- 268 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

On Trotskyism (Routledge Library Editions: Political Science Volume 58)

About this book

Trotsky --brilliant publicist, enthusiastic speaker, organizer of the Red Army, eminent member of the Bolshevik Party during the first years of the Russian Revolution--has often been depicted as a romantic figure by biographers. Kostas Mavrakis does not see him in this light. Mavrakis submits Trotsky, his thought and work to a severe but fair critical examination. Among the issues reassessed by this controversial scholar are Trotsky's incapacity for concrete analysis, the 'economism' he shares with Stalin, his concepts of 'permanent revoluation' as compared with those of Lenin and Mao, his views and those of Stalin, on the Chinese Revolution, the fundamental traits of Trotskyism and of the different trotskyist organizations.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access On Trotskyism (Routledge Library Editions: Political Science Volume 58) by Kostas Mavrakis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Política y relaciones internacionales & Política. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

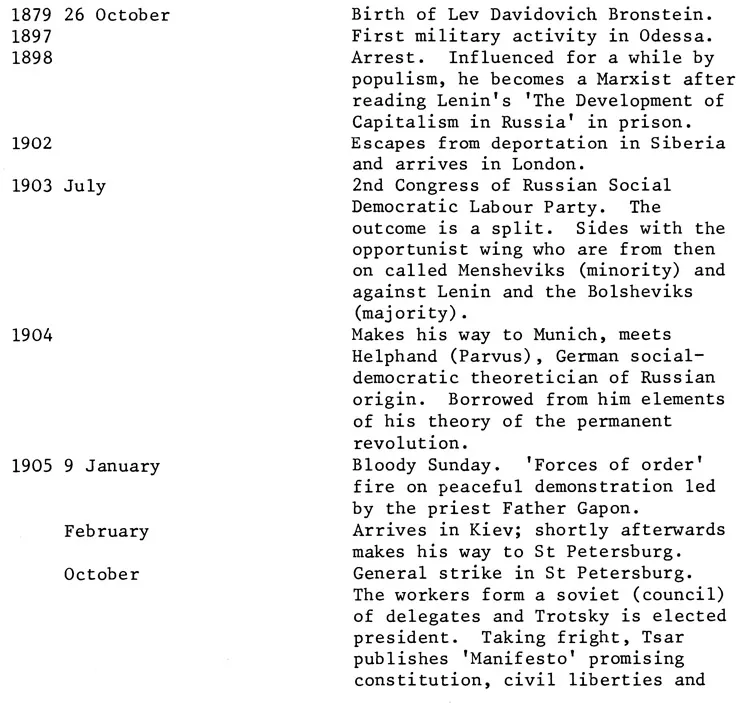

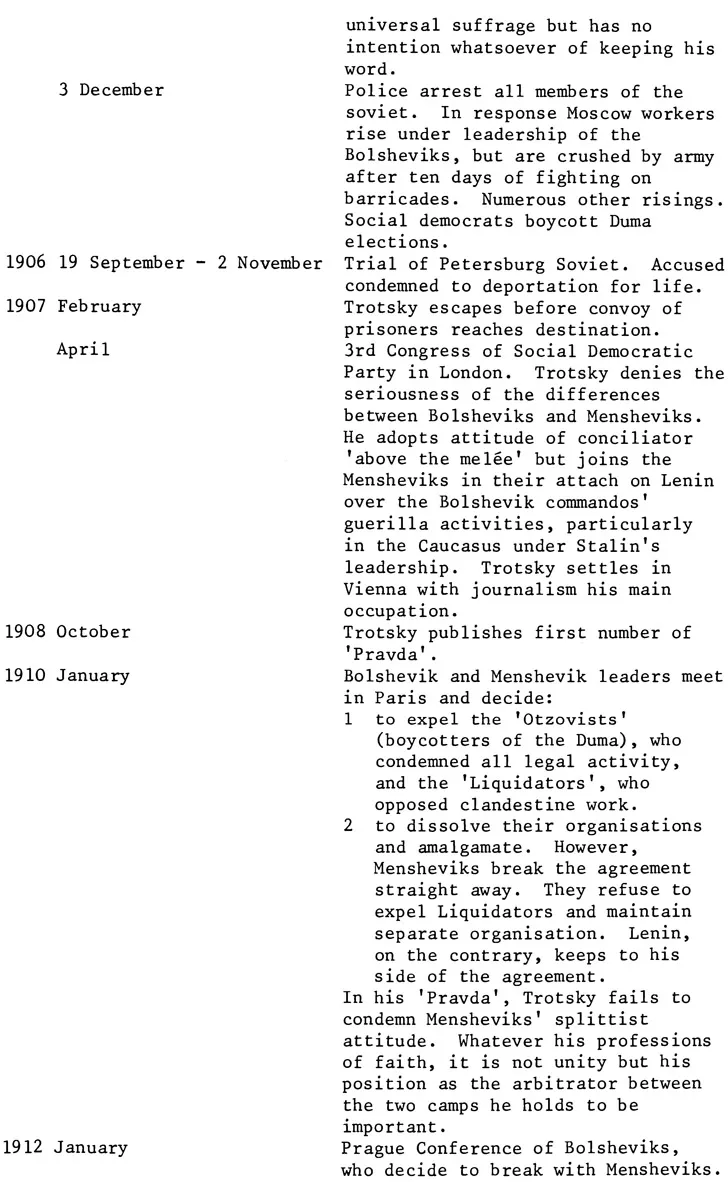

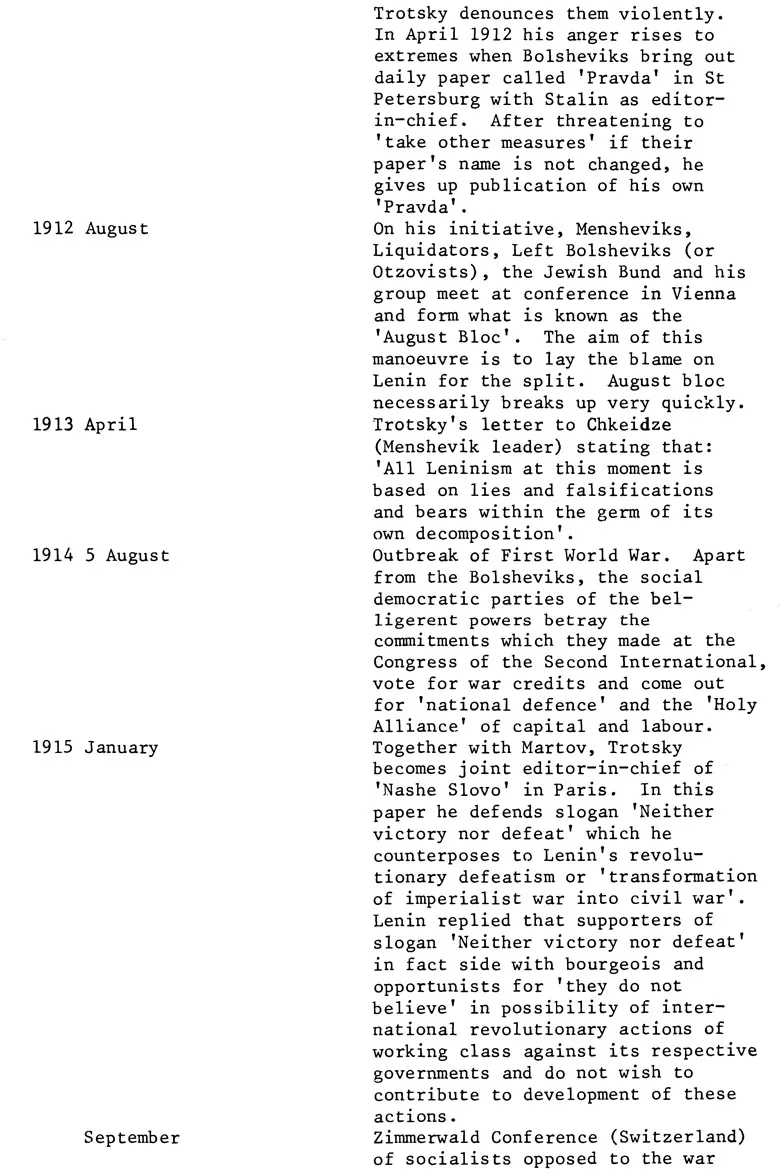

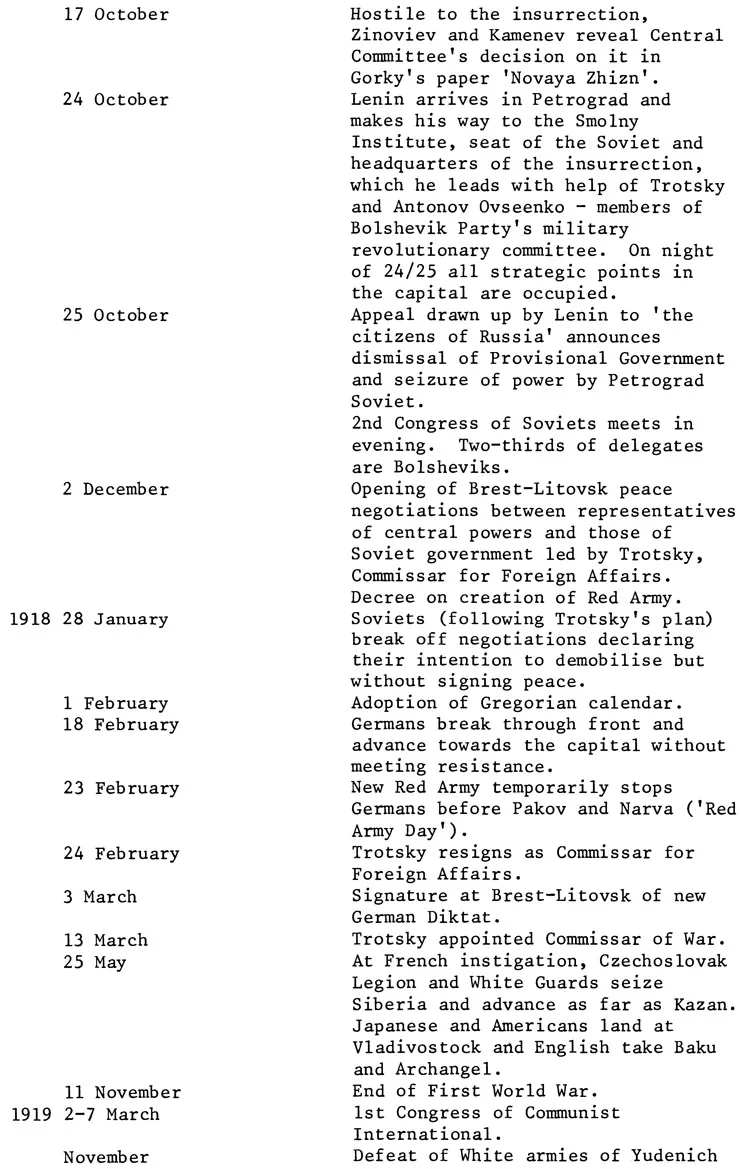

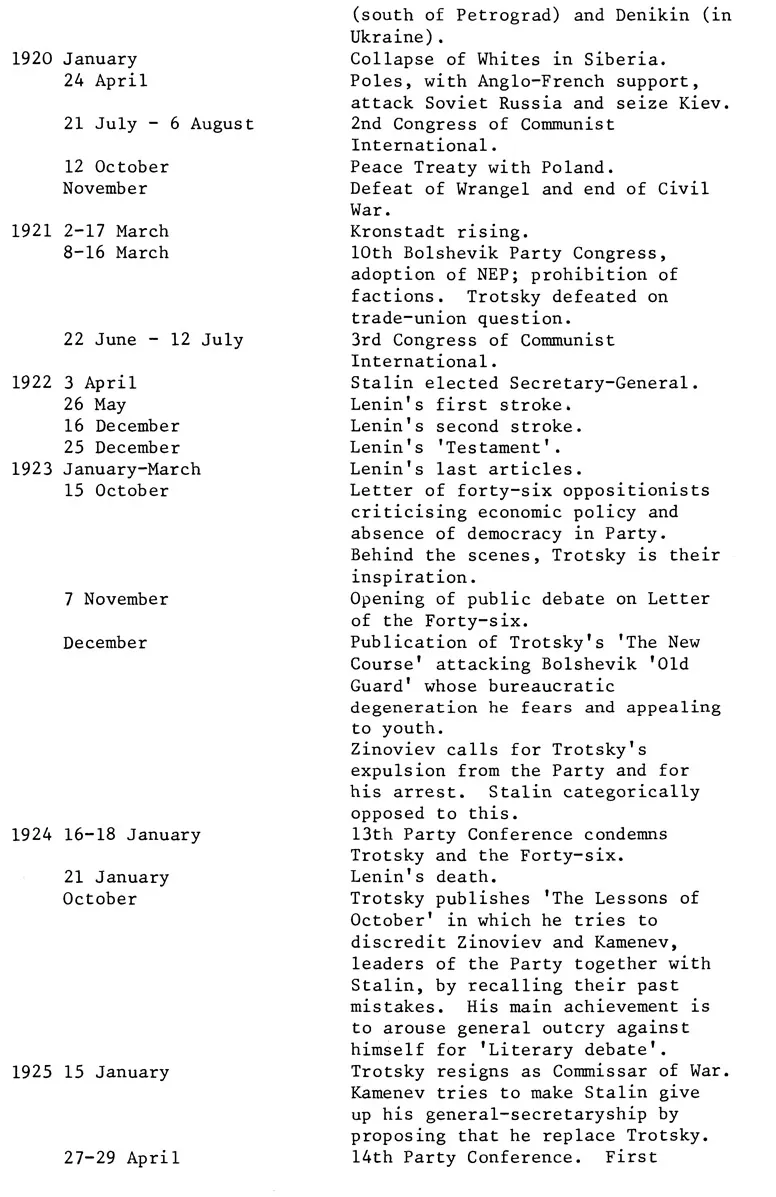

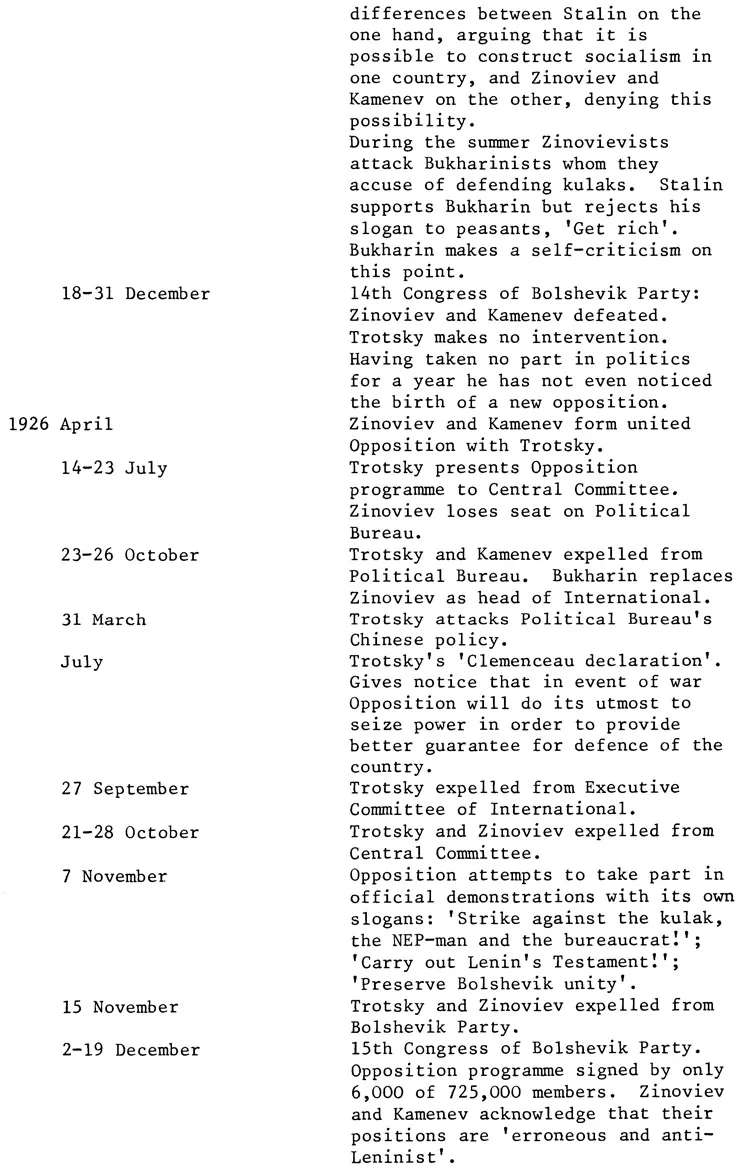

Biographical Landmarks

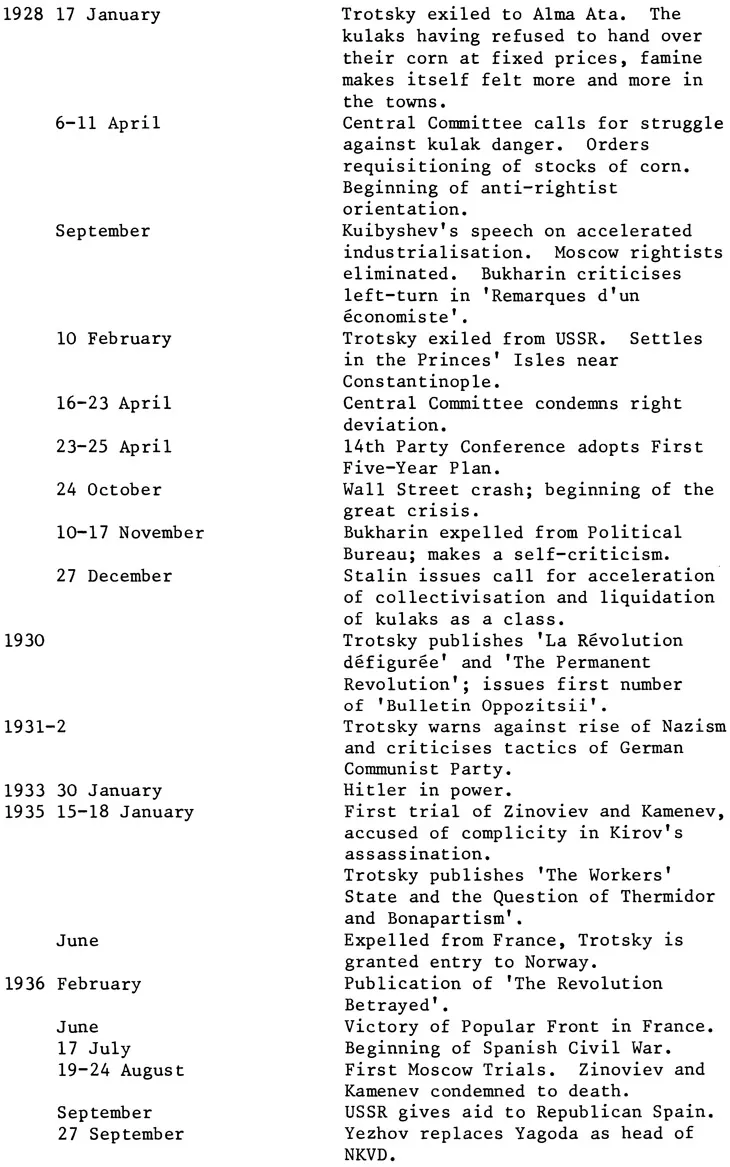

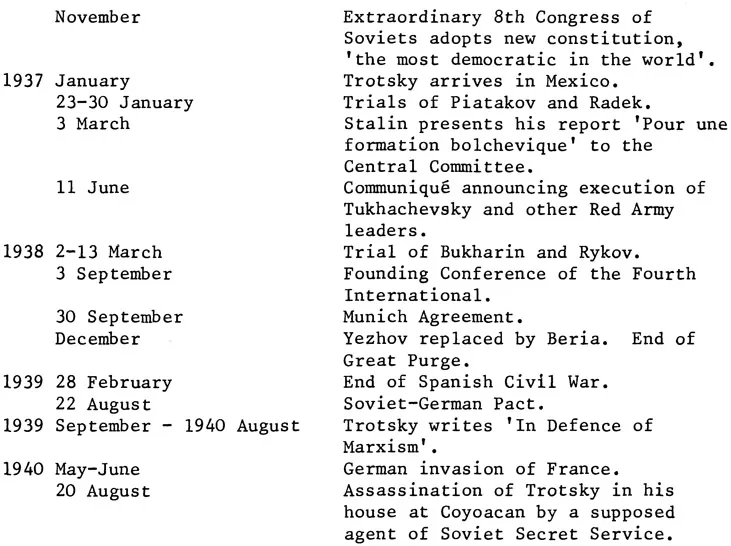

This chronology provides some details on certain points of Trotsky’s career which are not dealt with in the pages which follow and offers a framework to help in understanding them. Everything which is not absolutely necessary for this purpose has been omitted.

Chapter 2

An Atemporal Dogmatism

Trotsky’s ‘Original’ Theory

In May 1904 Trotsky had just been excluded from the editorial board of ‘Iskra’ at Plekhanov’s insistence. He continued, nevertheless, to collaborate with the Menshevik journal. At this time he made his way to Munich where he met the Russian social democrat, Alexander Helphand, whose nom de plume was Parvus. He was to remain with him until February 1905 and to fall strongly under his influence. Like him, while his sympathy went to the Mensheviks, he was to claim the role of arbiter, judge and pacifier of the two factions of the Russian Social Democratic Party, and in order to do this he was to keep himself apart from both sides. The ‘theory’ of the permanent revolution in its essential traits is due to Parvus. He was the first person to set out some of the ideas which continue to structure Trotskyist thought up to the present day.

In a series of articles entitled ‘War and revolution’ he argued that the national state, the birth of which corresponded to the needs of industrial capitalism, was henceforth superseded. The development of a world market shattered this compartmentalisation by accentuating the interdependence of nations.

At the beginning of the 1905 revolution Parvus wrote a preface to Trotsky’s book ‘Our Political Tasks’ in which he argued: ‘The Provisional Revolutionary Government of Russia will be a workers’ democratic government … As the Social Democratic Party is at the head of the revolutionary movement … this government will be social democratic … a coherent government with a social democratic majority.’

Trotsky was to conclude quite naturally that such a government could not but carry out a specifically social democratic policy and would therefore immediately commit itself to the road of socialist transformation. In this he was as much opposed to the Mensheviks who, arguing the bourgeois-democratic character of the revolution, supported the big liberal bourgeoisie who were seeking a compromise with Tsarism, as to the Bolsheviks who, while distinguishing the democratic stage from the socialist stage, considered that the proletariat had to mobilise the peasantry in order to take up the leadership of the democratic revolution and to carry out its tasks radically, which by no means implied that social democracy would be in a majority in a government set up after a victory of the people.(1)

At first sight it may seem that Trotsky’s theses are left-wing, those of Martov right-wing and those of Lenin centrist, but extremes converge and Martov agrees with Trotsky on more than one point. As we shall see further on, Lenin devoted an article to refuting the ideas of Trotsky which Martov had adopted on his own account.

Trotsky, the eloquent tribune, was accepted as the head of the Petrograd Soviet by the Mensheviks and the Bolsheviks precisely because he represented only himself and did not impede them in the pursuit of their policies. This was so true that, while both sides polemicised a great deal among themselves, afterwards they hardly ever bothered to refute his ideas.

Before going on to discuss the ‘permanent revolution’ in the basis of an analysis of the concrete situation in 1905, let us recall that Trotsky was not long to remain proud of having been Parvus’s disciple. The latter revealed himself a social chauvinist in 1914, and in addition an arms dealer and shady speculator. That is why Trotsky traced his theory back to Marx although he did not dare to deny his debt to Parvus.

It is true that Marx uses the term ‘permanent revolution’, particularly in ‘The Class Struggles in France’, but what he says about it is at such a level of generality that it cannot be relied upon to confer the palm of orthodoxy on Parvus and Trotsky, nor on Lenin and Mao. The former and the latter agree with Marx while differing among themselves. Besides, Marx was aware of the relatively general and abstract character of his definition of the permanent revolution since he apologises for not having the space to develop it. (2) It was only after 1905 that a differentiation occurs among those calling themselves Marxist over this concept. In any case, the reference to Marx is deceptive, for in the passages where the words ‘declaration of the permanent revolution’ appear, what is at issue is more reminiscent of the cultural revolution in China than the tactics advocated in 1905 by Trotsky. The latter explicitly invoked Lassalle, who had drawn from the events of 1848-9 the unshakable conviction that ‘no struggle in Europe can be successful unless, from the very start, it declares itself to be purely socialist’. (3) If Parvus is the father of Trotskyist theory, Lassalle is its grandfather. The notion of the permanent revolution peculiar to Parvus and Trotsky was an attempt to respond to the problems posed by the 1905 revolution. In what follows I shall endeavour to study the concrete situation at that time.

From Democratic to Socialist Revolution

(A summary of ‘Que faire?’, pp.16-24, UJC (M.L.) pamphlet no.3, Paris, 1967, translated as ‘What Is To Be Done?’)

In 1905 the imminent revolution had to accomplish bourgeois democratic tasks, that is, to sweep away the Tsarist state and its social basis - feudal property - which were holding back the development of capitalism. However, the bourgeoisie could not lead this revolution, given its alliance with the landowners and its infiltration into the state apparatus which it was gradually transforming from within. Hence the obvious paradox: the bourgeoisie had no interest in the bourgeois revolution; it inevitably preferred a compromise with Tsarism. In the countryside, however, the rural bourgeoisie, fettered as it was by feudal relations, had not developed freely. All the categories of peasants which were beginning to differentiate themselves still had a common interest in the overthrow of Tsarism.

The proletariat and the peasantry were thus the principal revolutionary forces at this time. An alliance between these two classes was necessary to overthrow Tsarism in a revolutionary way. The proletariat had to lead this alliance: it alone had the organisational ability which made its hegemony possible and necessary. For the proletariat to lead the revolution meant: to win over the peasantry, to rely on the revolutionary initiative of the peasant masses, to prevent the bourgeoisie from gaining the leadership of the peasant movement and defeating it by an incomplete and bureaucratic agrarian reform (decreed from above). The slogan of the revolutionary democratic dictatorship of the proletariat and the peasantry expressed this alliance and this hegemony. Furthermore, proletarian leadership, guaranteeing the consistency of the revolution (its radical character), would institute the conditions that would prepare the socialist revolution. This slogan made it possible for the Bolsheviks to participate in a provisional revolutionary government which would exercise this dictatorship. Which parties would be long-term members of this government? This was an abstract question in the following sense: only practice could resolve the question, only the real development of the revolution could provide the elements of an answer. This precise question lost its meaning after the defeat of the revolution and the appearance of a new alignment of class forces. The point is essential. The slogan ‘revolutionary democratic dictatorship of the proletariat and peasantry’ corresponded adequately to the objective situation of the 1905 revolution. It expressed with total accuracy the immediate tasks of the proletariat: the organisation of the peasants for the achievement of their joint dictatorship. It did not leave room for any ‘riddle’ (Trotsky). A slogan corresponds to the tasks of the moment. Like all slogans, the Bolshevik slogan in 1905 was an instrument of agitation and propaganda; it showed the workers the principal path that the revolution had to follow: the organisation of the peasants for the conquest of consistent democratic power; it oriented the proletarian revolution and freed the initiative of the peasantry. Trotsky, on the other hand, proposed to the proletariat that they should take over state power and afterwards make use of it to rouse the peasants: ‘Many sections of the working masses, particularly in the countryside, will be drawn into the revolution and become politically organised only after the advance-guard of the revolution, the urban proletariat, stands at the helm of the state.’ (4)

In 1917 the second revolution triumphed in the midst of imperialist war. The latter had accelerated social development. Capitalism had been transformed into state monopoly capitalism. In the countryside the process of differentiation had made headway. The Tsarist agrarian reform of Stolypin had strengthened the rural bourgeoisie. The war had united workers and peasants in uniform. It was mutinous soldiers who overthrew the Tsarist government. The revolution of February 1917 led to the installation of a dual power: on the one side, the provisional government representing the impe...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Original Title

- Original Copyright

- CONTENTS

- ABBREVIATIONS

- INTRODUCTION

- 1 BIOGRAPHICAL LANDMARKS

- 2 AN ATEMPORAL DOGMATISM

- 3 TROTSKY’S INCAPACITY FOR CONCRETE ANALYSIS

- 4 A BUREAUCRATIC ANTI-BUREAUCRATISM

- 5 REVISIONIST DEGENERATION OR CULTURAL REVOLUTION

- 6 STALIN AND TROTSKY ON THE CHINESE REVOLUTION

- 7 THE DEFEAT OF THE GREEK COMMUNISTS

- 8 CONCLUSION: THE FUNDAMENTAL TRAITS OF TROTSKYISM

- 9 CRITICAL NOTES ON SOME TROTSKYIST ORGANISATIONS

- APPENDICES

- NOTES

- BIBLIOGRAPHY