![]()

Part I

The sandbox of the city

![]()

Chapter 1

The city as instructor

Pedagogical avant-garde and urban literacy in Germany around World War I

Håkan Forsell

Introduction

In the modern era, at least since the Enlightenment, features of social anarchism can be observed in recurrent attempts to challenge the school curriculum and the educational upbringing of children. From Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi to Paulo Freire, one can follow a pedagogical tradition that confronts conventional instructions, state directives and a book learning remote from real life, in order to have children master their own environment and social relationships. Colin Ward belonged to this tradition. His ideas about environmental education found resonance in the 1960s and 1970s in overlapping movements that aimed to rethink and re-evaluate the modern city as a living environment for children. In The Child in the City (1978), Ward aimed at the integration of children in the urban environment, in order to get them out of the artificial containment of the school and into society as fully recognised and active citizens. He recalled previous scattered witnesses from the twentieth century to illustrate how:

[the] city is in itself an environmental education, and can be used to provide one, whether we are thinking of learning through the city, learning about the city, learning to use the city, or to control or change the city.

(1978: 176)

The sense of urban crisis in Western Europe during the 1960s and 1970s had, of course, strong economic and social origins. But the debate was also influenced by a notion that it would be possible to restore, or re-establish, connections between social life, knowledge, skills and the urban environment of a sort that were believed to have co-existed previously, before urban planning, car traffic, sprawling suburbs and residential segregation.

Contemporary social debates indicated that children in cities had once had access to their own local sphere, like a habitat, a social and cognitive completeness; an enclosed treasure box full of valuable relations and knowledge. The American educational historian Daniel Calhoun wrote in 1969 that post-war urban planning had actually crushed a system of cognitive exchange that used to be a power source for the social and economic modernisation of Western European cities: “The city has been intruding into the learning process as a kind of Automatic Teaching Environment – poorly and chaotically programmed, but effective for all that…” (1969: 312).

This preoccupation with the relationship between social knowledge, educational institutions, and the urban environment had in fact materialised earlier. The decades surrounding World War I were formative of a new attitude towards social and educational ideals in relation to urbanised culture. In this chapter, I will turn my attention to an educational reform movement in predominantly German-speaking cities at the beginning of the twentieth century and discuss aspects of urban environmental education that cast a persuasive historical perspective on the work of Colin Ward.

Großstadtpädagogik – The child as a pupil in the city

During the mature phase of industrialisation and urbanisation in Western Europe around 1900, reform-oriented and progressive teachers and intellectuals did not usually trust the society that existed immediately at hand. From their perspective, the modern urban environment did not provide the most suitable context, reference and resonance for the work of the school. John Dewey had in The School and Society (1900) reacted against this intellectual distrust of the industrial society and given teachers in the cities the task of restoring the values that lay behind the factory buildings and industrial complexes, the values upheld by social ties, of families and neighbourhoods. He argued that the principal problem of education was how to adjust the child to life in the city. How should the school integrate the advantages of modern society and at the same time offer other aspects of life, such as personal responsibility, occupational pride and both tactile and intellectual knowledge of the necessities of existence? According to Dewey, the contemporary disconnection between school and society was not the result of some kind of degeneration of society’s vital functions due to economic development, nor of a sudden widespread ignorance of that which still constituted the great moral issues – honesty, thrift, community. Rather, it was caused by “an inability to appreciate the social environment that we live in today” (Dewey 1972/1903: 21ff).

The impact of Dewey’s pedagogical thinking on the general reform movement became increasingly strong during the era of the Weimar Republic (1919–1933). But around 1900, his social-cognitive approach to learning was in certain aspects problematic for other approaches to instruction and upbringing in German society. The notion that the child needed a “private inner space” was essential to hegemonic, bourgeois educational thought and praxis, and corresponded to a strong spatial individualisation of the lived environment (Wietschorke 2008: 210). The conviction that the process of learning depended on a dynamic relation between the child and the child’s immediate environment was also difficult to reconcile with one of the most startling writings of the time, Ellen Key’s The Century of the Child (in German translation in 1902), which advocated a child-centred approach to education and parenting that would free the children from external constraints, enabling them to develop their own inner abilities.

However, there were exceptions. During the 1910s and 1920s, the concept of Großstadtpädagogik (metropolitan pedagogy) found a foothold in educational practice and schooling debates in larger urban areas in Germany and Austria. The advocates of this loosely organised reform movement – predominantly progressive, socially liberal primary school teachers in rapidly growing cities like Berlin, Bremen, Hamburg and Vienna – emphasised urban space as a learning environment of the utmost importance. They experimented with excursions, object lessons and new textbooks to “adjust” the official school curriculum to real-life situations and demands. They also sought to put into practice the conviction that the city could serve as a vehicle for democratic culture based on secular, non-confessional teaching and community awareness. The teachers wanted pedagogical practice to overcome the phobia of the big city. Urban children lived in environments of learning that needed recognition. And for the educational reform movement this consideration should not be seen as a limitation (Fuchs 1906: 3ff; Tews 1911: 2).

The holistic approach of the metropolitan educators included elementary skills, which could be seen in the efforts made in textbook production and in the didactic renewal of ABC books for the youngest pupils. The pedagogical efforts of metropolitan instructors embedded the subjects taught, and especially reading and writing exercises, in a recognisable and meaningful context – the urban environment as the child’s home environment. The ambition went beyond the purely technical skills of reading and writing: literacy conceptualised the possibilities of independence and communication and thereby created an ability on the part of the individual child to find a meaningful position in relation to society’s increasing demands for rationality, specialisation and autonomy.

Fritz Gansberg, a primary school teacher in Bremen, was one of the leading figures in this opposition to traditional schooling. The explicit purpose of his 1904 textbook, Streifzüge durch die Welt der Großstadtkinder, was to conquer a new thematic field for lesson content, namely the field of urban culture. According to Gansberg, “… the urban child did not have every-day experiences of nature, and since nature was not alive, then neither could the words of the teacher come alive.” (Gansberg 1904: 1ff). Gansberg’s programme became the point of departure for other instructors who wanted to integrate attention to the urban environment in already established approaches to teaching, which had taken pupils outside the school gates, into rural settings. Prior to 1914, a series of alternative textbooks were produced comprising lists of vocabulary, simple descriptions of recent innovations and infrastructure, with overviews of the urban landscape. Instead of the common static visualisation on large boards in the classroom, direct interaction with the surrounding environment was emphasised through excursions and projects. The city itself was used as an “object lesson”.

One other early proponent of the method, the Leipzig primary school teacher Arno Fuchs, recommended in a textbook that object teaching through the city should start with some kind of a creative overview. This was represented by an imagined balloon trip over the cityscape, described in a lively way by his textbook, the idea of which was that, guided by the teacher, the pupils should become acquainted with the details and important connections and dependencies in the real city. The city offered a multitude of concrete examples of innovations that, according to Fuchs, could be used for schooling. For example, in natural sciences the steam engine, electricity, the telegraph and magnetism could demonstrate everything which provided for and supported urban society in its progress. The only “pedagogical” approach that Fuchs expressly discouraged was to take the subway/underground with school children. The experience had no didactic advantages, he wrote, when the understanding of the environment was fragmented and did not provide a holistic experience (Fuchs 1906: 3, 17).

History was likewise relocated in an urban context. Local history had been dismissed by other reformists for its tendency to introduce fantastic elements and romanticism into teaching. For metropolitan pedagogy, however, history had a place – not as a means of exploring a distant past, but rather as a means of introducing the kinds of knowledge and competence required by contemporary demands. Consequently, local history in the city was considered urban science, since the modern city had become the place of origin for generations of citizens.

In this chapter I intend to study and analyse three major fields of interaction that urban educators found especially important from the point of view of working towards a new knowledge relationship between the child and the environment: first, the child’s encounter with the written word; second, the child’s contact with city streets; and third, the development of play as an essential learning practice in the child’s home environment.

The textbooks of urban literacy

The textbooks produced by the metropolitan educators aimed to change educational practice. They took an interest in teaching methods as cultural techniques that depended on social and environmental context. The Fibel, the traditional German primer, was the main vehicle for teaching literacy. The Fibel had a double function: it was a tool for the alphabetisation process as well as instrument for socialisation. Hence, the primer combined instruction with representation. Simple illustrations conveyed social values and ways of categorising the world and were integrated into an overall didactical concept.

During their early years at school, pupils were set an assignment to compose their own Fibel, using everyday observations and descriptions of occurrences and “snapshots” of their lives. In this, it was important that the reality was not overshadowed by the act of writing. Gansberg and other metropolitan educators considered writing to be primarily a social activity. To imitate famous writers or to adapt a literary style was completely wrong and in the metropolitan textbooks, fairytales and fantasy had no place. Instead, the idea was that the child should learn to create connections and understand causes out of the unattached, sweeping urban gaze: “… contemporary circumstances promote a type of character than can appraise situations and respond quickly and the teacher must therefore enhance independence – since we demand it from our children.” (Silex 1910: 2, 6). The child’s natural inclination to “observe” the surroundings had to be treated as an essential part of knowledge formation in urban schools. It was a necessary gathering of “raw material” for the experience of the child.

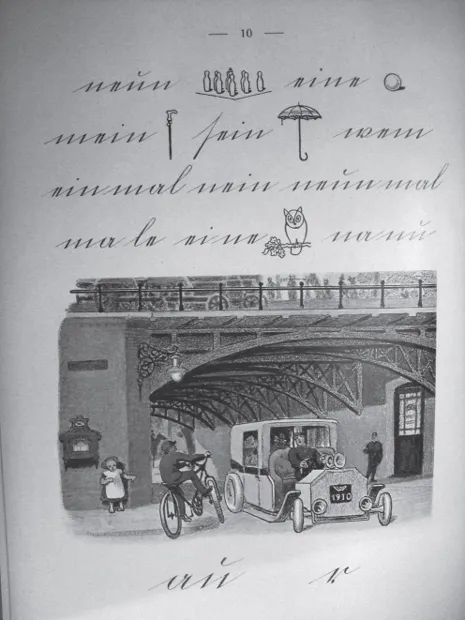

Figure 1.1 Illustration and reading exercise from ABC – Neue Fibel für Stadtkinder (1914).

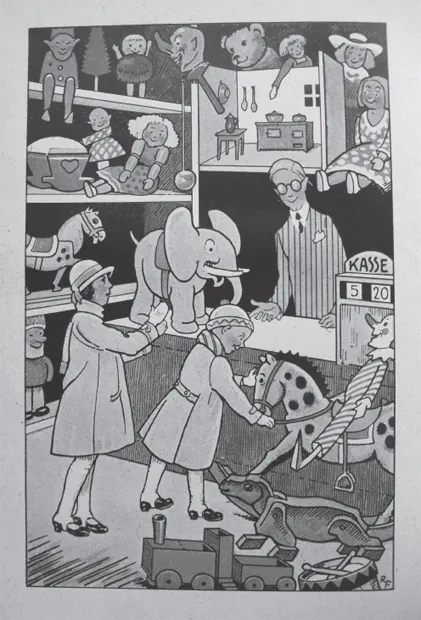

Figure 1.2 Berliner Fibel, special edition for Groß-Berlin (1926).

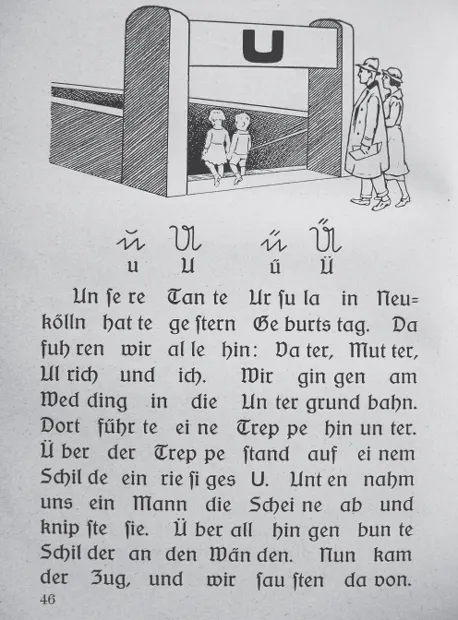

Figure 1.3 Berliner Fibel, special edition for Groß-Berlin (1926).

The instruction in literacy and language that the progressive urban reformists undertook aimed at developing a “storyography” for city children, dealing with “places worth telling about”; places children knew of but were not occupied or captured by school institutions or the textual world of school and its didactic arrangements (Gleim 1985: 249). The metropolis was a workshop for essay-writing – a world of new objects, spaces and relationships – all of which had to be given names. Thus, it was made possible for children to “claim” their local environme...