- 368 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Buddhist Suttas

About this book

This is a subset of F. Max Mullers great collection The Sacred Books of the East which includes translations of all the most important works of the seven non-Christian religions which have exercised a profound influence on the civilizations of the continent of Asia. The works have been translated by leading authorities in their field.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

MAHÂ-PARINIBBÂNA-SUTTANTA.

INTRODUCTION

TO THE

BOOK OF THE GREAT DECEASE

______________

IN translating this Sutta I have followed the text published by my friend the late Mr Childers, first in the Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, and afterwards separately. Inthe former the text appeared in two instalments, the first two sheets, with many various readings in the footnotes, in the volume for 1874; and the remainder, with much fewer various readings, ih the volume for 1876. The reprinted text omits most of the various readings in the first two sheets, and differs therefore slightly in the paging. The letters D, S, Y, and Z, mentioned in the notes, refer to MSS. sent to Mr. Childers from Ceylon by myself, Subhûti Unnânse, Yâtramulle Unnânse, and Mudliar de Zoysa respectively. The MS. mentioned as P (in the first two sheets quoted only in the separate edition) is, no doubt, the Dîgha Nikâya MS. of the Phayre collection in the India Office Library. The other four are now I believe in the British Museum.

______________

The Hon. George Tumour of the Ceylon Civil Service published an analysis of this work in the Journal of the Bengal Asiatic Society for 1839; but as he unfortunately skips, or only summarises, most of the difficult passages, his work, though a most valuable contribution for the time, now more than half a century ago, has net been of much service for the present purpose. Of much greater value was Buddhaghosa's commentary contained in the Sumangala Vilâsinî1; but the great fifth-century commentator wrote of course for Buddhists, and not for foreign scholars; and his edifying notes and long exegetical expansions of the text (quite in the style of Matthew Henry) often fail to throw light on the very points which are most interesting, and most doubtful, to European readers.

The Mâlâlankâta-vatthu, a late Pâli work by a Burmese author of the eighteenth century 1 is based, in that part of it relating to the last days of the Buddha, almost exclusively on the Book of the Great Decease, and on Buddhaghosa's commentary upon it Bishop fiigandet's translation into English of a Burmese translation of this work, well known under the title of ‘The Life or Legend of Gaudama the Budha of the Burmese,’ affords evidence therefore of the traditional explanations of the text. In the course either of the original author's recasting, or of the double translation, so many changes have taken place, that its evidence is frequently ambiguous and not always quite trustworthy: but with due caution, it may be used as a second commentary.

______________

The exact meaning which was originally intended by the title of the book is open to doubt Great-Decease-Book ' may as well mean ‘the Great Book of the Decease,’ as ‘the Book of the Great Decease’ This book is in fact longer than any other in the collection, and the epithet ‘Great’ is often opposed in titles to a ‘Short’ Sutta of (otherwise) the same name2. But the epithet is also frequently intended, without doubt, to qualify the immediately succeeding word in the title3; and, though the phrase ‘Great Decease,’ as applied to the death of the Buddha, has not been found elsewhere, it is, I think, meant to do so here 4.

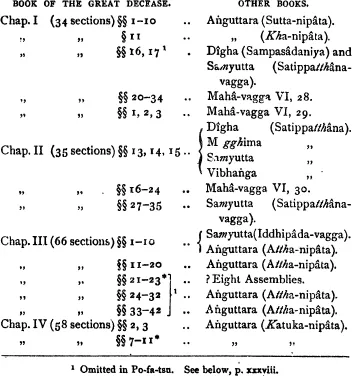

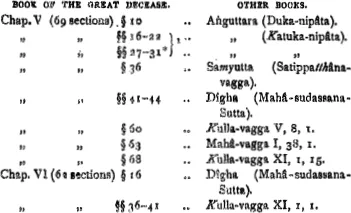

The division of the Book into chapters, or rather Portions for Recitation, is found in the MSS.; the division of these chapters into sections has been made by myself. It will be noticed that a very large number of the sections have already been traced, chiefly by Dr. Morris and myself, in various other parts of the Pâli Pitakas: whole paragraphs or episodes, quite independent of the repetitions and stock phrases above referred to, recurring in two or more places. The question then arises whether (1) the Book of the Great Decease is the borrower, whether (2) it is the original source, or whether (3) these passages were taken over, both into it, and into the other places where they recur, from earlier sources. It will readily be understood that, in the present state of our knowledge, or rather ignorance of the Pâli Pitakas, this question cannot as yet be answered with any certainty. But a few observations may even now be made.

Generally speaking the third of the above possible explanations is not only more probable in itself, but is confirmed by parallel instances in literatures developed under similar conditions, both in the valley of the Ganges and in the basin of the Mediterranean.

It is quite possible that while some books—such as the Mahâ-vagga, the Kulla-vagga, and the Dîgha Nikâya—usually owe tneir resemblances to older sources now lost or absorbed; others—such as the Samyutta and the Aṅguttara—are always in such cases simply borrowers from sources still existing.

At the time when our Book of the Great Decease was put into its present shape, and still more so when a Book of the Great Decease was first drawn up, there may well have been some reliable tradition as to the events that took place, and as to the subjects of his various discourses, on the Buddha's last journey. He had then been a public Teacher for forty-five years; and his system of doctrine, which is really, on the whole, a very simple one, had already been long ago elaborated, and applied in numerous discourses to almost every conceivable variety of circumstances. What he then said would most naturally be, as it is represented to have been, a final recapitulation of the most important and characteristic tenets of his religion. But these are, of course, precisely those subjects which are most fully and most frequently dealt with in other parts of the Pâli Pitakas. No record of his actual words could have been preserved. It is quite evident that the speeches placed in the Teacher's mouth, though formulated in the first person, in direct narrative, are only intended to be summaries, and very short summaries, of what was said on these occasions. Now if corresponding summaries of his previous teaching had been handed down in the Order, and were in constant use among them, at the time when the Book of the Great Decease was put together, it would be a safe and easy method to insert such previously existing summaries in the historical account as having been spoken at the places where the Teacher was traditionally believed to have spoken on the corresponding doctrines. In the historical book the simple summaries would sufficiently answer every purpose; but when each particular matter became the subject of a separate book or division of a book, the same summaries would be included, but would be amplified and elucidated. And this is in fact the relation In which several of the recurring passages, as found in the Book of the Great Decease, stand to the same passages when found elsewhere.

On the other hand, some of the recurring passages do not consist of such summaries, but are actual episodes in the history. As an instance of these we may take the long extract at the end of the first, and the beginning of the second chapter (I, 20–II, 3, and again II, 16–II, 24), which is found also in the Mahâ-vagga. The words are (nearly1) identical in both places, but in the Book of the Great Decease the account occurs in its proper place in the middle of a connected narrative, whereas in the Mahâ-vagga, a treatise on the Rules and Regulations of the Order, it seems strangely out of place. So the passage, also a long one, with which the Book of the Great Decease commences (on the Seven Conditions of Welfare), seems to have been actually borrowed by the Anguttara Nikâya from our work.

The question of these summaries and parallel passages cannot be adequately treated by a discussion of the instances found in any one particular book. It must be considered as a whole, and quite apart from the allied question of the ‘stock phrases’ above alluded to, in a discussion of all the instances that can be found in the Pâli Pitakas. For this purpose tabulated statements are essential, and as a mere beginning such a statement is; here annexed (including the passages, marked with an asterisk, which have every appearance of belonging to the same category).

______________

No Sanskrit work has yet been discovered giving an account of the last days of Gotama; but there are several Chinese works which seem to be related to ours. Of one especially, named the Fo Pan-ni-pan King (apparently Buddha-Parinibbâna-Sutta, but such an expression is unknown in Pâli), Mr. Beal says 2:

‘This appears to be the same as the Sûtra known in the South…. Is was translated into Chinese by a Shaman called Fa-tsu, of the Western Tsin dynasty, circa 200 A.D.’

I do not understand this date. The Western Tsin dynasty is placed by Mr. Beal himself on the fly-leaf of the Catalogue at 265–313 A.D. And whether the book referred to is really the same work as the Book of the Great Decease seems to me to be very doubtful. At p. 160 of his ‘Catena of Buddhist Scriptures from the Chinese’ Mr. Beal says, that another Chinese work ‘known as the Mahâ Parinirvâna Sûtra’ ‘is evidently the same as the Mahâ Parinibbâna Sutta of Ceylon,’ but it is quite evident from the extracts which he gives that it is an entirely different and much later work.

On this book there would seem further to be a translated commentary, Ta Pan-ni-pan King Lo, mentioned at p. 100 of the same Catalogue, and there assigned to Chang-an of the Tsin djnasty (589–619 A.D.).

At pp. 12–13 of the same Catalogue we find no less than seven other works, and an eighth on p. 77, not indeed identified with the Book of the Great Decease, but bearing titles which Mr. Beal represents in Sanskrit as Mahâparinirvâna Sûtra. They purport to be translated respectively—

| A.D. | ||

| 1. | By Dharmaraksha of the Northern Liang dynasty | 502–555 |

| 2. | By Dharmaraksha of the Northern Liang dynasty | |

| 3. | By Fa Hian and Buddhabhadra of the Eastern Tsin dynasty | 317–419 |

| 4. | By Gñâbhadra and others of the ... |

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- General Introduction to the Buddhist Suttas

- 1. The Book of the Great Decease (Mahā-Parinibbāna Suttanta)

- 2. The Foundation op the Kingdom of Righteousness (Dhamma-Kakka-ppavattana Sutta)

- 3. On Knowledge of the Vedas (Tevigga Suttanta)

- 4. If He Should Desire (Ākankheyya Sutta)

- 5. Barrenness and Bondage (Ketokhila Sutta)

- 6. Legend of the Great King of Glory (Mahā-Sudassana Suttanta)

- 7. All The Āsavas (Sabbāsava Sutta)

- Index

- Transliteration of Oriental Alphabets adopted for the Translations of the Sacred Books of the East

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Buddhist Suttas by F. Max Muller, T.W. Rhys Davids in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Ethnic Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.