![]()

1 Metic Women, Citizenship, and Marriage in Athenian Law

The legal status of metic women was not static, but changed repeatedly over the course of the fifth century until it stabilized somewhat in the fourth. This chapter examines the ebbs and flows of metic women’s legal status from the origins of metoikia in the early fifth century to the ban on marriage between metic women and citizen men in the early fourth. This chapter provides a framework for the chapters that follow by addressing the status of metics in general, how women’s status within the metic community differed from that of metic men, and how laws regarding marriage and citizenship specifically impacted metic women.

The Origins of Metoikia

Opportunities for metic women and their children in Athens fluctuated greatly over the course of the fifth and fourth centuries in Athens. Although immigrants likely came to the city in small numbers in the sixth and early fifth centuries, it was not until the 460s that they were granted an official status in law. Metoikia is the term used to denote the formal, legal status for resident foreigners in classical Athens. According to Aristophanes of Byzantium (third century CE) it classified foreign residents who had been in the city for longer than a specified time and who were subject to the metic tax (metoikion).1 In the fourth century, the status further required registration of individuals and families with the polemarch, the official charged with maintaining the metic lists and in whose court metics could have disputes heard. Metics in the fourth century were also subject to a series of criminal prosecutions that were unique to them such as the graphê aprostasiou, failure to register and pay the metoikion. The metic, according to Aristotle, was also required to have a citizen prostates to stand for them in the courts.2

Although many scholars have dated the establishment of metoikia to the reforms of Kleisthenes in 508/7 BCE, problems with this view remain. It is based on the new deme structure created by Kleisthenes and on links recognized between metics and demes found in the fourth century. 3 In the fourth century, metics were registered in a deme and are frequently listed as “dwelling in” a deme on records. The evidence is primarily a retrojection of later evidence back onto the Kleisthenic period and lacks any contemporary or near contemporary evidence.

Geoff Bakewell discusses in detail the problems with evidence used to date the institution to the Kleisthenic period, including

IG I

3 1357 (Kerameikos I.388/SEG 22.79), the Themistokles decree (ML 23), and Aristotle

Politics 1275b36-37.

4 The Aristotle passage is decidedly anachronistic and so can be no proof for a late sixth- to early fifth-century institution. Baba has argued concerning

IG I

3 1357

, an inscription on a grave monument for Anaxilas the Naxian, that

metaoikon be read instead of

meteoikon, as it had originally been read.

5 Baba further argues that with this change the term

metaoikon can clearly be understood as the technical term for a resident alien in Athens as early as 510

BCE.

6 The arguments, however, as Bakewell makes clear, are unconvincing and Whitehead's earlier assertion still seems the most plausible interpretation; the word was being used in a non-technical sense to denote not his status upon death, but only his resting place relative to his home on Naxos.

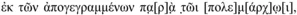

7 Finally, the Themistokles decree does not even mention metics, but "

xenoi living within Athens" (

7) or "those

xenoi registered with the

polemarcb" (

31-32). Scholars have taken the phrase "registered with the

polemarch" to imply a formal institution, although the term

polemarch itself is heavily restored (all but two letters) and the language of

metoikia does not appear at all.

8 At the most, one can suggest that

xenoi who lived in the city were expected to register their names. We do not know if they were registered with a deme, as in the fourth century, or if they simply received permission and informed the

polemarcb that they were residing in the city. There is no evidence at all of a tax or even a formal legal status. Other scholars, therefore, have argued that a formal status for metics in Athens did not evolve until the late 470s or early 460s (or even as late as 451

BCE) and did so only under the increased pressure of immigration to Athens in the years following the Persian Wars. Cynthia Patterson writes:

It seems plausible that the mid-fifth century saw significant development in the main features of the classical status of resident foreigners, such as the requirement of registration with a deme, the guarantee of legal rights or institution of the metoikon. This may have been part of the Periklean legislation, or the result of it, or perhaps in anticipation of it, but in any case, it makes sense in the same context in which we have viewed Perikles’ citizenship law.9

The evidence from inscriptions and other contemporary sources seems to support this view.

The first known reference in the epigraphic evidence to metoikia as a distinctive political status is IG I3 244, which contains laws for ritual observance in the deme of Scambonidae.10 The inscription is dated by D. M. Lewis to around 460 BCE and clearly differentiates between the citizen members of the tribe and a group called metics.11 Almost contemporary with this inscription is Aeschylus’ Suppliants, which has the earliest known usage of the various terms associated with metoikia. According to Bakewell’s arguments (which I address in detail in Chapter 2), the link made in the play between the terminology and the explicit rights allotted metics as part of their status suggests that the concept must have already developed. It is unlikely that Aeschylus invented a new legal category himself. But it is also unlikely that such explicit reference to the mechanics of an institution would have been necessary if metoikia had been established and functioning for four decades previously. It seems most likely that during the 460s, the formal status of metoikia emerged out of legislative actions addressing legal status for allies and citizens in the archê,12 whereas the Citizenship Law of 451 BCE was one of the earliest refinements of the status once it had been established for a period of time and its implications more developed.13

The Periklean Citizenship Law of 451 BCE

In 451 BCE, the Athenian assembly passed a law that, as far as we know, stated simply that all Athenian citizens must be born of two Athenian citizen parents. It is unclear what motivated the law; in fact, there must have been multiple motivations. Cynthia Patterson has pointed to an increase in immigration to Athens in the years between 480–451 BCE and the increased attempts by the Athenians to distinguish themselves from other Greeks, a necessity given the development of their archê and of laws that set different penalties and jurisdiction for violations involving Athenian citizens.14 Other scholars have considered it to be an anti-aristocratic law aimed at clamping down on dynastic marriages among the Athenian elite to foreign kings and aristocrats or as targeting specific political families in Athens.15 The memory of Peisistratos and his Eretrian-financed takeover of Athens and of his son Hippias’ appearance with the Persian army at Marathon perhaps lingered still in the public psyche.

There may also have been a more populist impulse behind the law. Craftsmen and merchants from the Aegean and beyond poured into Athens to work as ship-builders, or to take advantage of Athens’ harbors and increased Mediterranean trade, or to work on the various public building programs that were launched in the 470s. Perhaps Athenian craftsmen and merchants felt as if they required guarantees that these foreigners—other Greeks, Phoenicians, Egyptians, etc.—were not going to take over their businesses or dilute their citizen benefits. These benefits were increasing after the 460s, benefits such as pay for jury duty, pay for assembly work, grain distributions, and subsidies for the theatre.16 There may also have been a little bit of fear on the part of Athenians that immigrants to Athens, especially political exiles with some wealth who looked to settle more permanently, would marry their daughters to Athenians, diminishing marriage prospects for their own daughters. There are a variety of reasons why the law was written and passed.

All this speculation on Athenian motivations must be understood within the context of the evolution of ethnographic thinking in the fifth century and the circumstances that led Greeks to distinguish more precisely between both themselves and non-Greeks and between Greeks and other Greeks. Whereas most scholars see the drive towards a Panhellenic identity as essential to the fifth century, the evidence of the failure of any coherent concept of Greekness actually emerging permeates Herodotus, the local historians and genealogists, Athenian public art, and inter-polis practices especially between the 460s and 370s. The Citizenship Law was another manifestation of the tension between being Greek and being of a certain polis. Whatever Panhellenism the Persian Wars may have engendered in the Greeks, the Athenian archê moved a long way towards suppressing it, at least in Athens.

Patterson links the Citizenship Law to increased immigration and suggests that the establishment of metoikia was also related. It is nearly impossible, however, to establish whether mass immigration occurred at a scale where it could have been the primary factor, especially with respect to the numbers and immigration patterns for metic women. The demographics of the period between 480–450 BCE are tenuous at best and Patterson gives what is still the most thorough attempt at reckoning citizen numbers (and total population by extension) in Athens in this period.17 According to her analysis, the Athenian citizen population doubled between 480–450 BCE, in no small part due to “non-natural increase,” meaning immigrants being admitted into the ranks of citizens.18 If we believe Duncan-Jones’ analysis using the same statistics for numbers of metics, the total male metic population in Athens around the beginning of the Peloponnesian War in 431 BCE was roughly 12,000,19 although Whitehead notes that this was likely the high point and numbers in the fourth century after the war never again reached this level.20

Duncan-Jones’ number does not include women or men beyond military age and so we should consider what bearing this has on our subject. Whitehead says that women would not noticeably impact the number much because, “the number of such women was small,” especially of independent metic women.21 And yet this is precisely the population that was most affected by the Citizenship Law, more so than any Athenian family or metic man. Can we say anything about the number of metic women in Athens in this period and why a law primarily affecting them and their children would be passed?

In the middle of the fifth century, Athens was thriving, a developing economic center and a regional hegemon. It would make sense for large numbers of people looking for work to be drawn to it, even independent women who might find work as prostitutes, nurses, musicians, or other professions. If we imagine that the Citizenship Law was designed to address a problem of inc...