![]()

An introduction to wine in New Zealand

Peter J. Howland

Introduction

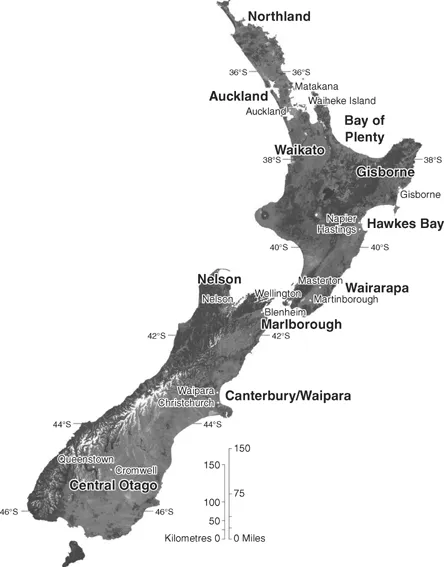

New Zealand – also known as Aotearoa (translated as ‘land of the long white cloud’) – sits in the south-western Pacific Ocean between latitudes 34°S and 47°S (see Figure 1.1) and has a north-south span of 1,600 kilometres or 994 miles. Consisting of two main islands that are narrow (the maximum width is 400 kilometres or 248 miles) and with 14,000 kilometres or 8,700 miles of coastline, New Zealand has a temperate maritime climate with cooler summers and milder winters than comparable latitudes in the northern hemisphere (see Figure 1.2). New Zealand was first settled by Polynesian explorers and the ancestors of the indigenous Māori in the thirteenth century and then five centuries later by predominantly British settlers. Today New Zealand has a comparatively small population of 4.47 million, some 60 million sheep and a recorded history of winemaking of less than 200 years.

Responsible for just 0.7 per cent of global production in 2010 (International Organisation of Vine and Wine 2012; New Zealand Winegrowers 2012), New Zealand-produced wines have garnered international attention since the mid-1980s. Some, such as Marlborough Sauvignon Blanc – the ‘pungent, exuberant, intense … explosive varietal that awoke the world to New Zealand wine’ (www.nzwine.com/wine-styles/sauvignon-blanc, accessed 12 February 2013) – have, at times, dominated varietal price and sale volumes in pivotal markets in Britain and Australia (see Chapter 6). Noted for slow-ripened, cool climate wines that are fruit-driven, intense and with fresh acidity, the industry has experienced significant growth in grape-growers and wineries, plantings and the volume of wine produced and exported in the past few decades (see Chapter 2).

The wine industry in New Zealand is currently dominated by Sauvignon Blanc, which accounted for 17,297 hectares (51.8 per cent) of 33,400 hectares of producing vineyard nationwide and for 181,121 tonnes (67.3 per cent) of 269,000 tonnes produced (New Zealand Winegrowers 2012: 20–21). The industry is similarly dominated by large, industrialized, shareholder-led and transnational producers, the two largest being Constellation (owners of Corona, Robert Mondavi Napa Valley, etc.) who own the Kim Crawford, Nobilo, Selak, Drylands and Monkey Bay wine brands in New Zealand and Pernod Ricard (owners of Beefeater Gin, Mumm Champagne, etc.) who own 10 local wine brands including Brancott Estate (formerly Montana), Stoneleigh, Church Road, Deutz Marlborough and Longridge. Constellation and Pernod Ricard are responsible for 70 per cent of New Zealand-produced wine (Stewart 2010: 376). In 2012 the largest wine producing companies in New Zealand (with annual sales of NZ$20m+) sold 515,741 cases or 71 per cent of the total wine produced (726,446 cases), while companies with annual sales between NZ$10m-$20m sold 134,602 cases or 18.5 per cent. By comparison the smallest categories of companies recording between NZ$0 and NZ$10m in annual sales sold only 76,103 cases or 10.5 percent (Deloitte 2012:8). In the same year, however, the smallest wineries (Category 1, that produce less than 200,000 litres annually) dominated numerically at 622 or 88.5 per cent of all registered wineries. Category 2 wineries (between 200,000 and four million litres annually) numbered 71 or 10.1 per cent, while the Category 3 wineries (four million+ litres annually) numbered only 10 or 1.4 per cent (New Zealand Winegrowers 2012: 19).

Figure 1.1 Map of New Zealand wine regions (source: New Zealand Winegrowers).

Figure 1.2 Sileni Estate, Hawke’s Bay – the Pacific Ocean in the background is indicative of New Zealand’s maritime climate (source: Seleni Estates Ltd and NZW).

Although the wine industry can clearly be framed a number of different ways, New Zealand is nevertheless habitually promoted as a nation of ‘lifestyle wineries’ – that is boutique, family-run, artisan wineries dedicated to the sensitive mapping and articulation of local terroir in the pursuit of high quality, classical and yet vernacular wines produced from Vitis vinifera grapes – most notably Sauvignon Blanc, Pinot Noir, Chardonnay and Pinot Gris (www.nzwine.com, accessed 12 February 2013). However, the wine industry is a complex assemblage of sometimes competing, sometimes complementary, players, motivations and forces (see Chapters 2, 6, 10). These include large-scale, industrial producers, bulk wine exporters (that account for 35 per cent of exported wine – New Zealand Winegrowers 2012: 2), passionate artisans, high volume/low price and small volume/high price retailers, wine connoisseurs and reviewers, and a range of appreciative, casual and indifferent drinkers (Clayton and Stevens 2007; Spratt and Feldman 2012; Stewart 2010). This should be expected of any market-based, capitalist enterprise and especially where the motivation to profitably produce either primary (e.g. grapes or grape-juice) or value-added (e.g. bottled wine) commodities is a constant.

This dominant (and in many ways, free-floating) discourse additionally proclaims that New Zealand-produced wines are fresh, intense, fruit-driven, consistently good-quality and are made by passionate winemakers who adroitly deploy a combination of New World innovation and science (e.g. temperature controlled fermentation) and time-proven Old World techniques (e.g. French oak ageing). This discourse has characterized both the aspirational and exemplar promotions of New Zealand Winegrowers (NZW)1 and its various historic incarnations since the 1980s to the present day – the period in which the wine industry in New Zealand radically shifted away from adulterated, fortified and/or light, sweet wines such as Müller Thurgau (which at the end of the 1970s accounted for 40 per cent of national plantings – Stewart 2010: 305), to making predominantly French-orientated Vitis vinifera wines.

It is also largely the time period covered by the contributors to Social, Cultural and Economic Impacts of Wine in New Zealand who, drawing from a range of academic disciplines – anthropology, architecture, development studies, economics, geography, management and marketing, sociology – provide wide-ranging analyses across the interdependent fields of production, promotion and consumption. These three fields structure the book, together with specific ‘place studies’ of Waiheke Island (Auckland, upper North Island), Martinborough (Wairarapa, lower North Island) and Waipara (Canterbury, mid South Island). A brief outline of the contributors’ differing perspectives is provided in the introductions to each section. The perspectives offered are, however, by no means exhaustive. For example, gendered (and aged) divisions of labour, knowledge and authority on vineyards or in wine consumption; the mutually informative roles of art and science in winemaking; the varied machinations of wine shows, critics and reviews; the impact of economic investments on local communities, employees and vineyard owners; the aesthetics of wine consumption – promotional, collective, individual; the awareness and effect of various legislative regimes in production and consumption; and so on, are mostly outside the volume’s scope, as is the highly informative, emerging research comparing wine-making in New Zealand with that undertaken elsewhere (e.g. Mitchell et al. 2012; Murray and Overton 2011).

My purpose in this introduction is to provide some background to approaching these contributions, first in terms of a brief historical outline of wine production to the 1980s when the ‘modern era’ arguably began, and second, via an equally selective overview of the contemporary wine industry in New Zealand.

The first vines

The history of wine in New Zealand is a ferment of complementary and contradictory motivations, aspirations and consequences, most notably in those capacities frequently assigned to wine in the name of Christianity, civilized society, profitable production and market trade, and the artisanal refinements of fine wine. This is as might be expected of a Tate Settler Society’ where European colonization (chiefly from the 1840s onward) was typically a calculated ‘business proposition’ (McAloon 2002: 52), responsive primarily to the increasingly global forces of industrialized capitalism, intensive agriculture and international commodity trade (Belich 1996; Grey 1994).

It is also expected in regard to historical developments in wine in nineteenth century Europe that were, in part, transported to New Zealand. In the late seventeenth century, winemaking in Europe for religious purposes (sacramental and community), for subsistence consumption by peasant farmers and for market trade in bulk and regionally blended wines, was supplemented by the production of named, vineyard-specific and cork-bottled wines (Johnson 1998 [1989]; Unwin 1996 [1991]; see Chapter 11). This development prompted the production of ‘fine wines’ (i.e. vintage and vineyard-specific) that were increasingly sought after by the aristocracy and emerging elites within the mercantile and educated classes. Moreover it culminated in the ‘golden age’ (Fielden 1999: 409) of wine writing in first half of the nineteenth century in Britain and France, and in the modern forms of connoisseurship that persist today.

The first record of grapevine planting in New Zealand – which lacks an indigenous grape species – was on 25 September 1819 by Samuel Marsden, an English-born Anglican cleric, prominent member of the Christian Missionary Society and chief Chaplain to the Government of New South Wales, Australia. Marsden was on his second journey to New Zealand when he wrote of his efforts to establish a mission at Kerikeri, Bay of Islands (240 km north of Auckland – see Figure 1.1): ‘We had a small spot of land cleared and broken up in which I planted about a hundred grape-vines of different kinds brought from Port Jackson [Sydney]. New Zealand promises to be very favourable to the vine’ (quoted in Thorpy 1971: 22). On 12 October 1819 he further noted that: ‘I was much gratified with the progress that had been made…. The vines were many of them in leaf’ (quoted in Thorpy 1971: 22–23).

Marsden, was ‘not averse to alcohol’ (Thorpy 1971: 21) – his inaugural voyage to New Zealand in 1814 included ‘Spirits, 10 gallons; Teneriffe wine, 40 gallons; Port and Sherry, 5 dozen’ (Thorpy 1971; 21) – and he believed ‘that Māori should be taught the civilising pursuits of agriculture and handicrafts before being converted to Christianity’ (Cooper 2002: 12).

In 1817 Marsden sent Charles Gordon, superintendent of agriculture at Parramatta, New South Wales, to the Bay of Islands to oversee the establishment of agriculture in the colony. Marsden wrote: ‘I think vines would do well from the nature of the soil and climates. I shall, from time to time, send over different plants as they may be useful at some future day’ (quoted in Thorpy 1971: 21–22). Gordon spent three years in New Zealand and although no record remains of what he planted, it is possible it included grapevines.

By the time Charles Darwin visited Kerikeri aboard the HMS Beagle in 1835 as part of his round-the-world expedition, he noted that grapes were thriving a few miles inland at Waimate North and were being tended by Māori associated with the mission (Scott 1964; Thorpy 1971). In 1838 another traveller, Joel Polack, noted in New Zealand; being a Narrative of Travels and Adventures that: ‘At present [1838] grapes are largely cultivated to the northward of the River Thames and the Kaipara’ (quoted in Thorpy 1971: 23). The Thames River is in the Waikato, 270km south of the Kaipara Harbour, which is 130km south of Kerikeri.

The first record of wine being made is, however, not until May 1840 when the French explorer Dumont d’Urville noted, while visiting the Waitangi (Bay of Islands) settlement of James Busby, that:

With great pleasure I agreed to taste the product of the vineyard that I had just seen. I was given a light, white wine, very sparkling, and delicious to taste, which I enjoyed very much. I have no doubt that vines will be grown extensively all over the sandy hills of these islands.

(quoted in Stewart 2010: 33; see also Cooper 2002; Scott 1964; Thorpy 1971)

Busby was a Scotsman and, like Marsden, firmly believed in the humanist and civilizing efficacy of viticulture: ‘Wine to him was not just an item of trade or produce from his budding farm, it was also the beverage of Utopia’ (Stewart 2010: 32). In 1823, as a 22-year-old, Busby visited Bordeaux and two years later published A Treatise on the Cultural of the Vine and the Art of Making Wine. Busby was an ‘unusual colonial, absorbed by the supremacy of the British Empire and its Tory inclinations, yet a supporter of the Mediterranean culture of the vine’ (Stewart 2010: 29).

In 1832, Busby was appointed the first British Official Residence of New Zealand and before emigrating he undertook a four-month tour of the European wine regions familiar to his ‘middle-class experience: Sherry, Hock, Claret, Hermitage and Burgundy’ (Stewart 2010: 23). Busby arrived back in London with more than 600 differently classified varieties of grapevine (fruit and winemaking). These were placed in the care of organizations such as Kew Gardens before 362 vine stock were shipped to Sydney, where they were planted in the Botanic Gardens. Although this collection disappeared due to neglect, Busby is widely regarded as the ‘father’ of Australian viticulture.

In June 1833, Busby dispatched the first Vitis vinifera grapevines to Waitangi. These were followed by another 100 in June 1836 and 40 more a month later. There is no record of the varieties sent or planted in a nursery intended to provide foundation stock, although it is likely they were those favoured by Busby in his writings – ‘syras [syrah], marsanne, roussane, chaudeney [chardonnay], pineau noir [pinot noir], cabernet sauvignon, merlot and malbec’ (Stewart 2010: 32).

With the declaration of New Zealand as a British colony in 1840 and the appointment of a Governor, Busby’s position as Resident was disestablished. During the 1840s Busby’s gardens and vineyard at Waitangi were destroyed by occupying British forces fighting the prominent Māori rangatira (chiefs) Te Ruki Kawiti and Hone Heke. The Land Wars fought between the British and Māori from 1845 to 1872 were aimed at asserting colonial authority and acquiring indigenous lands for settlement. Most settlers possessed modernist attitudes that affirmed an essential ‘malleability of the world’ (Boorstin – quoted in Grey 1994: 16) and possessed profit, market-orientated perspectives that clashed with Māori whose relationship to the land was spiritual, ancestral, kinship- and subsistence-based. Furthermore, colonists were confronted by a physical ‘environment dominated by subtropical rainforest, a dark, virile phenomenon that was as alien to British sensibilities as the surface of Mars’ (Stewart 2010: 42). These factors, combined with the fact that British settlers did not possess a culture of peasant or vin ordinaire (everyday) wine production and consumption, m...