![]()

Keijiro Otsuka and Takashi Shiraishi*

1 Introduction

Why does a huge income gap still exist between developed and developing countries? How did Japan become the first advanced country outside the western world? Why has the economic performance of the Philippines and Indonesia been better compared with their higher-income neighbors, Malaysia and Thailand, in recent years? Why have South Asian countries, including India and Bangladesh, begun growing fast? On the surface, the income gap and different growth performance reflect the differences in technology, quality of human resources, and economic policies, but at the deeper level they reflect, in large measure, the success and failure of state building conducive to economic development. It is the contention of this volume that the issues raised above can be interpreted in a consistent manner within a broader analytical framework that subsumes the interactive processes between state building, contentious politics, and economic development.

A critical question is how a state conducive to development can be built. In this context, it is noteworthy that the case of Japan since the Meiji Restoration in 1868 is widely regarded as an example of successful state building and development (see for example Johnson 1982). Thus, it is certainly worth exploring the extent to which successful state building led to sustainable development, and asking the question “Which was more important during this interactive process?”: the evolution of an acceptable form of government (i.e. democratization), the ability of the state to implement effective and sustainable development policy, or the ability to reduce distributional conflicts that successful economic development may have generated between social groups, for Japan from a historical perspective. What becomes clear from the analyses in Chapters 2 and 3 in this volume is not only the importance of state building per se in promoting economic development but also the critical roles played by interactive processes among state building, economic development, and contentious politics in shaping the development paths that eventually — after the disastrous empire-building in the 1930s and first half of the 1940s — led to full democratization under occupational forces after World War II.

As with the case of Japan, a new state emerges out of internal conflicts, political reforms, or independence, and the first task that it must accomplish is to build new institutions. At this stage, the state is in many cases non-democratic, dominated by the elites, particularly landed elites and urban bourgeoisie representing the interests of the rich economic class. Without exception, new institutions lead to conflicts of interest of various sorts. Ethnic or class conflicts may, for example, arise when new institutions favor certain ethnic groups or certain economic classes at the expense of the majority of the people. Under such situations, economic development, if successful, is likely to lead to distributional inequity, which, in turn, may lead to contentious politics, social unrest, and repression. Such social and political instability, in turn, will depress incentives to make long-term investments, which are vital for long-term economic development.

In order to contain such conflicts, the dominant political group or the elites may decide to choose democracy, which is pro-majority, or even pro-poor, compared with non-democracy which is pro-elites. Or the state may adopt more equitable institutions and sustainable development strategies. Indeed, the term “developmental state,” which aims at economic development as a major purpose of politics, is commonly applied to relatively equitable development-oriented states in Asia, beginning with Japan, followed by the Newly Industrialized Countries of Singapore, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Korea, and later by ASEAN countries such as Malaysia, Thailand, and Indonesia. Furthermore, in lowincome countries, labor-intensive industries are often the only viable industries, and technology change may involve using more labor. Such development may be able to confer benefits to the majority of the population and thereby lessen the pressure on the state to democratize. On the other hand, economic dynamism increases the returns to human capital (Schultz 1975) and stimulates human capital accumulation (Otsuka et al. 2009). As a result, the importance of land as a factor of production decreases and landed elites tend to lose political influence. Instead, the educated middle-income class emerges as a new political force that may expedite democratization in favor of them or deter it as the social conflict between the rich and poor is defused. If democracy is created and consolidated, social and economic stability is likely to be established, thereby leading to sustainable economic development. Economic development, however, does not guarantee the endurance of democracy, as in the case of pre-war Japan (see Chapter 3).1 Thus, how state building, economic development, and contentious politics as well as democratization interact is a fundamental issue in development economics and political science.

Despite the close inter-dependence between state building, contentious politics, and economic development, there have been relatively few studies which squarely address the relationship between them.2 An exception is Why Nations Fail by Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson (2012). While their book primarily focuses on why there are so many extractive states, our volume explores the processes by which extractive states can be transformed into inclusive states, to use their terminology. Another book by the same authors (2006), Economic Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy, is very useful to understand the causes and processes of democratization, but the analysis of economic development and development policies is lacking. Other closely related books are Contention and Democracy in Europe, 1650–2000 and Democracy by Charles Tilly (2004, 2007), which analyze how contentious politics associated with state building lead to different degrees of democratization in different countries. Although we basically agree with both Acemoglu and Robinson’s and Tilly’s argument that democracy is born of contentious politics, we would like to point out that their books focus mainly on state building rather than the interactions between state building and economic development.

This volume attempts to synthesize diverse views on state building and economic development by critically reviewing the historical experience in Japan, exploring contemporary issues of state building and development in ASEAN and sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), and charting the success and failure of state policies for economic development in South Asia as well as SSA. By providing cutting-edge knowledge on state building and economic development based on a number of case studies, we hope to shed new light on this exceedingly difficult but important subject in the study of economic development.

The organization of this chapter is as follows. Section 2 presents the common analytical framework of this study, while Section 3 discusses how state building affects economic development by facilitating the long-term stability of the economy, and Section 4 explores the role of economic policies in economic development and state building. Section 5 provides an overview of the organization of the book.

2 Analytical framework

Following OECD (2008), state building may be defined as “an endogenous process to enhance capacity, institutions, and legitimacy of the state driven by state-society relations.” In our view, the state-society relations can be specified by the degree to which contentions among social forces or between the elites and social groups are contained or managed. “Institutions” refers to the political and economic institutions, including market and non-market institutions, property rights institutions, centralized and decentralized political institutions, and democratic and nondemocratic institutions, among others. Legitimacy is regarded as the acceptance of political authority by a population, whereas capacity pertains to administrative capacity in surveillance, maintenance of peace and order, taxation, allocation of budgets, and implementation of appropriate economic policies. Successful state building ensures political stability that leads to an economic environment conducive to long-term investments.

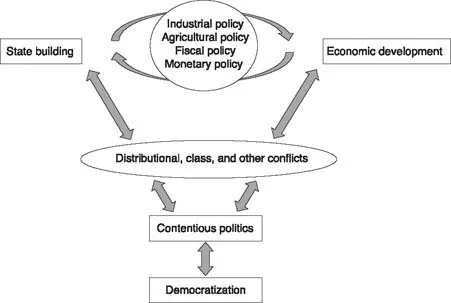

As shown in Figure 1.1,3 state building affects economic development because it is the state that provides public goods such as security and safety of people and property and implements industrial and agricultural development policies and macroeconomic policies. But state building is also shaped by development because development improves the legitimacy of the state and expands the tax base.

The two-way causal relationship between state building and economic development may also have negative results. Corruption, for example, adversely affects economic development and the legitimacy of the state in many cases as it reduces private returns to investment and distributes private benefits for policymakers (Shleifer and Vishny 1993). With or without corruption, however, both state building and economic development lead to changes in the distribution of economic benefits among ethnic groups, income classes, and the rural and urban population, changes that may trigger contentious politics and influence the course of democratization. In what follows, we sketch how state building, economic development, and contentious politics interact.

Figure 1.1 Analytical framework on the relationships among state building, economic development, and contentious politics

State building

State building in the developing countries is frequently affected by the land issue because land is a major asset in such countries and the majority of the population is engaged in farming. When land is abundant relative to labor, land does not command scarcity value and, hence, nobody has strong interest in the private ownership of land. However, because some cultivable land areas are uncultivated, such land is often claimed to be government land and later distributed to the politically influential class. Historically, this practice became one of the major sources of the inequitable ownership distribution of land and social injustice in poor countries (Lipton 2009). Historically, colonial governments consolidated large tracts of land and established large estates and haciendas. The landed elites thereby created often dominate not only in farming but also in commerce, industry, and politics, and oppose democratization that may lead to redistributive politics.

This is unfortunate not only politically but also economically because there are no scale advantages in farming in low-income countries where labor-intensive cultivation practices are adopted and monitoring hired workers in spatially dispersed and ecologically diverse conditions is costly (Hayami and Otsuka 1993). As a result, an inverse correlation is often observed between farm size and productivity, suggesting that small farms relying on family labor are more efficient than large farms relying on hired labor in both Asia and SSA (e.g. Holden et al. 2009, 2013; Larson et al. 2013; Lipton 2009).

As discussed above, almost without exception, large farms have been cr...