![]()

1 PARADIGM, PHILOSOPHY AND GEOGRAPHIC THOUGHT

Milton E. Harvey and Brian P. Holly

Introduction

Geographic thought, at any point in time, is a manifestation of the interaction between the prevailing philosophical viewpoints and the major methodological approaches in vogue. Because of the extreme diversity of viewpoints on both philosophy and methodology, there has been a constant extension, and even a shift, in the focus of the discipline. In the last few decades many papers, monographs and books have been written either about specific aspects of these shifts or about the major trends in these shifts. Ley and Samuels’ Humanistic Geography (1978) and Peet’s Radical Geography (1979), are examples of the former. Whereas Hartshorne’s Nature of Geography (1961), James’s All Possible Worlds (1972) and James and Martin’s The AAG: The First Seventy-Five Years (1979) are examples of the latter. In different forms, all these authors have attempted to organise and present specific viewpoints on the history, philosophy, the focus and the methodology of geography. Pervading all these are attempts to clarify the influence of philosophical and paradigmatic viewpoints on geographic thought. Because of the pedagogical aim of this book, the first part of this chapter will explore this interrelationship. Later, we discuss the major paradigmatic developments in geography. In the final section, the trends toward strong philosophical viewpoints within emerging geographic paradigms are explored.

Paradigm, Philosophy and Thought

Ever since David Harvey’s paper on revolution and counter-revolution in 1972, the use of the word paradigm has become fashionable in geography as well as having become a pivotal concept for courses in geographic thought on both sides of the Atlantic. Thomas Kuhn has become as familiar to students of geography as Hartshorne or Humboldt! Kuhn, in his classic book, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, defined paradigm as ‘the entire constellation of beliefs, values, techniques, and so on shared by the members of a given community’ (1970a, p.175). In an earlier articulation of paradigm (the 1962 edition of The Structure of Scientific Revolutions), Kuhn uses this concept in at least 21 different ways (see Masterman, 1970, pp.61–5). These were collapsed into three paradigm types by Masterman: the metaphysical paradigms or metaparadigms, the sociological paradigms and the artefact or construct paradigms. Very briefly, the meta-paradigms present a total global view of science. It is a gestalt view; a Weltanschauung (or map). Such a map, Ritzer wrote, ‘allows the scientist to explore the vast and complex world otherwise inpenetrable were be to explore randomly’ (Ritzer, 1975, p.4). Such a paradigm performs three basic functions:

1. | It defines what entities are (and are not) the concern of a particular scientific community. |

2. | It tells the scientist where to look (and where not to look) in order to find the entities of concern to him. |

3. | It tells the scientist what he can expect to discover when he finds and examines the entities of concern to his field (Ritzer, 1975, p.5). |

It is the broadest area of consensus in a discipline, and it defines the subareas of research. In contrast, the sociological paradigm is grounded on concrete scientific achievement; a universally recognised scientific achievement. The third, and narrowest, is the construct paradigm. Here specific entities such as a textbook, an instrument, or a classic work are viewed as paradigms. Conceptually, the construct paradigm is largely subsumed in the sociological paradigm and this, in turn, is essentially subsumed in the metaparadigms. Because of such a nesting, the construct paradigm must be central to the development of paradigmatic sciences. In fact, Masterman argues that it is the construct paradigm that is central to Kuhn’s formulation:

If we put what a Kuhnian paradigm is, Kuhn’s habit of multiple definition poses a problem. If we ask, however, what a paradigm does, it becomes clear at once … that the construct sense of ‘paradigm,’ and not the metaphysical sense of metaparadigm, is the fundamental one. For only with an artefact can you solve puzzles … It remains true that for any puzzle which is really a puzzle to be solved by using a paradigm, this paradigm must be a construct, an artefact, a system, a tool; together with the manual of instructions for using it successfully and a method of interpretation of what it does (Masterman, 1970, p.70).

In his ‘Reflection on My Critics’, Kuhn agrees with Masterman that construct paradigms are central to his thesis. ‘If I could’, he noted, ‘I would call these problem-solution paradigms, for they are what led me to the choice of the term in the first place’ (Kuhn, 1970c, p.277). Because of the subject-specific nature of problem-solutions in the framework of the construct paradigm, Kuhn substituted the phrase ‘disciplinary matrix’ for ‘a paradigm’ or ‘a set of paradigms’. He amplified his preference for disciplinary matrix thus:

‘disciplinary’, because it is common to the practitioners of a specified discipline; ‘matrix,’ because it consists of ordered elements which require individual specification. All of the objects of commitment described in my book as paradigms, parts of paradigms or paradigmatic would find a place in the disciplinary matrix, but they would not be lumped together as paradigms, individually or collectively (Kuhn, 1970c, p.271).

This discussion of the concept of paradigm creates the proper backdrop for a discussion of paradigms in geography. However before such an exercise can be fruitfully attempted, a few other issues pertinent to this concept must be explored. These are posed as questions: Is a scientific discipline, by definition, a single paradigm? How are new paradigms created? Is a paradigm equivalent to a theory? Is a paradigm associated with a specific philosophy?

Single or Multiple Paradigms

On the question of single or multiple paradigm disciplines, Kuhn’s earlier formulation was unclear. Masterman wrote thus: ‘As I see it, he fails to distinguish from one another these relevant states of affairs, which I will call respectively non-paradigm science, multiple-paradigm and dual-paradigm science’ (Masterman, 1970, p.73). Briefly, a discipline is in a non-paradigmatic state when there are no paradigms and the scientists in a particular discipline cannot differentiate the subject matter of their discipline from that of other allied disciplines. In contrast, a dual-paradigmatic science exists just prior to a revolution which leads to the emergence of a single paradigm. During this period, the two paradigms compete for control. In a stages framework, a discipline moves from the non-paradigmatic state through the competitive dual-paradigmatic stage to the single-paradigm stage. This simple evolutionary framework is, however, disrupted by the possibility that certain disciplines, especially in the social sciences, may be multiple-paradigm sciences. In a multiple-paradigm science, many paradigms are competing for hegemony in the field. As Ritzer observed, ‘one of the defining characteristics of a multiple-paradigm science is that supporters of one paradigm are constantly questioning the basic assumptions of those who accept other paradigms’ (Ritzer, 1975, p.12). Masterman has vividly summarised the attributes of such a science:

Here, within the sub-field defined by each paradigmatic technique, technology can sometimes become quite advanced, and normal research puzzle-solving can progress. But each sub-field as defined by its technique is so obviously more trivial and narrow than the field as defined by intuition, and also the various operational definitions given by the techniques are so grossly discordant with one another, that discussion on fundamentals remains, and long-run progress (as opposed to local progress) fails to occur (Masterman, 1970, p.74).

Masterman’s discussion of multiple paradigms has been criticised on the grounds that she regards them as a stage in the emergence of a paradigmatic science. Many social scientists contend that paradigms do co-exist in a discipline. Merton recently defended this co-existency on the ground that plurality of paradigms does provide the atmosphere for the generation of,

a great variety of problems for investigation instead of prematurely confining inquiry to the problematics of a single, assumedly overarching paradigm … The exclusive adherence of a scientific community to a single paradigm, whatever it might be, will preempt the attention of scientists in the sense of having them focus on a limited range of problems at the expense of attending to others (Merton, 1976, pp.138–9).

Rather than social scientists, such as sociologists, striving for a unified paradigm, Merton rightly argues that energies should be directed toward the identification of the capabilities and weaknesses of each paradigm. A similar view about the need for this plurality of viewpoints has been stressed by Bartels:

Plurality of points of view at any one time is … unavoidable in a discipline and our reaction to this should not be one of dismay but a recognition of the need for a corresponding expansion of democratic forms of pluralistic co-existence in science which accepts these situations of conflict between different ‘statements of truth’ (Bartels, 1973, p.24).

Bartels, however, cautioned that such a plurality should not exist to such a degree that the subdisciplines are closer to neighbouring disciplines. Furthermore, he argued that the existence of such plurality should not prevent the continued dissemination of a clearly defined public image of that discipline. When both occur, the discipline is in deep trouble!

From the above discussion, it is evident that there is no consensus about the stages in the paradigmatic evolution of a scientific discipline. In fact, it may even be argued that a science may move from a pre-paradigmatic to a multiple-paradigmatic science, and from the multiple paradigm state to either a single- or a dual-paradigm science. It is probably impossible to develop a staged unidirectional formulation for the evolution of any discipline, particularly the social sciences, and we do not intend to make such an attempt. Of more relevance to us is the question of how to determine whether a science is paradigmatic.

Ritzer has identified certain attributes of a paradigm: an exemplar, image of the subject matter, theories and methods (Ritzer, 1975, pp.25–7). As defined by Kuhn himself, exemplars are:

The concrete problem-solutions that students encounter from the start of their scientific education, whether in laboratories, on examinations, or at the ends of chapters in science texts. To these shared examples should, however, be added at least some of the technical problem-solutions found in the periodical literature that scientists encounter during their post-educational research careers and that also show them by example how their job is to be done (Kuhn, 1970a, p.187).

To Kuhn, exemplars are those fundamentals learned by the practitioners of that discipline or viewpoint. The image of the subject matter is the single overriding theme that is most characteristic of the dominant exemplar; it is the basic subject matter of that viewpoint. In addition to exemplar and image of the subject matter, a paradigm must also include a constellation of theories and methods. An example from Ritzer’s discussion of the social facts paradigm will help elucidate on these components.

Exemplars: Durkheim’s The Rules of Sociological Method (1938) and Suicide (1951)

Image of the Subject Matter: Social Structure and Social Institutions

Theories: Structural-Functionalism

Methods: Questionnaires and/or Interviews

These attributes of a paradigm are later used in our discussion of paradigms in geography.

How are New Paradigms Created?

In the traditional Kuhnian formulation, it is not the accumulation of knowledge that causes changes in science. Such changes are caused by a revolution. In this formulation change is effected through a linkage of events: Paradigm A → Normal Science → Anomalies → Crisis → Revolution → Paradigm B. Briefly, after a paradigm has emerged, there is generally a period of normal science when scientists working within that paradigm accumulate knowledge. This research expansion results in the gradual accumulation of anomalies which cannot be explained or solved by the existing paradigm. As these increase, a crisis stage is reached as discontent with the paradigm mounts. Ultimately, this results in a revolution. When comparing his views on scientific revolutions to those of Sir Karl Popper, Kuhn clearly reiterated this approach to scientific progress:

Both of us reject the view that science progresses by accretion; both emphasize instead the revolutionary process by which an older theory is rejected and replaced by an incompatible new one; and both deeply underscore the role played in this process by the older theory’s occasional failure to meet challenges posed by logic, experiment, or observation (Kuhn, 1970b, pp.1–2).

As David Harvey rightly noted, the revolutionary process stressed by Kuhn and Popper only gains acceptance if ‘the nature of the social relationships embodied in the theory are actualized in the real world’ (Harvey, 1972, p.4).

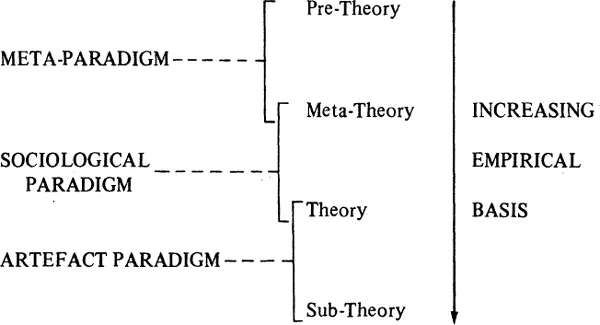

Paradigm and Theory

In the footnote designed to elucidate on his use of theory in the above quotation, Kuhn wrote thus: ‘elsewhere I use the term “paradigm” rather than “theory” to denote what is rejected and replaced during scientific revolutions’ (Kuhn, 1970b, p.2). But as Masterman observed, paradigm and theory are not the same! She contended that the meta-paradigm and the sociological paradigm ‘are prior to theory’ (Masterman, 1970, p.66). Such paradigms precede or are combinations of law, theory and methodology. In contrast, the construct paradigm, Masterman asserts, can be less than or equal to a theory. The distinction between theory and paradigm is also noted by Ritzer: ‘theories are not paradigms, but only one aspect of a far broader unit that is a paradigm’ (Ritzer, 1975, p.20). In summary, although some theories can be equivalent to paradigms (as in the physical sciences), generally, this is not the case. The broad relationships between paradigms and theory are summarised below:

Paradigm and Philosophy

Broadly, an individual’s philosophy is the totality of his basic beliefs and convictions. Titus has presented the following definitions of philosophy (Titus, 1964, pp.6–8):

i. It is a personal attitude toward life and the universe. In amplifying this, he wrote that ‘philosophy is in part the speculative attitude that does not shrink from facing the difficult and unsolved problems of life’ (Titus, 1964, p.6).

ii. It is a method of reflective thinking and logical inquiry. It is the attempts by the individual to logically understand a specific problem. It involves a critical evaluation of the facts.

iii. It is an attempt to develop a view about the whole system.

iv. It is the ‘logical analysis of language and the clarification of the meaning of words and concepts’ (Titus, 1964, p.8).

A better insight can be gained about philosophy and philosophical thinking when it is contrasted with science. To quote from Titus:

Philosophy … attempts to gain a more comprehensive view of things. Whereas science is more analytic and descriptive in its approach, philosophy is more synthetic or synoptic, dealing with the properties and qualities of nature and life as a whole. Science attempts to analyse the whole into its constituent elements or the organism into organs; philosophy attempts to combine things in interpretative synthesis and to discover the significance of things (Titus, 1964, p.97).

The above discussion underscores the functions of philosophy as a speculative, descriptive, normative and analytical discipline that investigates the presuppositions and the scientific work of practitioners in a discipline. Philosophy evaluates what has been done, and from there, it may suggest what should be studied by a discipline. This implies that philosophy not only evaluates but also creates a framework for research. It is an evaluation of how the discipline has conducted research; what questions the researchers have asked, and how these questions have been investigated within the framework of both normative and societal structures. In this context, Harris’s comment is appropriate:

To reveal what criteria are presupposed is not by itself sufficient. It is further necessary to find out whether they are mutually consistent, and, if not, how they require modification. When this is determined we say not only what is presupposed in fact but what ought to be presupposed to make our thought and action consistent (Harris, 1969, p.7).

Central to any philosophical viewpoint is the individual’s belief system. Because of the diversity of beliefs, there is a diversity of philosophies; whether in the commentaries made on what is being done or regarding what should be done and how it should be done. This implies that philosophies are not equivalent to paradigms. A set of philosophies with sufficient communality of focus and approach, and a large group of practitioners, may constitute a pa...