![]()

Chapter 1

INTRODUCTION

THE ISSUE

The health of a population, if it is to be maintained in a ‘sustainable state’ (King, 1990), requires the continued support of clean air, safe water, adequate food, tolerable temperature, stable climate, protection from solar ultraviolet radiation, and high levels of biodiversity. Socio-economic changes and health interventions have improved public health in recent decades, although there are still many disparities in fulfilled health potential on the global level and amenable morbidity and premature mortality continue to exist (World Health Organisation (WHO), 1995a). However, as a counter-effect of economic development, health impairments have started to occur as the result of deteriorating global environmental conditions.

Global environmental change is a general umbrella term for a whole range of mutually dependent global environmental problems attributable to human activities. They include acidification, eutrophication, deforestation, land degradation and desertification, loss of biodiversity and depletion of fresh water supplies. Major global environmental changes that can be expected to have a significant health effect include climate change and ozone depletion (McMichael et al., 1996). Human-induced climate change and stratospheric ozone depletion are now threatening the sustainability of human development on the planet, because they threaten the ecological support systems on which human life depends (McMichael, 1993), as well as human health and wellbeing, the continuing improvement of which should be the very goal of the development process itself. King (1990) has pointed to the widespread agreement that numerous developing countries are ‘demographically trapped’, in that communities have exceeded or are projected to exceed the carrying capacity of their local ecosystems, their ability to migrate, and the ability of the economies to produce goods and services in exchange for food and necessities. These gross failures in sustainable development are marked by the health patterns associated with infectious diseases, malnutrition and starvation (partly relieved by food aid). Climate change and depletion of the ozone layer could inflict severe additional stress on such already overburdened ecosystems.

Climate Change and Ozone Depletion

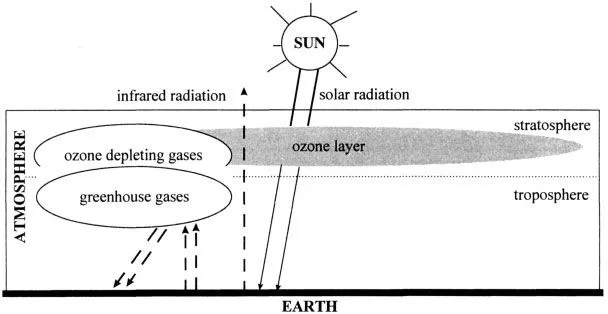

Greenhouse gases allow incoming solar radiation to pass through the atmosphere but trap the re-radiated long-wave radiation from the Earth’s surface (see Figure 1.1). Since the Industrial Revolution, human activities have increased the atmospheric concentrations of the greenhouse gases, leading to the enhanced greenhouse effect. The main anthropogenic greenhouse gases are carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O), and chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs).

Figure 1.1: Simplified Diagram Illustrating the Greenhouse Effect and Stratospheric Ozone Depletion

The concentration of CO2 has increased by around 25 per cent primarily due to emissions from fossil fuel burning and deforestation. CH4 has more than doubled in concentration since 1750. Sources of CH4 are less certain than those of CO2 but include rice paddies, animal and domestic waste, coalmining and venting of natural gas. The atmospheric concentration of N2O has also been growing since the mid-18th century, and its sources include nylon production, three-way catalytic converters in cars, and, possibly, agriculture. CFCs, used in refrigerators, air conditioners, and foam insulation, are not only involved in greenhouse warming in the troposphere, but also in the depletion of the ozone layer in the stratosphere. Recently, evidence has accumulated that sulphate aerosols (products of sulphur dioxide) may dissipate solar radiation and thus prevent it from reaching the Earth’s surface, thereby masking the enhanced greenhouse effect over some parts of the Earth (Charlson & Wigley, 1994; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), 1996). Changes in the concentration of greenhouse gases and aerosols, taken together, are projected to lead to regional and global changes in climate and climate-related parameters such as temperature and precipitation. Although the reliability of regional projections is still poor, and the degree to which climate variability may change is uncertain, climate models project an increase in global mean surface temperature of about 1°C–3.5°C by 2100 (IPCC, 1996).

Ozone (O3) is an atmospheric trace gas, 90 per cent of which is distributed in the stratosphere, mostly between altitudes of 15–25 km. The destruction of the stratospheric ozone layer is largely attributed to reactive chlorine, liberated from mainly CFCs under specific meteorological conditions in the stratosphere (sunlight and stratospheric cloud formation). In the stratosphere ozone acts like a protective shield, preventing much of the sun’s ultraviolet radiation (UV), especially UV with shorter wavelengths, from reaching the Earth. Over the past few decades, stratospheric ozone concentrations have fallen globally, especially during winter and springtime at higher latitudes, and most markedly over the Antarctic. Over approximately the period 1980–1990 ozone depletion at northern latitudes of 30–60°N has been 6 per cent during winter and spring, and 3 per cent during summer and autumn. In the southern hemispheric, cumulative ozone depletion has amounted to 5 per cent per decade since 1980 (United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), 1994). As a result of this decrease in the thickness of the ozone layer, more UV-B radiation is expected to reach the earth.

The problems of climate change and ozone depletion are interrelated, not only by virtue of their common sources, but also as a consequence of the numerous interrelations between them. Depletion of ozone in the lower stratosphere could cause a reduction in the radiative forcing, which could offset a fraction of the global warming attributed to the increases in the abundance of greenhouse gases (Ramaswamy et al., 1992; World Meteorological Organisation (WMO), 1992). The increases of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere and the resulting tropospheric warming and stratospheric cooling will affect the ozone concentrations in the stratosphere: the decrease in the stratospheric temperature will slow down the rate of ozone destruction induced by chemical reactions. An indirect impact of rises in UV radiation associated with global warming is the impairment of the primary production of phytoplankton, which will limit the oceans’ role in acting as a sink for CO2. This will lead to an increase in atmospheric CO2 concentrations (den Elzen, 1993).

Nevertheless, the essential difference between greenhouse accumulation and stratospheric ozone depletion should be borne in mind. Greenhouse gas accumulation increases the effect of radiative forcing on climate, while stratospheric ozone depletion by chlorine radicals leads to increased UV radiation at ground level. These two distinct phenomena are thus members of a wider-ranging family of global atmospheric changes.

Health Impacts

Increased levels of UV radiation due to ozone depletion may have serious consequences for living organisms. Adverse impacts of UV-B have been reported on terrestrial plant growth and photosynthesis. Increased UV-B has also been shown to have a negative influence on aquatic organisms, especially small ones such as phytoplankton, zooplankton, larval crabs and shrimps, and juvenile fish. Since many of these organisms are at the base of the marine food chain, increased UV-B may seriously affect aquatic ecosystems (for more details on these effects see, e.g., UNEP, 1994; WHO, 1994). Furthermore, increased UV-B radiation affects tropospheric air quality and may cause damage to materials such as wood, plastics and rubber.

Climate changes are also likely to be associated with a multitude of effects: climate change will shift the composition and geographic distribution of many ecosystems (e.g. forests, deserts, coastal systems) as individual species respond to changed climatic conditions, with likely reductions in biological diversity; agricultural yields may also be affected. Climate changes will lead to an intensification of the global hydrological cycle and may have impacts on regional water resources. Additionally, climate change and the resulting sea-level rise can have a number of negative effects on energy, industry and transportation infrastructure, human settlements, and tourism (for more details see IPCC, 1996).

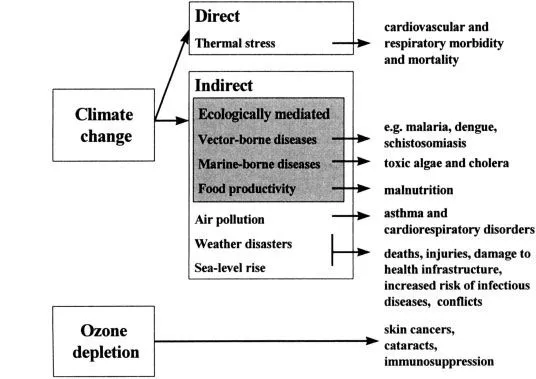

Only recently has attention been paid to the possible consequences of these global atmospheric changes for human health (e.g. WHO, 1990; Haines & Fuchs, 1991; Doll, 1992; McMichael, 1993, 1996; McMichael et al., 1996). Figure 1.2 summarises some of the important potential effects of climate change and ozone depletion upon human population health. Broadly speaking, the various potential health effects of global climate change upon human health can be divided into direct and indirect effects, according to whether they occur predominantly via the impacts of climate variables upon human biology, or are mediated by climate-induced changes in other biological and biogeochemical systems.

In healthy individuals, an efficient regulatory heat system enables the body to cope effectively with thermal stress. Temperatures exceeding comfortable limits, both in the cold and warm range, substantially increase the risk of (predominantly cardiopulmonary) illness and deaths. Directly, an increase in mean summer and winter temperatures would mean a shift of these thermal-related diseases and deaths. An increased frequency or severity of heatwaves will also have a strong impact on these diseases. If extreme weather events (droughts, floods, storms, etc.) were to occur more frequently, increases in rates of deaths, injury, infectious disease and psychological disorder would result.

One of the major indirect impacts of global climate change upon human health could occur via effects upon cereal crop production. Cereal grains account for around two-thirds of all foodstuffs consumed by humans. These impacts would occur via the effects of variations in temperature and moisture upon germination, growth, and photosynthesis, as well as via indirect effects upon plant diseases, predator-pest relationships, and supplies of irrigation water. Although matters are still uncertain, it is likely that tropical regions will be adversely affected (Rosenzweig et al., 1993), and, in such increasingly populous and often poor countries, any apparent decline in agricultural productivity during the next century could have significant public health consequences. A further important indirect effect on human health may well prove to be a change in the transmission of vector-borne diseases (Patz et al., 1996). Temperature and precipitation changes might influence the behaviour and geographical distribution of vectors, and thus change the incidence of vector-borne diseases, which are major causes of morbidity and mortality in most tropical countries. Increases in non-vector-borne infectious diseases, such as cholera, salmonellosis, and other food- and water-related infectious diseases could also occur, particularly in (sub)tropical regions, due to climatic impacts on water distribution, temperature and the proliferation of micro-organisms.

Figure 1.2: Health Impacts due to Climatic Changes and Ozone Layer Depletion (Source: Patz & Balbus (1996))

Table 1.1: Summary of Known Effects and Uncertainties Regarding Health Impacts of Climate Change and Ozone Depletion

| Health effect | Known effects | Uncertainties |

Thermal stress | * Mortality (especially cardiopulmonary) increases with cold and warm temperatures * Older age groups and people with underlying organic diseases are particularly vulnerable * Mortality increases sharply during heatwaves | * The balance between cold- and heat-related mortality changes * The extent to which heatwaves take their toll among terminal patients * The role of acclimatisation of people to warmer climates |

Vector-borne diseases | * Climate conditions (particularly temperature) necessaiy for some vectors to thrive and for the micro-organisms to multiply within the vectors are relatively well known | * Indirect effects of climate change on vector-borne diseases, such as changes in vegetation, agriculture, sea-level rise, migration, etc. * Effects of socio-economic development, resistance development, etc. |

Water-/food-borne diseases | * Survival of disease organisms (and insects which may spread them) is related to temperature * Water-borne diseases most likely to occur in communities with poor water supply and sanitation * Climate conditions affect water availability * Increased rainfall affects transport of disease organisms | * For many organisms the exact ambient conditions in which they survive and are transmitted are not known * Interaction with malnutrition is not well understood |

Food production | * Temperature, precipitation, solar radiation and CO2 are important for crop production * Crop failure may lead to malnutrition * Undernourishment may increase susceptibility to infectious diseases | * Variations in crop yield due to climate change are poorly understood * Effects of climate on weeds, insects and plant diseases are not well known * Interaction between nutritional status and diseases is poorly understood |

Skin cancer | * Skin cancer incidence is related to UV exposure * Ageing increases the risk of skin cancer | * Dose-response relationship between UV radiation and skin cancer, especially basal cell carcinoma and melanoma skin cancer, is not completely clear |

Cataracts | * UV radiation damages the eye, more particularly the lens * Different types of cataracts will react differently to changes in UV radiation * Aetiology of cataracts is associated with age, diabetes, malnutrition, heavy smoking, hypertension, renal failure, high alcohol consumption, and excessive heat | * Dose-... |