![]()

1 Peak oil, climate change, and China

Capitalism is a historically unique system driven by the pursuit of endless economic growth. In a modern capitalist society, periods of rapid economic growth are associated with expanding employment, rising living standards, declining social conflicts, and stable political systems. Periods of economic stagnation or decline are characterized by shrinking employment, falling living standards, growing social conflicts, and political instability. In the long run, capitalism cannot function and reproduce itself without growth. But can economic growth be sustained indefinitely? In fact, can humanity survive the consequences of infinite economic growth?

Modern economic growth, or systematic economic growth that brings about fundamental transformation to people’s conditions of life in every one or two generations, was unknown to humanity until about two centuries ago. According to Angus Maddison (2010), who compiled the world’s most authoritative data on historical economic statistics, world population grew slowly, from 230 million to 270 million, from ad 1 to 1000 (an increase of 40 million over 1,000 years). World population increased to 440 million by 1500 (an increase of 170 million over 500 years), to 1,040 million by 1820 (an increase of 600 million over 320 years), and to 6.1 billion by 2000 (an increase of five billion over 180 years). World economic output barely changed from ad 1 to 1000. It doubled from 1000 to 1500, tripled from 1500 to 1820, and increased by more than 50 times from 1820 to 2000.

The rapid expansion of world population and economic output over the past two centuries has been made possible by the massive growth of fossil fuel consumption. Without coal, there would have been no industrial revolution. Coal, oil, and natural gas have made possible the successive technological revolutions that have taken place since the nineteenth century.

But fossil fuels are nonrenewable resources and will eventually be depleted. Alternative energy resources exist in the form of nuclear and renewable energies (such as wind, solar, and biomass). But can the alternative energies replace fossil fuels on a sufficiently large scale to sustain the current and future global material consumption? Can the alternative energies keep expanding to sustain an ever-growing global economy? What are the economic and technological obstacles? Are the “renewable energies” also subject to the limits of resources and ecological constraints?

The consumption of fossil fuels results in the emission of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases. The accumulation of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere has led to rising global temperatures and threatens to bring about unprecedented ecological catastrophes. The survival of the global ecological system and the future of human civilization are at stake.

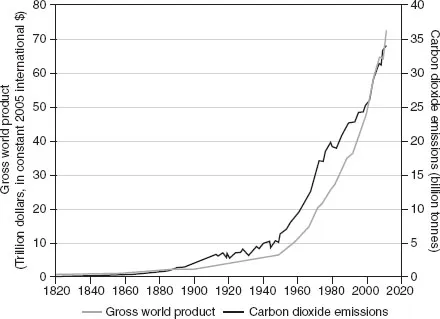

Climate stabilization, in a manner that is consistent with the preservation of civilization as we know it, requires drastic reductions of carbon dioxide emissions. However, historically, world economic growth has been closely linked to fossil fuel consumption and carbon dioxide emissions. Figure 1.1 shows the historical relationship between the world economic output and carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuels burning from 1820 to 2012. Since 1820, world carbon dioxide emissions have increased by about 700 times.

Is it conceivable that, as the world economic output continues to skyrocket toward infinity, world carbon dioxide emissions would nevertheless manage a sharp U-turn, starting to decline soon and declining rapidly in the coming decades? Or will the required reductions of carbon dioxide emissions and fossil fuel consumption necessitate the end of economic growth, if not absolute contraction of the global economy?

The answers to these questions to a large extent depend on what will happen to China in the coming decades. In Figure 1.1, the growth of world carbon dioxide emissions accelerated in the early twenty-first century. The acceleration was due largely to China’s rapid industrialization and the rise of China as a global economic power. It is safe to say that, without a fundamental decarbonization of the Chinese economy, there will be virtually no chance for humanity to achieve reasonable climate stabilization—that is, climate stabilization consistent with the preservation of civilization.

However, a decarbonization of the Chinese economy is likely to require not only major technical changes but also fundamental social and political transformations. This book contends that the requirements of climate stabilization and energy sustainability will impose insurmountable limits on both Chinese and global economic growth. Sooner or later, both China and the world will have to adapt to a steady-state economy or an economy consistent with zero economic growth. This book further argues that the current capitalist system is fundamentally incompatible with an economy based on zero economic growth. In this sense, an alternative social system is not only possible but also inevitable, were human civilization to survive the demise of capitalism.

Figure 1.1 World economic output and carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuels burning (1820–2012) (sources: Gross world product in constant 1990 international dollars from 1820 to 1980 is from Maddison (2010), converted to gross world product in constant 2005 international dollars by the author. Gross world product in constant 2005 international dollars from 1980 to 2011 is from the World Bank (2013), updated to 2012 using world economic growth rates from International Monetary Fund’s World Economic Outlook (IMF 2013). Carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuels burning from 1820 to 1965 are from EPI (2012a). Carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuels burning from 1965 to 2012 are from BP (2013)).

Capitalism and accumulation of capital

Immanuel Wallerstein, the leading world system theorist, defined capitalism as a historical system based on “the endless accumulation of capital” (Wallerstein 1974). Among many different definitions of capitalism, this is probably the one that best captures the essential difference between capitalism and the previous historical systems.

For any human society to function and develop, material production has to take place. Natural resources have to be exploited and transformed by human labor into useful goods and services to meet certain human needs and desires. A society’s total product is the total amount of goods and services produced over a certain period of time. Out of a society’s total product, a portion has to be committed to the replacement of various means of production (such as raw materials, tools, and machines) used up during the production. Another portion has to be committed to the population’s basic needs (what constitutes people’s basic needs may vary depending on historical and societal conditions). If, after subtracting what is required to replace the means of production used up and to meet the population’s basic needs, there are still some goods and services left, then the remaining part of the total product is known as the “surplus product.” A society’s basic character, to a large extent, depends on how the surplus product is produced, appropriated, and used.

Table 1.1 illustrates the relationship between a society’s total product and its components.

For much of early human history, the levels of material production were barely sufficient to meet the population’s subsistence. There was little or no surplus product. With the rise of agriculture, a sizeable surplus product began to be produced and early civilizations emerged in different parts of the world between 10,000 and 7,000 years ago.

Since the beginning of civilization, various human societies have been divided into different and often antagonistic social classes. In various pre-capitalist societies, the great majority of the population (such as peasants and slaves) did the basic productive work, producing the society’s total product, but only received a portion that was barely sufficient for their subsistence. The surplus product was concentrated in the hands of a small group of elites (such as kings, aristocrats, feudal lords, and slave owners). It was used for the elites’ luxury consumption, certain public functions (such as maintaining agricultural infrastructure and storage), and a variety of wasteful activities (such as military conquests and the building of imperial tombs).

Table 1.1 A society’s surplus product and total product

Society’s Total Product |

Surplus Product |

Population’s Basic Needs |

Replacement of Means of Production Used Up |

In the pre-capitalist societies, the ruling elites were primarily interested in the “use values” of the surplus product. That is, they were principally concerned with the physical usefulness of the surplus product in order to meet certain needs or desires directly. Money existed and, in some societies, monetary transactions were quite substantial (such as in the Roman Empire, the Arabic Empire, the Ottoman Empire, and China’s Song Dynasty and Ming Dynasty). But, by and large, money and market relations did not dominate the pre-capitalist economies.

Because the pre-capitalist ruling elites were primarily interested in the surplus product’s direct physical usefulness, the surplus product was almost entirely consumed. There was little left to be used for the expansion of production capacity or technological innovation. As a result, both the population and the economic output grew very slowly, if they grew at all.

Under capitalism, virtually all economic and social activities are dominated by market relations. Every good or service can be turned into a “commodity” or can be measured by a certain monetary value. The surplus product has been transformed into “surplus value.” Unlike the pre-capitalist elites, the capitalists are primarily interested not in the surplus product’s use values, but in the surplus value, more commonly known as “profit.”

With the dominance of market relations, every capitalist has to engage in constant and intense competition against one another. Those who fail in competition will be bankrupt and cease to be capitalists. To prevail in the competition, every capitalist is compelled to use a large portion of his or her profit to make new investment—that is, to “accumulate capital”—in order to survive as a capitalist and to gain advantages against actual or potential competitors. Accumulation of capital leads to the expansion of production and the development of new technologies. As the capitalist economic relations become dominant, capital accumulation and economic growth become more or less self-sustained. Both the population and economic output start to “take off” and grow exponentially.

Thus, unlike the pre-capitalist societies, modern capitalism is inherently built to pursue economic growth on increasingly larger scales. As there is no inherent limit to the amount of monetary wealth any capitalist desires to have, and market competition compels all capitalists to accumulate increasingly larger amounts of capital, there is no limit to economic growth from within the system. In this sense, the capitalist system may be characterized as one that is based on the “endless accumulation of capital” or the pursuit of infinite economic growth.

But can economic growth really be infinite? Is infinite growth possible in a physically limited planet? This was the question raised by Meadows et al. (1972) in their classical book on The Limits to Growth.

The limits to growth

In the 1972 book, Meadows et al. used computer modeling to demonstrate that unlimited, exponential economic growth would eventually deplete the earth’s resources and cause runaway ecological damages, eventually leading to economic and societal collapse.

In a recent study, Turner (2008) studied the historical data for world population, industrial production, services production, remaining non-renewable resources, and pollution from 1970 to 2000. Interestingly, Turner found that the observed data agreed well with the original “standard run” scenario presented in The Limits to Growth, a scenario which predicted global collapse by the mid-twenty-first century.

In June 2012, Nature magazine, one of the world’s leading science journals, published a paper co-authored by 22 scientists. The scientists argued that, due to over-consumption, population growth, and environmental destruction, the earth is rapidly approaching a global tipping point beyond which the biosphere could experience swift and irreversible change, with catastrophic consequences for humanity and other species (Barnosky et al. 2012).

These studies raise important and urgent questions. Is the existing world system of capitalism compatible with the basic requirements of ecological sustainability and the long-term survival of human civilization? If not, can the system be reformed to meet these requirements? If not, can the system be replaced by a fundamentally different system? What will be the basic character of the new system? How long will it take for the systemic transition to take place? Does humanity still have time?

Peak oil: the beginning of the end?

How humanity responds to the current global crisis may determine the fate of the global ecological system and human civilization for centuries to come. But in the near future, it is the impending peak of world oil production that may impose the single greatest constraint on global economic growth.

Oil, or petroleum, is a naturally occurring flammable liquid consisting of hydrocarbons (a hydrocarbon is an organic compound consisting of hydrogen and carbon). It derived from ancient fossilized organic materials (such as zooplankton and algae). As many layers of the organic materials’ remains settled to sea or lake bottoms, they were buried under sedimentary rock and underwent intense heat and pressure. If the temperature was high enough, the organic matter would be transformed into liquid or gaseous hydrocarbons, which became, respectively, oil or natural gas.

Most of the oil found today was formed during two geological eras: the Jurassic period of 169–144 million years ago and the Cretaceous period of 119–89 million years ago (Aleklett 2012: 25). Oil is in effect stored solar energy (the energy embodied in the organic matter derived from solar energy) that had taken millions of years to be formed and accumulated. However, over the past one and a half centuries, humanity has already extracted and consumed 170 billion tonnes of oil. By the mid-twenty-first century, the world will likely have consumed more than half of the ultimately recoverable oil resources.

Compared to other forms of energy, oil has some important advanta...