother which were in advance of any other contemporary ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- List of illustrations

- Introduction

- 1. British and American Travellers in Sicily from the Eighth to the Twentieth Century

- 2. Early Tudor Tombs and the Rise and Fall of Anglo-Italian Relations

- 3. Quo Vadis? Travel as Education and the Impact of Italy in the Sixteenth Century

- 4. The Grand Tour and Beyond: British and American Travellers in Southern Italy, 1545–1960

- 5. Robert Dallington's Survey of Tuscany (1605): A British View of Medicean Florence

- 6. Documentary Evidence of Anglo-Italian Cultural Relations in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries

- 7. Inigo Jones in Naples

- 8. Pilgrims to Pictures: Art, English Catholics and the Evolution of the Grand Tour

- 9. Notes towards a Biography of Sir Balthazar Gerbier

- 10. English Catholic Poets in mid-Seventeenth-Century Rome

- 11. ‘Philanthropy in Italy’: English Observations on Italian Hospitals, 1545–1789

- 12. Milton's Visit to Vallombrosa: A Literary Tradition

- 13. George Berkeley's Grand Tours: The Immaterialist as Connoisseur of Art and Architecture

- 14. Epilogue: Sir Harold Acton, 1904–94

- 15. Bibliography: A Century of British and American Books on the Evolution of the Grand Tour, 1900–2000

- Index