- 864 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Attention and Performance Viii

About this book

First published in 1980. This is a volume of the proceedings of the Eighth International Symposium on Attention and Performance held in Princeton, New Jersey, USA, from August 20th to 25th 1978.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Association Lecture: Functional Aspects of Information Processing

W. R. Garner

Yale University

New Haven, Connecticut

United States

Yale University

New Haven, Connecticut

United States

ABSTRACT

Functional aspects of information processing are discussed, with function having three different but related meanings. First, function is contrasted with structure, and such functional properties as expectancy, attention, effort, and state and process limitation are shown to differ from the primary structural construct of information processing stages. Second, function is a presuppositional aspect of information processing experiments, and these presuppositions, while keeping the experimental effort within bounds, must be considered as operations that converge to theoretical constructs as much as the experiments themselves do. Third, functional measurement decreases the importance of time as an absolute metric, thus exchanging for the power of absolute time a flexibility of interpretation which will allow methodological constructs such as additive and subtractive factors logic to survive experimental inconsistencies.

Introduction

In this chapter I discuss several substantive and methodological issues that I see as important in the study of human information processing, and these all relate to the idea of function in information-processing research. At Attention and Performance VI, A. F. Sanders (1977) spoke on structural and functional aspects of the reaction process, and some of the things I mention fit comfortably onto the ideas he expressed in distinguishing these two aspects of the reaction process. Stages constitute the primary structural aspect of information processing, but I want to expand the concept of function and to elaborate some very specific issues concerning functional aspects of information processing. Three different ways in which the idea of function enters into information processing research are described. To anticipate, there is function as contrasted with stages, function as presupposition in experimental design, and function as a guideline for measurement.

Functional Processing

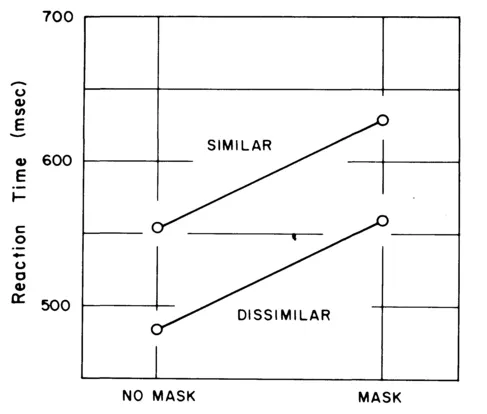

FIG. 1.1. Discrimination time for the letters A and H, similar and dissimilar, masked or unmasked (after Shwartz, Pomerantz, & Egeth, 1977).

One specific article served as the immediate impetus for what I have to discuss because it involves all three of these issues in information processing. The article is by Shwartz, Pomerantz, and Egeth (1977), and we might look at some of their data to start this discussion. Figure 1.1 shows the data outcome for just part of one of the two separate experiments they reported, but it is enough to introduce the issues. The subject's task was to identify with a vocal response either the letter A or the letter H, displayed on a cathode-ray tube. Reaction time was, of course, the primary measure of performance. The experimental design followed the additive factors logic introduced by Sternberg (1969), and the total experiment involved three factors (although, for present purposes, discussion of just the two illustrated in Fig. 1.1 is sufficient). These two factors were whether a mask of dots was present or not and whether the two letters were physically similar or dissimilar. The additive factors logic says that if two factors have additive effects, which is to say that they do not produce interaction in an analysis-of-variance sense, then we can conclude that the two factors influence separate processing stages. Given this beautiful noninteractive outcome, that is what the authors of this article concluded. Furthermore, I have no quarrel with this conclusion as long as it is restricted to the specific experimental manipulations they used, that is, to the particular type of mask and the particular method of producing a difference in similarity.

State and Process as a Functional Distinction

However, the reason for choosing these particular factors or variables to manipulate was based on the constructs of state and process limitation that I have developed over the years, and they considered the use of masking to produce a state limitation and the use of low similarity to produce process limitation. Now the problem is that I have never considered the distinction between state and process, whether used as a concept of limitation or as a concept of perceptual independence, to involve stages or structure at all. Quite the contrary, I have considered the distinction to be a functional one (Garner, 1970, 1972, 1974). So, lest all functional distinctions become inadvertently reduced or translated to stage distinctions, I would like to elaborate on the role of function in information processing, with particular emphasis for the moment on the state-process distinction.

State and Process Independence. I first used the terms state and process in 1969 in an article published with John Morton concerned with concepts of perceptual independence rather than perceptual or processing limitation. The ideas we were trying to develop were concerned with the different ways in which information-processing psychologists were using the idea of perceptual independence (although the same problems existed in other psychological realms, such as memory). We felt in particular that two quite distinct ideas were being given a common designation, to the detriment of both. One of these ideas had to do with whether processes directly interacted, and the other had to do with whether the efficiencies of two processes were correlated. Although the full elaboration of this difference can become quite complicated, the distinction at a basic level is really quite straightforward, simply involving two kinds of data analysis required for the two types of independence or correlation. Table 1.1 illustrates, with hypothetical data, the type of analysis required if we want to ask whether two separate processes interact. These processes may be channels, variables, dimensions, or any other distinction that portrays concurrent ongoing processes, processes that can function at any stage. In the table I have simply used the genera! term process, although in the original article we referred to attributes.

The important point about this table is how the rows and columns are defined, because they must be defined in terms appropriate to the nature of the processing itself. In this particular illustration we are looking at two possible responses (1 and 2) to two possible processes (A and B), and you can see that there is a correlation, thus nonindependence, between these two processes. If we know that the inputs appropriate to each of these responses or

TABLE 1.1

A Table of Data Analyzing One Form of Process Interdependencea

A Table of Data Analyzing One Form of Process Interdependencea

| Response to Process A | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 1 | ||

| Response to Process B | 1 | 30 | 20 | 50 |

| 2 | 20 | 30 | 50 | |

| 2 | 50 | 50 | 100 | |

a After Garner and Morton, 1969.

outputs are uncorrelated, then the existence of a correlation between the responses shows that there is interaction between the two processes. Many other tables could be constructed to show the exact nature of the interaction, tables that would portray data necessarily spanning several stages of information processing. One such table, for example, would show rows as input for process B, with columns being response or output for process A; and if such a data matrix showed a correlation, it would indicate that the output for process A is responsive to input for process B, at some unknown stage of processing. Thus this concept of process independence or correlation is simply not a stage concept at all but a functional concept that can span several processing stages.

Table 1.2 shows data in a different form, appropriate now for asking about state independence. Notice the different form in which the rows and columns are defined from those of Table 1.1 Now columns still refer to performance on process A and rows to performance on process B, but the separate columns or rows indicate whether performance was right or wrong. Once again there is correlation in this set of hypothetical data, but now there is no indication of a direct interaction between the two processes, only that performance on the two processes is better or worse together. It is the kind of outcome that would occur it there were fluctuations in alertness, attention, effort level, and other

TABLE 1.2

A Table of Data Analyzing State Interdependencea

A Table of Data Analyzing State Interdependencea

| Process A | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Right | Wrong | Σ | ||

| Process B | Right | 44 | 16 | 60 |

| Wrong | 16 | 24 | 40 | |

| Σ | 60 | 40 | 100 | |

a After Garner and Morton, 1969.

such functional factors, factors that could and would operate at any stage of processing.

So Morton and I intended the distinction between state and process independence to be applicable to any or all stages of processing, with the concepts of state and process themselves being orthogonal to each other. The distinction between the two was unequivocally a distinction of function and not a distinction of structure or stages. With this particular distinction, the term function actually has two possible meanings. It can imply function in the sense that Sanders distinguished function from structure, and of course I am discussing stages because that is the major structure notion having currency now. But function can also imply the way data are treated, and in that sense the difference between state and process is almost a simple operational distinction.

State and Process Limitation. I later (Garner, 1970) extended the concepts of state and process to involve limitation, not just interaction. Norman and Bobrow (1975) also explored distinctions between types of limitation, differentiating in particular between data and resource limitations; although their distinctions are related to those I have made between state and process, they are far from identical and are actually more in line with stage distinctions than with functional distinctions. In my own case, even while shifting from ideas of independence to those of limitation, I clearly intended the distinction to be functional and not structural.

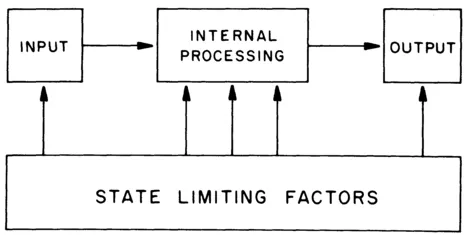

FIG. 1.2. The relation between process and stage limiting factors.

The best way I know of differentiating between state and process limitations is shown in Fig. 1.2. At the top I have indicated the minimum sequence of events that can be involved in an information-processing act: an input stage, an internal-processing stage, and an output stage. It is this sequence which directly involves the processing of information, and any limitation which directly affects the processing of information as specified by the task requirements is a process limitation. Such limitations might be inadequate stimulus differentiation if at the input side of the sequence or an undifferentiated response system if at the output end, or any limitation on encoding, memory, retrieval, comparison, or other internal-processing stage.

State limiting tactors are any factors that affect the ability of the organism to carry out the specified information-processing task but are not themselves directly relevant to that task. Thus if the organism is asleep, that is a state limiting factor; so also would be inadequate energy at the input end or weak fingers at the output end if the output is to be a lever push.

The point that must be understood is that process limitations can occur at any stage in processing and so also can state limitations. What differentiates the two is not stages but function with respect to the task as defined by the experimenter for the particular experiment. Thus when a stimulus has inadequate energy, a state limitation is produced if the task is one of discriminating between two letters, as in the experiment by Shwartz et al. (1977). If, however, the task requires discrimination of a stimulus with some energy from one with no energy, then energy or its lack would be a process limiting factor. Process limitation and state limitation are orthogonal functional concepts, and if a particular experimental outcome justifiably seems to imply stage differentiation, then that is because by chance or otherwise one type of limitation was applied to one stage and another type of limitation was applied to another stage. An outcome indicating stage differences should not be used to imply that there are not very important functional differences to be considered, and it is important not to lose sight of these functional differences. In other words, we should continue to ask not only the when of stages but also the what and how of functions.

Because I have written on the functional role of state versus process limitation before (Garner, 1970, 1972, 1974), I do not attempt an extended treatment of the problem here. However, I shall note that my original and later uses of the distinction between state and process limitation had to do largely with the function of different types of redundancy in coping with inadequate information processing...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Contributors and Participants

- Preface

- 1. Association Lecture: Functional Aspects of Information Processing

- PART I: PREPARATORY PROCESSES AND MOTOR PROGRAMMING

- PART II: STIMULUS CLASSIFICATION AND IDENTIFICATION

- PART III: MEASUREMENT OF ATTENTION AND EFFORT

- PART IV: VISUAL INFORMATION PROCESSING

- PART V: LANGUAGE COMPREHENSION

- PART VI: SHORT-TERM MEMORY

- PART VII: SEMANTIC MEMORY

- PART VIII: REASONING, PROBLEM SOLVING, AND DECISION PROCESSES

- Author Index

- Subject Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Attention and Performance Viii by R. S. Nickerson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Cognitive Psychology & Cognition. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.