![]()

1

Establishing the Presence of Workplace Bullying in India

Background of the Study

The first survey to establish the presence of interpersonal bullying at work in India, using the Work Harassment Scale (WHS) (Bjorkqvist and Osterman 1992), was undertaken in the Indian ITES-BPO sector by D’Cruz and Rayner in 2009 (D’Cruz and Rayner 2010). The WHS provides a set of 24 questions concerning the experience of negative behaviours at work and asks respondents to recall the frequency (if any) with which they have encountered such treatment during the previous six months. It allows for bullying to be measured via behavioural experiences rather than subjective interpretations. In so doing, it counters the possibility of people continuing to suffer the harm associated with bullying due to their personal definitions of their experiences (Einarsen et al. 2011a; Hoel, Faragher and Cooper 2004). Recognizing that the WHS embodies this important feature and hence affords the opportunity to gain more accurate insights, D’Cruz and Rayner (2010) chose to use this scale in their survey. The WHS was used in its original form, as the population it was administered to was fluent in English and issues of item interpretation on account of language did not arise.

The survey was conducted in six geographical locations (namely, Bangalore, Chennai, Hyderabad, New Delhi and National Capital Region [NCR], Mumbai, and Pune) with employees working at all levels within the organizational hierarchy. Given the reluctance of Indian work organizations to provide access to their employees owing to the nature of the research problem, the researchers relied on snowball sampling to complete the study. However, snowball sampling incorporated a purposive element to ensure sector-specific proportionate representation of geographical location, nature of work and position in employer organization. Respondents participated in an individual interview, conducted by a research assistant, during which socio-demographic details were gathered and the WHS was administered. Voluntary participation, informed consent and the option of withdrawing during the interview as well as the maintenance of confidentiality ensured ethical practices within the research process. Descriptive and inferential statistics were applied to the data, via the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) (D’Cruz and Rayner 2010).

Respondents’ Socio-demographic Details

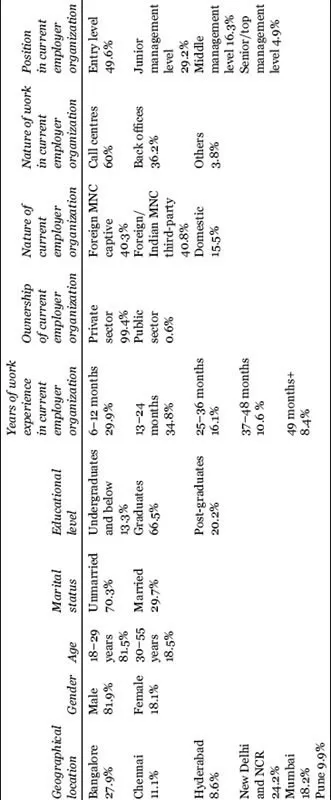

A total of 1,036 respondents participated in D’Cruz and Rayner’s (2010) study. Of this, 27.9 per cent of the respondents were from Bangalore, 11.1 per cent from Chennai, 8.6 per cent from Hyderabad, 24.2 per cent from New Delhi and NCR, 18.2 per cent from Mumbai, and 9.9 per cent from Pune. Of the 848 (81.9 per cent) men and 188 (18.1 per cent) women, 81.5 per cent were between 18 to 29 years of age and 70.3 per cent were unmarried. Most respondents (66.5 per cent) were graduates, of whom 11.4 per cent had professional degrees. Post-graduate qualifications were held by 20.2 per cent of the sample.

Respondents’ work experience in the ITES-BPO sector varied within a small number of years, with 61.2 per cent of the respondents reporting between 13 and 48 months (approximately 20 per cent in each group of 12 months). Only 16 per cent had more than five years experience in this sector. In terms of work experience in the current organization, most respondents belonged to the 6–12 months (29.9 per cent) or 13–24 months (34.8 per cent) groups. Only 8.4 per cent had worked in their current organization for more than four years.

Private sector employment accounted for 99.4 per cent of the respondents. In terms of the nature of the employer organization, 40.3 per cent were employed by foreign multinational corporation (MNC) captives, 40.8 per cent by foreign/Indian MNC third-party and 15.5 per cent by domestic organizations. Call centre employees accounted for around 60 per cent of the sample while 375 (36.2 per cent) performed back office tasks, and the remainder split between several functions. Hierarchically, 49.6 per cent worked at the entry level, 29.2 per cent at the junior management level, 16.3 per cent at the middle management level, and 4.9 per cent at the senior management level (see Table 1.1 for a summary of the respondents’ socio-demographic details).

Respondents’ socio-demographic details reflect known trends in the ITES-BPO sector (see D’Cruz and Noronha 2010), suggesting a valid sample.

Findings

Establishing the maximum frequency reported within the 24 bullying behaviours of the WHS for each respondent, D’Cruz and Rayner (2010) found almost all respondents (94.6 per cent) describing some experience of workplace bullying. Although for many of them this was not frequent, 23.7 per cent of the sample reported at least one behaviour as being experienced very often (Table 1.2).

Using ‘often’ and ‘very often’ as the closest equivalents of weekly experiences, D’Cruz and Rayner (2010) found that 42.3 per cent of the respondents could be considered to have been bullied. This is a far higher incidence than one would find in the Nordic countries (where typically 2–5 per cent are found to be bullied, as reported by Mikkelsen and Einarsen [2001] and Mathiesen, Einarsen and Mykletun [2008]) and in the UK (where Rayner’s [2009] recent study found 27.6 per cent of the total respondents with a weekly bullying experience or more). Even though respondents were not asked to label themselves as bullied or not, the reports of interpersonal negative behaviours were relatively high. Rates were comparable to those from a US study undertaken by Lutgen-Sandvik, Tracy and Alberts (2007). Bilgel, Aytac and Bayram (2006) reported very high rates in a Turkish study, but it is not possible to establish exact equivalence here due to measuring differences.

Bjorkqvist and Osterman’s coding system was applied, wherein each respondent’s score per WHS question was added and the total score so generated was then divided by 24 to determine the mean score (D’Cruz and Rayner 2010). Following Bjorkqvist and Osterman’s method, each respondent was classified into a severity level. Of the total sample, 44.3 per cent experienced workplace bullying, with most respondents falling into the mild or moderate bullying category. Two respondents reported having been very severely bullied (Table 1.3).

TABLE 1.1

Socio-demographic Details of 1,036 Respondents

TABLE 1.2

Frequency of Experiencing Bullying Behaviour

| Frequency of experience | Percentage of sample where this was their maximum score |

Never | 5.4 |

Seldom | 15.3 |

Occasionally | 36.9 |

Often | 18.6 |

Very often | 23.7 |

Source: D’Cruz and Rayner (2010: 10).

TABLE 1.3

Severity of Bullying Experienced

| Level of severity | Number of respondents | Frequency percentage |

0.0–0.5 (No bullying) | 577 | 55.7 |

0.6–1.0 (Mild bullying) | 253 | 24.4 |

1.1–2.0 (Moderate bullying) | 163 | 15.7 |

2.1–3.0 (Severe bullying) | 41 | 4.0 |

3.1–4.0 (Very severe bullying) | 2 | 0.2 |

Total | 1,036 | 100 |

Source: D’Cruz and Rayner (2010: 11).

Using an r2 cut-off of 0.2, D’Cruz and Rayner (2010) did not find any significant correlations between the severity scores of respondents and their gender, age, educational level, years of work experience, income, and position in employer organization. There were no significant differences between geographical location, ownership of employer organization, nature of employer organization, and nature of work on the one hand and the severity of bullying reported on the other.

Bullying lessened as one went up the organizational hierarchy, being reported by 48.8 per cent of the respondents at the entry level, 43.4 per cent at the junior management level, 37.9 per cent at the middle management level, and 25.5 per cent at the senior management level. The most frequent source of bullying was superiors (73.1 per cent), followed by peers (37.3 per cent) and subordinates (21.8 per cent). More detailed analysis showed that it was very rare for subordinates to bully on their own, with managers also being reported as a source of bullying by 94 per cent of those bullied by subordinates. When peers were reported as sources of bullying, managers were also reported in 74 per cent of these cases. Cross-level co-bullying was thus apparent (D’Cruz and Rayner 2010).

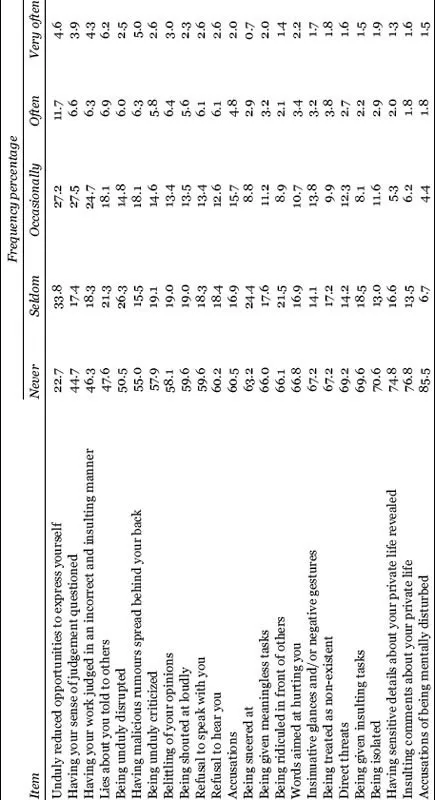

A behavioural accounting exercise via an item-wise analysis was completed (Table 1.4). ‘Reduced opportunity to express yourself’, ‘having your sense of judgement questioned’, ‘having your work judged in an incorrect and insulting manner’, and ‘lies about you told to others’ were the bullying behaviours that respondents reported most frequently. That is, for each of these four items, the cumulative frequency of respondents’ answers in terms of ‘occasionally’, ‘often’ and ‘very often’ was 30 per cent or more. In the cases of ‘being unduly interrupted’, ‘having malicious rumours spread behind your back’, ‘being unduly criticized’, and ‘accusations’, nearly 15 per cent or more of the respondents reported experiencing these bullying behaviours ‘occasionally’. It is important to note that 5 per cent or more of the respondents reported experiencing ‘very often’ the bullying behaviours of ‘lies about you told to others’ and ‘having malicious rumours spread behind your back’ (D’Cruz and Rayner 2010).

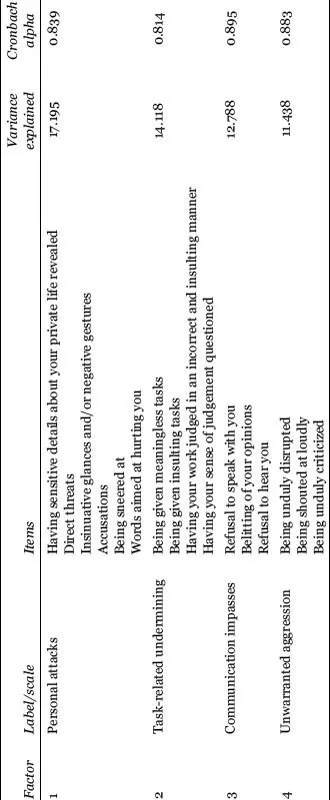

Confirmatory, principal component analysis with varimax rotation using Kaiser normalization yielded four factors that accounted for 16 items (D’Cruz and Rayner 2010). The four factors which explained 55.5 per cent of the total variance and had Cronbach alpha scores of 0.814 and above (Table 1.5) included personal attacks, task-related undermining, communication impasses, and unwarranted aggression. These four categories of bullying behaviours reflect clusters similar to those found in various European countries (see Zapf et al. [2011] for a review of factor analyses of bullying categories).

Converting the factor items into scales, D’Cruz and Rayner (2010) report no significant correlations between any of the scales and gender, age, educational level, years of work experience, income, position in employer organization, geographical location, ownership of employer organization, nature of employer organization, and nature of work, using r2 = 0.2 as the bottom limit.

TABLE 1.4

Item-wise Analysis of Responses to the Work Harassment Scale

Source: D’Cruz and Rayner (2010: 12–13).

TABLE 1.5

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Source: D’Cruz and Rayner (2010: 13–14).

Discussion

That interpersonal bullying is present in Indian workplaces is not surprising. India’s socio-cultural dynamics underscore that workplace bullying is possible and could even coexist with sexual/gender, sexuality-related, caste-based, religious, and illness- and disability-linked discrimination and harassment.

Indian society is known for its collectivist, humanist and spiritual orientations (Hofstede 1980; Kakar and Kakar 2007; Sinha and Tripathi 2002; Verma 2004) emphasizing transpersonal growth (Verma 2004), resulting in images of a people who value tolerance, sensitivity and connectedness, and who emphasize the metaphysical and the community. Yet, these labels mask a web of complexity (Beteille 2006; Kakar and Kakar 2007; Sinha and Tripathi 2002).

Individualism and collectivism coexist at both the individual and the societal levels (Sinha and Tripathi 2002; Verma 2004). According to Sinha and Tripathi (2002) and Tripathi (2002), these orientations operate as figure and ground, depending on the demands of the situation. In Indian society, emphasis is placed on the realization of the self, though one also has to transcend this in the interests of the larger society. Depending on the context and the characteristics of the person, the boundaries of the self can get extended so as to reduce the salience of the group and individualism prevails. In another situation, the same individual may exhibit a collectivist orientation where the self gets completely submerged within the boundaries of the group.

Indian society is relational with social affiliations providing belongingness and support. Yet, this relational orientation in the Indian context is characterized by personalized and identity-based interactions where social networking and exchanges as well as ingroup (apna)–outgroup (paraya) distinctions play a major role (Kakar and Kakar 2007; J. B. P. Sinha 1982, 1994a; Verma 2004). Ethnicity, kinship, caste, class, occupation, region, and religion influence these processes, with implications for the enactment of social life (Agnes 2002; Beteille 2006; Hutnik 2004; Fernandes 2004; Kakar and Kakar 2007; Robinson 2004; Sridharan 2004; Sundaram and Tendulkar 2003; Xaxa 2001). Not surprisingly, favouritism and nepotism thrive, with ingroup members receiving privileges and outgroup members being discriminated against. On the one hand, people are loathe to relinquish their identity-based affiliations because of the accompanying advantages. On the other, interpersonal and intergroup conflict are the natural outcomes (Agnes 2002; Fernandes 2004; Hutnik 2004; J. B. P. Sinha 1982, 1994a; Sridharan 2004; Verma 2004). It is relevant to point out that people have multiple identities which intersect with each other and belong to multiple ingroups (Agnes 2002; Purkayastha et al. 2003; Sundaram and Tendulkar 2003), each of which has its own salience that could vary with situations (Verma 2004).

Interpersonal interactions are also determined by high power distance (Hofstede 1980; J. B. P. Sinha 1994a; Verma 2004), stemming from various hierarchical systems including age, ordinal position, gender, caste, occupation, class, authority, and ethnicity, all of which are integral to the social structure (Bandyopadhyay 2000; Beteille 2006; Fernandes 2004; Kakar and Kakar 2007; Rege 2003; Sridharan 2004; Sundaram and Tendulkar 2003; Xaxa 2001). Through the ascribed status that is conferred via the various hierarchical systems, power is distributed such that those higher up in the hierarchy enjoy power over those below (J. B. P. Sinha 1982, 1994a). The need for and the experience of power, which are greatly valued in Indian society, are played out through the process of giving. While, on the one hand, giving is linked with spiritualism, on the other, it adds complexity to the fabric of interpersonal relationships. The Indian social network, developed around mutual obligations manifested as charitable dominance and benevolent and nurturant patronage from the side of the superior-giver and as respectful and graceful deference, loyalty and indebtedness from the side of the subordinate-receiver, operates as the expression of power. Paternalism is cle...