![]()

Conservation at the crossroads: biological diversity, environmental change and natural resource use in Madagascar

Ivan R. Scales

In 2007, the Malagasy government published a five-year ‘Madagascar Action Plan’ for development. As well as setting out targets for economic growth and poverty reduction, it placed strong emphasis on the environment:

We will become a ‘green island’ again. Our commitment is to care for, cherish and protect our extraordinary environment. The world looks to us to manage our biodiversity wisely and responsibly – and we will. Local communities will be active participants in environmental conservation under the guidance of bold national policies.

(MAP, 2007, p97)

As a statement of intent, it certainly ticked all the right boxes, stressing the global significance of the island’s biodiversity but also balancing it with the need to involve local communities in the management of natural resources. However, to experienced observers of Madagascar’s environmental politics, this was nothing new. Over the past 30 years, the island has been a hotbed of conservation activity and never short of bold plans and policies.

At first glance, the case for urgent action seems clear. Madagascar is one of the most biologically diverse places on the planet, the result of 160 million years of isolation from the African mainland (Krause, 2005). It has over 13,000 species of plants (Phillipson et al., 2006), 700 species of vertebrates and more than 80 per cent of its species are endemic1 (Ganzhorn et al., 2001; Goodman and Benstead, 2005). This highly diverse flora and fauna is threatened by habitat loss and fragmentation, mostly due to forest clearance. The island has been classified as the world’s hottest biodiversity ‘hotspot’2 (Ganzhorn et al., 2001) and one of the world’s highest conservation priorities (Myers et al., 2000). As William McConnell (2002, p10) writes: ‘Few places on Earth evoke such simultaneous awe and consternation as Madagascar, a country with unique biological riches on a seemingly immutable path of impoverishment.’

As well as these environmental challenges, Madagascar must also deal with considerable and pressing human needs. In 2010, the island’s human population stood at over 20 million, with a growth rate of 2.9 per cent a year and a per capita Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of just US$ 421.3 Poverty has increased over the past 30 years, with a wide variety of socio-economic indicators declining and seven out of ten people living below the World Bank’s poverty line (World Bank, 1996). Over 70 per cent of Madagascar’s population is rural, relying mostly on subsistence agriculture or pastoralism and depending directly on the island’s ecosystems for a wide range of goods and services (Rasambainarivo and Ranaivoarivelo, 2006).

As if this didn’t make environmental management challenging enough, Madagascar also suffers from political instability, most recently in 2002 and 2009. In 2001, presidential elections were held. The then mayor of Antananarivo, Marc Ravalomanana, claimed he had won an outright majority in the first round of voting and alleged the election had been rigged. President Didier Ratsiraka refused to stand down, also claiming victory. This resulted in months of tension, strikes, street protests and violent outbreaks between supporters of the two politicians. President Ratsiraka established a power base in the eastern port city of Toamasina, cutting off vital supply routes to the capital. Through international pressure, the situation was eventually resolved, with the USA recognizing Ravalomanana as the new president in June 2002 and France offering Ratsiraka exile in Paris in July 2002. However, stability was short lived. In 2009, president Marc Ravalomanana was unconstitutionally ousted by a political movement led by the new major of Antananarivo, Andry Rajoelina. As of July 2013, Rajoelina was still in charge of the ‘High Transitional Authority’, with a timetable for new presidential elections yet to be decided. These problems follow decades of tumultuous national politics.

Madagascar thus presents a classic conservation and environmental management conundrum: how to protect biodiversity at the same time as delivering economic growth and raising people out of poverty in often difficult political circumstances. The challenge is considerable and it is perhaps not surprising that people writing about Madagascar often succumb to hyperbole. Madagascar’s environmental discourse is full of dramatic language and tales of impending crisis:

Twenty years ago, Britain’s Prince Philip described Madagascar as a nation committing ecological suicide. It was an apt assessment. The country seemed to be set on transforming its last remaining forests to ash and dumping its fertile but eroding soils into the Indian Ocean.

(Norris, 2006, p960)

However, the danger with such rhetoric is that it hides the fact that problems of poverty, environmental justice, natural resource use and biodiversity conservation are interlinked in complex ways. As this book shows, policy has often struggled to deal with such complexities.

Madagascar’s conservation landscape has changed dramatically over the past 30 years and environmental policy is at a crossroads. There has been a growing recognition that the creation of protected areas has imposed significant costs on rural communities due to loss of access to natural resources (Ferraro, 2002). Conservationists have tried to move beyond coercive legislation and a model of ‘fortress conservation’ to the greater involvement of communities in the management of natural resources (Pollini and Lassoie, 2011). Conservation organizations and government ministries have experimented with a wide range of community-based schemes, from agro-forestry (Pollini, 2009) to nature tourism and even awarding prizes for conservation competitions (Sommerville et al., 2010). In an attempt to reduce rural poverty and create revenue streams to pay for conservation activities, conservationists have begun to engage with incentive-based mechanisms and payments for ecosystem services. At the same time the government, as part of its ‘Durban Vision’, has recently tripled the extent of the island’s protected areas, creating 125 new protected areas and sustainable forest management sites (see Chapter 9 by Corson). Policy thus continues to reflect tensions between coercion and local participation, as well as between preservationist and utilitarian views of nature. Hundreds of millions of dollars have been spent, with mixed results (Kull, 1996).

It is thus a timely opportunity to ask what lessons can be learned from the experiences of biodiversity conservation and environmental management in Madagascar. How effective have different policies been? Who have the winners and losers been in attempts to conserve biodiversity? What are the implications of emerging forms of conservation for rural livelihoods? This book addresses these questions by pulling together a diverse range of experiences, drawing on insights from different academic disciplines (geography, anthropology, environmental history, political science, archaeology, palaeoecology and biology) and bridging the gap between research, policy and practice.

There has been a wealth of research on conservation-related issues in Madagascar. Publications such as Natural Change and Human Impact in Madagascar (Goodman and Patterson, 1997) and The Natural History of Madagascar (Goodman et al., 2004) are testament to the depth of scholarship. However, there have been major gaps, both in the academic literature and in our understanding. Perhaps the single biggest limitation to date has been the fact that the majority of academic literature on Madagascar can be classified under the banner of biological science, ranging from taxonomy to applied conservation biology. Without downplaying the importance of a solid understanding of ecological processes and biological diversity, it is clear that conservation and environmental management are as much about the choices that people make as they are about ecosystems or endangered species, and that the biological sciences therefore cannot provide all the answers (Balmford and Cowling, 2006; Mascia et al., 2003).

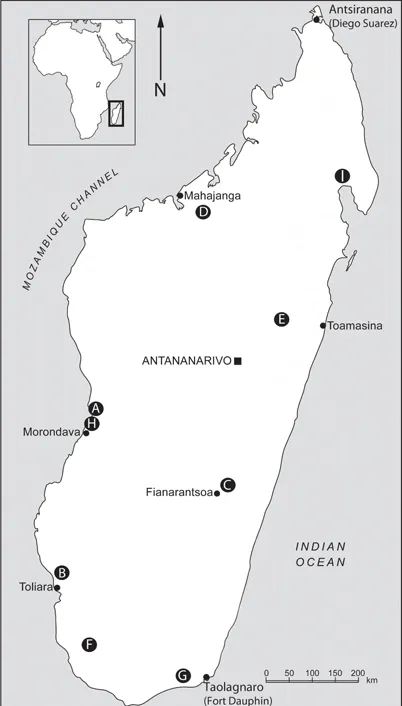

The past 15 years have seen a growing body of research that provides insights into the political, economic and cultural factors that have influenced the success and failure of conservation policy in Madagascar. The chapters in this book provide a summary of the key insights of this rich literature, as well as the remaining challenges and questions. I hope that this volume, as well as providing an overview and analysis of the major conservation and environmental management issues and dispelling a few myths in the process, stimulates conversation and debate. As readers will see, conservation in Madagascar is highly contested both ‘on the ground’ and in academic journals. I believe that recognizing this is crucial to the future of conservation on the island (Figure 1.1).

Outline

This book is divided into four parts. Part 1 sets the scene by presenting an overview of Madagascar’s biodiversity, long-term environmental changes and the impact of early human settlers. One of the main reasons Madagascar has received so much attention from international conservation organizations is its remarkable level of biological endemism. In Chapter 2, Jörg U. Ganzhorn, Lucienne Wilmé and Jean-Luc Mercier provide an introduction to the island’s biological diversity and its evolutionary history. In order to understand the origins of Madagascar’s remarkable flora and fauna, we must first look to its geological past. Continental drift over a period of 160 million years led to the island’s isolation and the majority of the taxa present on Madagascar evolved from colonization events rather than from any stock present on the landmass at the time of isolation. As well as geological isolation, biogeography and climate change have also played a key role in shaping Madagascar’s biodiversity. Madagascar is often described as ‘the island continent’ due to its wide range of environments – from lowlands to highlands, arid spiny forests to rainforests. The diversity of biomes, along with changes in vegetation in response to variations in temperature and rainfall, have resulted in high levels of micro-endemism.

Madagascar’s flora and fauna have undergone extensive changes over the past 10,000 years. The island has experienced a significant number of extinctions, as well as considerable land cover change. This has been the result of a complex set of factors including climate variability and the impacts of human activities. In Chapter 3, Robert E. Dewar focuses on Madagascar’s Holocene palaeo-environment, paying particular attention to the evidence for the impact of early human settlers on the island’s flora and fauna. His chapter discusses new evidence that pushes back the date of human arrival, with archaeological traces of foragers visiting rock shelters in northern Madagascar from at least 2000BC. The chapter also dispels a few myths about the extent to which early human settlers impacted on the island’s flora and fauna, challenging overly simplistic stories and questioning the problematic nature of ideas of the ‘original’ vegetation of Madagascar, especially given the incompleteness of our evidence of both the present and the past. Until recently, it was supposed that the first people on Madagascar imported fire and the result was a ‘giant fire’ that was utterly destructive to a forested but fragile landscape. However, palaeoecological research shows that periodic fires have been an important element of many Malagasy ecosystems for tens of thousands of years. Dewar persuasively argues the importance of recognizing the complexity of social and environmental systems and acknowledging the limitations of the tools at our disposal for exploring them. More research is required to piece together accurate place-specific accounts of ecological change and human impacts, and major puzzles remain.

Figure 1.1 Map of Madagascar showing the location of key case studies discussed in the book. A: Dry-deciduous forests of western Madagascar (Chapter 5); B: Spiny forests of southwestern Madagascar (Chapter 5), including Ranobe PK32 protected area (Chapter 10); C: Eastern rainforest including Fandriana-Vondrozo corridor and Ranomafana National Park (Chapters 8 and 9); D: Communities near Ankarafantsika (Chapter 8); E: Eastern rainforests including Ankeniheny-Zahamena corridors (Chapters 8 and Chapter 9), the ICBG-Madagascar bioprospecting project (Chapter 12) and Didy village conservation agreements and ‘Alternatives to Slash-and-Burn’ (Chapter 13); F: Mahafale Plateau (Chapters 8 and 14); G: Ankodida community-managed protected area (Chapter 10); H: Baobab Avenue (Chapter 11); I: Makira REDD+ project (Chapter 13)

Unfortunately, conservation planning in Madagascar has often been based on received wisdoms and untested assumptions. In Part 2, the book explores a set of ecological and social issues that have often been misunderstood and misrepresented. Chapter 4, by William J. McConnell and Christian A. Kull, tackles the debate surrounding the extent of Madagascar’s for...