![]()

Part I

PROBLEMATIZING ETHICAL TRADE

![]()

1

ETHICALITY IN THE GLOBAL FOOD SYSTEM

Introduction

As the effects of ‘triple crises’ – of food, climate and finance – reverberate through the international food system, the need to reform food production, trade and consumption along more ethical and sustainable lines is as urgent as ever. Emerging as a key element in the transformation of an increasingly globalized agri-food system, ethical trade refers to a ‘variety of approaches affecting trade in goods and services produced under conditions that are socially and/or environmentally as well as financially responsible’ (Blowfield, 1999, p754). Consumers around the world have become increasingly concerned about inequalities within the global food system, the environmental effects of agriculture and the social effects of the globalization of food production (see McMichael, 2000a), drawing attention to the poverty and livelihood implications that the current political–economic climate of globalization, neo-liberalism, structural adjustment, corporatization and the de-regulation of world trade has had for producers, particularly in the global South.1 Ethical sourcing standards – such as the UK’s Ethical Trading Initiative, GlobalG.A.P. and Fair Trade – have emerged as powerful mechanisms through which public awareness of these issues is addressed.

For social researchers, policy-makers and activists interested in the nexus between sustainable development, social justice, global trade and South–North relations, there is intense debate over the capacity of Northern-led ethical trade schemes to enhance the livelihoods of Southern farmers on whose labour the export of high-value horticultural foods depends (Freidberg, 2003a). In particular, African smallholders2 – defined here as producers who grow relatively small volumes of produce on small plots of family owned and managed land, often combining production of an export commodity with other livelihood activities – are key stakeholders in ethical trade initiatives. In Kenya, where the horticultural industry has a poor track record in labour rights and environmentally sustainable production, smallholders have been inundated with many codes and standards for environment, food safety, social welfare, labour practice and quality3 that must be met if they wish to export their fresh products to Europe (Barrientos and Dolan, 2006).

Ethical trade is also highly gendered. In Kenya and across Africa, approximately two-thirds of smallholder labour is done by women (English et al., 2004; NRI, 2006). Women are particularly active in the production of value-added, labour-intense crops such as French beans and cut flowers and, as such, are finding themselves governed by multi-stakeholder codes for ethical trade that are unsuited to their needs. Gender impacts, while increasingly acknowledged as important to assessing the overall effectiveness of ethical trade, often remain marginal to questions of cost and productivity. Women smallholders remain one of the most marginalized groups in Africa, based on their often informal, casual and seasonal employment status, low levels of participation in defining and negotiating standards, and deeply entrenched gender inequalities at the cultural level (Barrientos et al., 2001a; Barrientos et al., 2003; Blowfield et al., 1999; Smith, 2013; Smith and Dolan, 2006; Tallontire et al., 2005). But making the connection between women, smallholder farming and sustainable livelihoods has been a slow process for many ethical sourcing schemes.

A central issue is that, while trade in ‘ethically produced’ food has increased alongside the exponential growth in private ‘ethical’ standards, certifications and accreditation schemes across the world, so have concerns as to the ‘fairness’ of such trends for producers located in the global South. Over 15 years ago, Michael Blowfield – a leading scholar on ethical trade and corporate social responsibility (CSR) – warned that:

Without greater participation from developing countries, and particularly a shift in decision-making from the North to the South, ethical trade will at best be paternalistic and at worst harmful to those it is intended to benefit. Indicators of achievement will reflect the values and concerns of Northern companies and consumers, and the instruments employed will remain those that Northern stakeholders understand, rather than those best able to identify the concerns and aspirations of people in the South. One of the successes of ethical trade is that it has opened the North’s eyes to conditions in the South, but it will require belief in the South’s capacity and ability to define its own ethical goals if Northern companies, civil society organisations and consumers are to relinquish the control over the ethical trade movement that they currently exert.

(Blowfield, 1999, p767)

This critique remains pertinent today, fuelled by old and new ‘crises’ alike. The global ‘food crisis’ of 2008 had resulted in an 83 per cent rise in food prices (since 2006, see Lawrence et al., 2010; Rosin et al., 2011), and contributed (among other things) to the undernourishment of 870 million people by 2012 (FAO, 2013). This event alone has reinvigorated long-standing debates around the justice credentials of a globalized food system in which a well-fed North (consumers, corporations, regulatory institutions) continues to dictate the terms of production and trade for countries in the developing South. Older problems associated with neo-liberalism (import dependence, agricultural commodification, rural/peasant displacement), failed green revoloutions (technological dependence, corporatization, ecological decline), poverty and inequality (food insecurity, conflict and insecurity) persist alongside a host of recent developments now central to the food–ethics conversation: the rapid rise of agro-fuel production; extensive ‘land grabbing’ in the South; financialization and food price speculation; climate change and ‘food miles’; the ‘nutrition transition’ (i.e. the trend from grain-based to meat/oil/fat/sugar-based diets around the world); food security and food sovereignty; and the dramatic implications that peak oil, peak phosphorus and peak water will have for productivitist agriculture.4

The global financial crisis of 2009 has exacerbated these concerns. In a recent Oxfam report it was found that women in the global South are paying the biggest price. As falling demand squeezes supply chains, the jobs of already vulnerable women workers are often the first to go, with negative implications for women’s livelihoods, rights and the well-being of families. Economic stimulus packages tend to favour jobs for men, and poor regulation or enforcement of laws often mean poor labour rights for women (see Emmett, 2009). And in early 2013, the European horsemeat scandal made headlines reminiscent of the BSE crisis of the mid-1990s, again drawing attention to the complex nature of regulating safety, risk, traceability and accountability in complex international food chains. Similarly, the 2013 Bangladeshi clothing factory tragedy5 (in which 112 garment workers, mostly women, died when a factory on the outskirts of Dakar burned down) has re-alerted consumers to safety and labour rights issues in global supply chains. In such a context – and with so many competing challenges to the economic, social and environmental sustainability of the global food system – the place of voluntary, partial (and costly) ethical standards is contentious.

The vulnerability of smallholder women farmers in the global South, and the negative impacts these crises have had on their ability to sustain livelihoods, have been widely documented (see Asian Development Bank/de Schutter, 2013; UN General Assembly, 2011a,b, 2012). This has opened up space for a revived articulation of the perspectives and experiences of those most disadvantaged by the above global trends. This is occurring at multiple levels of governance. For example, the UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food has noted that ‘the recognition that women may have different priorities to those of men leads to fundamental questions about the type of support they should be provided’ (UN General Assembly, 2012, p17). Likewise within the recent UN ‘green economy’ debate, it is increasingly accepted that ‘there has to be recognition of [women’s] knowledge and their contribution to the production, preparation and distribution of food’ (Nobre/FoEI, 2011, p3), although the United Nations Research Institute for Social Development (UNRISD) has warned that we must continue to question whose knowledge counts, who has space to act and influence, and which practices ultimately prevail within any form of future ‘green economy’ (Cook and Smith, 2012). Within both green economy and ‘right to food’ debates, each increasingly posits local-level knowledge and practices as an important source of learning for national and global level sustainability strategies.

At the grassroots level, global social movements have consistently demanded that appropriate agricultural policies must consider the specific needs of women and peasants (i.e. smallholder farmers), alongside guaranteeing people’s rights to land, family farming and agro-ecology.6 Fair and ethical trade organizations, as well as companies with ethical sourcing at their core, are more than ever reasserting their commitment to improve the ethical performance of global horticultural trade, often in the name of pro-poor development, empowerment, sustainable livelihoods, poverty reduction and equity (see Lewis, 2011; Reed et al., 2012). The Fairtrade Foundation exemplifies this general trend, in arguing that:

The previous decade has seen phenomenal growth of the scope and market of Fairtrade and a huge interest in ethical standards in general. This level of growth, alongside the increasing levels of engagement of other key stakeholders, provides Fairtrade with a number of opportunities and challenges to ensure that smallholders are integrated into global supply chains in a manner which facilitates producer empowerment and development … To move forward it is important that buyers perceive farmers as active partners and not passive beneficiaries.

(Fairtrade Foundation, 2012, pp5, 7)

Box 1.1 The paradox of ethical trade, and the focus of this book

The socio-political context described above has been important for carving a space for livelihoods research in the field of ethical sourcing, and for highlighting the need for ethical trade to give greater weight to the knowledge and experiences of smallholder women involved in horticultural production, consumption and trade in the global South. Ethical trade is widely criticized for being highly gendered, and for institutionalizing the ethical values of consumers, the priorities of NGOs and governments and, most of all, food retailers. While some participants in ethical trade have benefitted in some labour-related aspects, these are extremely dependent on commodity, country context, employment status and gender. And although some ethical trade standards reflect the concerns of women smallholder farmers in the global South, most do not (Barrientos and Smith, 2006; Nelson et al., 2005). In reality, the knowledge and labour of women smallholders are fundamental to food security and the success of global trade, but their empowerment within existing ethical trade supply chains is often low. This presents a paradox for ethical trade regulations which aim to improve the livelihoods of Southern smallholder women.7 This book asks: How do women smallholders construct ‘ethicality’ in their food networks in relation to sustainable livelihoods, and how do these understandings compare with those currently prioritized in regulatory ethical trade models?

Defining ‘ethical trade’

The term ‘ethical trade’ includes a broad range of voluntary ethical ‘sourcing’ initiatives, including multi-stakeholder ethical trade and fair trade. First coined by Welford (1995, cited in Blowfield and Jones, 1999, p1), the term ‘ethical trade’ was used to describe a ‘step towards sustainability; a “more holistic and ethical approach to doing business” that values both societal and environmental impact, and restructures North–South relations’. In addition to regulating the environmental conditions of food production, ethical trade aims to ‘guarantee core labour and human rights standards to their workforce’ (Blowfield, 1999, p753). By incorporating environmental and social sustainability into trade regulations, ethical trade aims to address concerns that food producers living in the global ‘South’ are systematically disadvantaged by food production and consumption relationships (Blowfield, 1999; Fox and Vorley, 2006; Hughes, 2007; Raynolds, 2000). In horticulture, these standards are applied to global supply chains where distant producers (e.g. in Africa) trade their fresh produce with supermarkets or other retailers located in the global North (i.e. the UK or US).

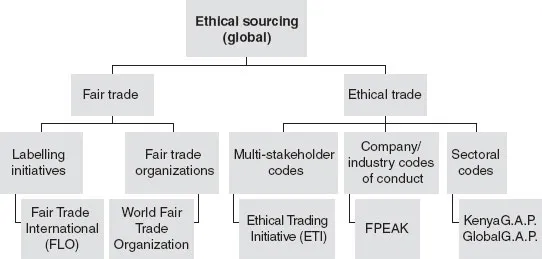

Fair trade can be separated into (i) fair trade labelling initiatives and (ii) alternative trade organizations (ATOS). In Kenya, ethical trade has emerged via three routes: (i) internationally as independent multi-stakeholder codes (as formalized in the UK’s ‘Ethical Trading Initiative’, or ETI); (ii) via supermarkets and their agents (such as retailer contractual agreements and GlobalG.A.P./KenyaG.A.P. standard); and (iii) sectorally via trade associations (including ethical sourcing agreements and supply chain regulation) (Barrientos and Dolan, 2006). All of these use some form of code of conduct to establish standards, which are monitored and verified through audit processes (Hughes, 2007, p177). Figure 1.1 simplifies the structure of formalized ethical sourcing schemes.

Figure 1.1 Types of ethical sourcing initiatives

Source: Author’s own work.

Ethical sourcing schemes are ‘strategic intervention[s] for addressing the social, economic, and environmental injustices of global agriculture’ (Neilson and Pritchard, 2010, p1). While they draw selectively from diverse theoretical and ideological perspectives on connections between environment, social justice, economics, science, politics and culture (see Barry and Doran, 2006), many of the theoretical and practical drivers of fair trade also apply to ethical trade. Discursively, both focus on ‘how historically exploitative producer consumer chains can be refashioned around ideas of fairness and equality’ (Raynolds, 2002a, p405). Values of fairness, equality, poverty reduction, sustainability, rights, justice, partnership, community, development and well-being certainly underpin the ETI Base Code and Fair Trade (Blowfield, 2003a; Dolan, 2008). Environmental impact and quality concerns drive GlobalG.A.P. and other supermarket and industry codes of conduct.

However, descriptive accounts of fair and ethical trade in both North and South reveal that they differ in their mechanisms for regulating supply chains, and in their emphases on equity and sustainability and methods for achieving these (Raynolds, 2007). For example, fair trade schemes had their beginnings in grassroots alternative trade organizations often in the global South, and seek to establish economic justice and to transform North–South trade through developmental objectives of producer empowerment, poverty alleviation, international trade reform and consumer activism (World Fair Trade Organization and Fairtrade Labelling Organizations International, 2009).

Ethical trade, too, has been popularized as part of poverty alleviation, human rights and economic development agendas (Dolan, 2005a), but in contrast to fair trade, is more commonly directed by multinational corporations and global supermarket chains looking to find a way of regulating and marketing their produce to increasingly critical consumers in developed countries such as the UK and the US. It normally refers to more modest codes of labour practice which denote minimum labour standards (and occasionally include environmental standards) within an existing trade model (Barrientos and Dolan, 2006; Barrientos et al., 2000; Blowfield, 1999, 20...