![]()

1 Athens after the end of the Peloponnesian war

Athens emerged from the Peloponnesian war defeated and humiliated. She had lost her foreign possessions, surrendered her fleet, destroyed her Long Walls. She was dependent for her corn supplies on the goodwill of her conqueror, Lysander. It is therefore not surprising that the opponents of democracy, who had been waiting ever since 410 to take their revenge, promptly seized the opportunity offered them.

The political crisis: the oligarchic revolution and the restoration of democracy

The chronology of the events which then took place is not very certain, for our sources sometimes contradict one another. From Xenophon’s account it would seem that the establishment of the regime of the Thirty preceded the taking of Samos by Lysander, whereas Lysias in the speech Against Eratosthenes seems to suggest that the oligarchs waited to act until the Spartan leader’s return.1 In any case he was present at the Assembly at which the government of the polis was handed over to the Thirty. Xenophon merely describes the event as a decision emanating from the people. Lysias, on the contrary, reports strong opposition:

Theramenes now rose and ordered the city to be put into the hands of thirty individuals, and the constitution in preparation by Drakon-tides to be adopted. Even as things were, there was a violent outburst in refusal. It was realised that the issue of the meeting was slavery or freedom. Theramenes, as members of the jury can themselves testify, declared that he cared nothing for this outburst, as he knew that a large number of Athenians were in favour of the same measures as himself, and he was voicing the decisions approved by Sparta and Lysander. After him Lysander spoke, and among other statements pronounced that he held Athens under penalty for failing to carry out the terms of the truce, and that the question would not be one of her constitution, but of her continued existence. True and loyal members of the Assembly realised the degree to which the position had been prepared and compulsion laid upon them, and either stood still in silence or left, with their conscience clear at any rate of having voted the ruin of Athens(Against Eratosthenes, 73–5).

This implies that a small minority of those present had been solely responsible for deciding the city’s fate. We may, of course, wonder whether Lysias, prosecuting one of the Thirty some years after the event, did not find it advantageous to flatter the judges by absolving them of responsibility and praising their resistance, however passive. In point of fact, if we are to believe another of Lysias’ speeches, Against Agoratos, the leading democrats had already been arrested or had gone into exile on the conclusion of the peace treaty. However that may be, thirty citizens were thus appointed whose mission was to draw up a new constitution, or rather a constitution conforming to the patrios politeia, the ancestral constitution.2 The only information we possess on the manner in which the Thirty were appointed is provided by Lysias, in the same speech Against Eratosthenes (76): ten of them were appointed by Theramenes, who does indeed seem, in collusion with Lysander, to have instigated the whole affair; ten more by the ephors, and the last ten elected by what remained of the Assembly. These thirty evidently included Theramenes, Kritias, Plato’s cousin, who had had a stormy political career during the closing years of the Peloponnesian war, Drakontides, Peison and other less-known figures, among them Lysias’ future adversary, Eratosthenes. Their first concern was to appoint a Council composed of their supporters and to make sure of controlling the principal magistrates’ colleges. Next they brought to trial before the Council a certain number of citizens who had previously been arrested on a charge of plotting against the safety of the state, but in actual fact, if we are to believe the author of the speech Against Agoratos (15 ff.), for having tried to oppose the peace treaty which reduced Athens to unconditional surrender. We may assume that these summary sentences, imposed under illegal conditions, aroused some dissatisfaction, and that in order to have their hands free the Thirty then asked Sparta to send a Lacedaemonian garrison. Xeno-phon tells us:

Once they had got the garrison, they paid court to Callibios in every way, in order that he might approve of everything they did, and as he detailed guardsmen to go with them, they arrested the people whom they wished to reach—not now the ‘scoundrels’ and persons of little account, but from this time forth the men who, they thought, were least likely to submit to being ignored, and who, if they undertook to offer any opposition, would obtain supporters in the greatest numbers (Hellenica, XI, iii, 14).

In the speech Against Eratosthenes Lysias gives us an example of this kind of summary arrest:

At a meeting of the Thirty, Theognis and Peison made a statement that some of the metics were disaffected, and they saw this as an excellent pretext for action which would be punitive in appearance, but lucrative in reality. They had no difficulty in persuading their fellows, to whom killing was nothing, while money was of great importance. They therefore decided to arrest ten people, including two of the poorer class, to enable them to claim that their object was not money, but the good of others, as in any other respectable enterprise (Against Eratosthenes, 6–7).

The Thirty therefore shared out the task among themselves, and it was Peison and Theognis who entered the house where Lysias was dwelling. While Theognis went into the factory which Lysias had inherited from his father, Kephalos, to make an inventory of the slaves and of the objects there, Lysias succeeded in ‘buying off’ Peison, who took him to the house of a mutual friend, whence Lysias was able to escape through an unguarded door and reach the port, where he succeeded in embarking for Megara. Meanwhile another of the Thirty, Eratosthenes, had seized Polemarchos, brother of Lysias, and taken him to prison, where he was made to drink hemlock. The Thirty were now free to seize the fortune of the two brothers, their furniture and jewels and clothes and the hundred and twenty slaves who were working in the factory.

There can be no doubt that such scenes took place repeatedly, spreading terror in the city among all those whose wealth or whose opinions made them suspect to the masters of the hour. According to Xenophon and Aristotle,3 it was these arbitrary measures which brought about the rupture between Theramenes, who had hitherto been seen as the leader of the Thirty, and Kritias. This tradition, favourable to Theramenes, which we find expressed by Xenophon and by Aristotle in particular, must have arisen immediately after the restoration of the democracy, and it is interesting to note that Lysias, in the speech Against Eratosthenes, attacks those who tried to make Theramenes out as a victim:

If the friends of Theramenes had perished with him, unless they had adopted the opposite course to his, it would have been no more than they deserved. Instead of this we find a defence made of him, and attempts by his associates to take credit as the authors of numerous benefits instead of untold detriment (64).

And Lysias reminds his hearers that Theramenes had been one of the Four Hundred, and that after Aigospotamoi it was he who, by dragging out negotiations, had helped to deliver Athens into the hands of Lysander. In the eyes of the democrats, Theramenes was the accomplice of the oligarchs. For a whole section of Athenian opinion, however, he represented a moderate trend, as foreign to the demagogy of the last years of the war as to the extreme oligarchy of which Kritias was the representative. And the profession of faith attributed to him by Xenophon in the Hellenica, during his famous debate with Kritias, is a fair summary of the ‘programme’ of these moderates:

But I, Kritias, am forever at war with the men who do not think there could be a good democracy until the slaves and those who would sell the state for lack of a shilling should share in the government, and on the other hand I am forever an enemy to those who do not think that a good oligarchy could be established until they should bring the state to the point of being ruled absolutely by a few. But to direct the government in company with those who have the means to be of service, whether with horses or with shields,—this plan I regarded as best in former days and I do not change my opinion now (Hellenica, II, iii, 48).

In point of fact, even if we are to accept as authentic the opposition between the extremist and the moderate trends of the oligarchic ‘party’, it was clearly in the interest of Theramenes’ friends, so soon after the restoration of the democracy, to stress that opposition, distinguishing themselves from Kritias and his accomplices. None the less the rupture between Kritias and Theramenes, and the death sentence passed on the latter, under illegal conditions, reflected divergences within the oligarchic class, divergences which were to contribute to the weakening of the regime of the Thirty.

For while the city endured a reign of terror which entailed many arrests, banishments and confiscations of goods, resistance was beginning to be organized. It was probably soon after the arrest and execution of Theramenes that Thrasyboulos, who had taken refuge in Thebes, succeeded with a small band of supporters in seizing the citadel of Phyle. This first success was to have important consequences. Supporters poured in from all parts of Attica, and soon Thrasyboulos was strong enough to launch an attack on the horsemen who had been sent by Kritias into the frontier region between Boiotia and Attica. The result of this military success was not only to strengthen the position of the democrats but, furthermore, to alarm the Thirty, who left Athens and took refuge at Eleusis, having first put to death all those whom they considered suspect, both at Eleusis and at Salamis.

The gulf grew even wider between the oligarchic extremists and the townspeople, most of whom were inscribed on the list of the Three Thousand, and who had begun to envisage a rapprochement with the people of Phyle. Soon afterwards, Thrasyboulos, the number of whose supporters had constantly increased, took possession of the Piraeus. The Thirty made a last effort to recapture the port, but they were defeated at Munychia in a battle in which Kritias lost his life. Confusion reigned among the oligarchs. They were divided as to the course to be followed. Some, more clear-sighted, realizing that it would not be easy to recapture the port, were in favour of reconciliation with Thrasyboulos; others ‘urged strenuously that they ought not to yield to the men of the Piraeus’ (Hellenicay II, iv, 23). Finally the people of the city, dismissing the Thirty to Eleusis for good, appointed ten magistrates, among whom were some men who might be expected to work for reconciliation with the democrats. At all events, this is what Lysias implies in the speech Against Eratosthenes. But, the orator adds, ‘as soon as they assumed power themselves they gave rise to still more violent dissension in Athens, against the Piraeus. … On assuming control of the government and the city, they made common cause against the Thirty who had been the cause, and the people’s party who had been the victims, of all the trouble’ (57).

In fact, the war began again more fiercely than ever between the two sides. On the Piraeus, Thrasyboulos mobilized forces of every sort. It is interesting to note that, in view of the political character of the struggle, he did not merely recruit men of every social condition to fight side by side, he even appealed to foreigners, promising them isoteleia if they would engage in battle by the citizens’ side. We have here an even clearer indication than in 411 B.C. that political oppositions did in fact conceal social antagonisms, and that the presence of rich men in Thrasyboulos’ party did not invalidate the popular character of his army, in which light infantry, armed with hastily improvised bucklers, replaced the heavy infantry of the hoplites, and which included few horsemen. The townspeople took fright on seeing these developments, and appealed to Lysander to intervene without delay. He therefore prepared to concentrate his forces at Eleusis and to block the port so as to prevent supplies from reaching the Piraeus. Xenophon’s account gives one the impression that without the intervention of the Spartan king, Pausanias, who, jealous of Lysander, decided to take him by surprise and to negotiate peace between the two parties, the men of Piraeus would have been doomed to defeat. Xenophon himself admits, however, that Thrasyboulos succeeded in repulsing the assault made jointly by Pausanias’ army and Lysander’s mercenaries against the Piraeus, and that this victory precipitated negotiations. And it was indeed as victors that the men of Piraeus returned to Athens and climbed the Acropolis ‘in arms’ to sacrifice to the goddess. The only result of Pausanias’ good offices was the undertaking made by the democrats not to seek vengeance on their adversaries except in the case of those who had compromised themselves with the oligarchy. The speech ascribed by Xenophon to Thrasyboulos at the end of Book III of the Hellenic a is clear evidence of the political character of the victory won by the democrats. The victor’s words are first addressed to the townspeople, challenging the superiority on which they prided themselves in order to claim an exclusive right to political power:

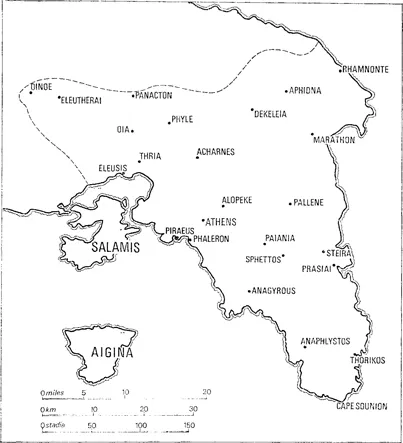

Attica

Are you more just ? But the commons, though poorer than you, never did you any wrong for the sake of money; while you, though richer than any of them, have done many disgraceful things for the sake of gain. But since you can lay no claim to justice, consider then whether it is courage that you have a right to pride yourselves upon. And what better test could there be of this than the way we made war upon one another? Well then, would you say that you are superior in intelligence, you who, having a wall, arms, money, and the Peloponnesians as allies, have been worsted by men who had none of these? (II, iv, 40–1).

Then Thrasyboulos, addressing his comrades-in-arms, urged them to respect their vows and indulge in no revolutionary agitation, but on the contrary to return to the ancient laws of the polis. Are we to suppose that, under cover of the conflict, certain men were aiming at something more than the mere restoration of democracy ? It is almost impossible to answer this question, since no other source refers to any sort of disturbance. May we assume that certain exiles, on their return to Athens, wished to dispossess their adversaries of the goods these had acquired more or less justly, and to proceed to large-scale confiscations, even to a redistribution of the land, as was being done and would continue to be done elsewhere? The only ‘illegal’ measures seem to have been those proposed by Thrasyboulos in favour of the foreigners and slaves who had fought by his side, on whom he wanted to confer the right of citizenship. A graphe para-nomon was brought against him by Archinos, and the proposal was dropped.4

We may wonder why the Athenian demos consented so readily to be cheated of the material advantages of victory, and why, during the years that followed, the city-state was in fact ruled by the most moderate members of the Piraeus party, such as Archinos and Anytos, in conjunction with the townspeople. S...