eBook - ePub

Social Stress and the Family

Advances and Developments in Family Stress Therapy and Research

- 231 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Social Stress and the Family

Advances and Developments in Family Stress Therapy and Research

About this book

An informative anthology of recent theory and research developments pertinent to family stress.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Social Stress and the Family by Hamilton I Mc Cubbin,Marvin B Sussman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

The Family Stress Process: The Double ABCX Model of Adjustment and Adaptation

Hamilton I. McCubbin is Professor and Head and Joan M. Patterson is a Research Associate, Department of Family Social Science, University of Minnesota, St. Paul.

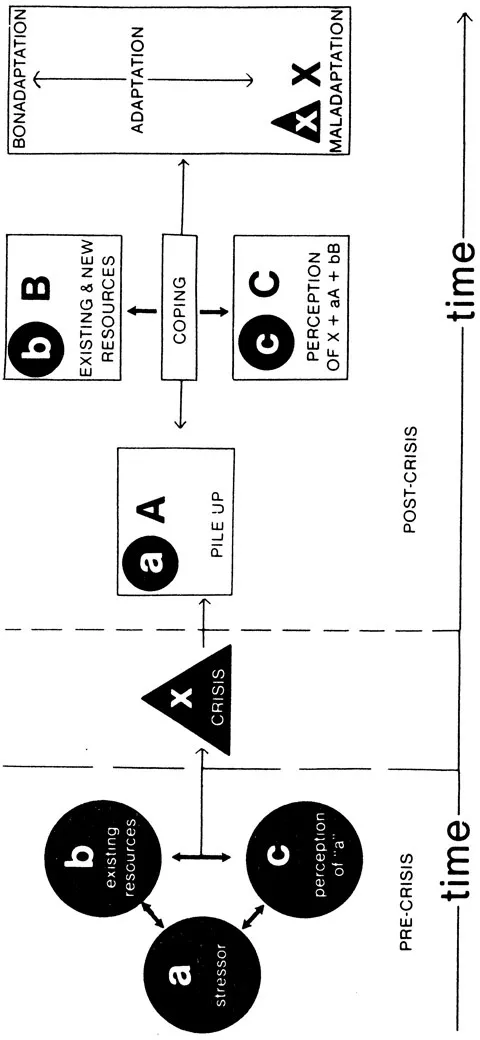

In reviewing family stress research since the advent of Hill’s ABCX family crisis model (1949, 1958) and Burr’s (1973) synthesis of family stress research (McCubbin, Joy, Cauble, Comeau, Patterson, & Needle, 1980; see Klein, Chapter 4), it would appear that family outcomes following the impact of a stressor and a crisis are the by-product of multiple factors in interaction with each other. This would suggest that one productive research and theory building strategy for studying family adaptation to normative and non-normative crises would be to employ a multivariate model where psychological, intra-familial, and social variables identified from prior family stress studies would be addressed simultaneously. By so doing, the individual and collective contributions of these variables could be ascertained. The central research questions for family stress investigations then become how much and what kinds of stressors; mediated by what personal, family, and community resources and by what family coping responses; and what family processes shape the course and ease of family adjustment and adaptation over time. This chapter addresses these issues by using longitudinal observations of families under stress to advance our understanding of the family stress process which includes the Double ABCX framework (McCubbin & Patterson, 1982; in press) and the family processes of adjustment and adaptation.

The Hill ABCX Model Redefined

Family scholars have attempted to identify the variables which account for the observed differences among families in their positive adaptations to stressful situations. The earliest conceptual foundation for research to examine this variability has been the Hill (1949; 1958) ABCX family crisis model:

A (the stressor event)—interacting with B (the family’s crisis meeting resources)—interacting with C (the definition the family makes of the event)—produce X (the crisis).

Family Demands: Stressor and Hardships (a Factor)

In an effort to render clarity to the ABCX model and to establish a link to physiological (Selye, 1974) and psychological (Lazarus, 1966; Mikhail, 1981) concepts of stress, we define a stressor as a life event or transition impacting upon the family unit which produces, or has the potential of producing, change in the family social system. This change may be in various areas of family life such as its boundaries, goals, patterns of interaction, roles, or values. Family hardships are defined as those demands on the family unit specifically associated with the stressor event. An example of hardships would be the family’s need to obtain more money or to rearrange family work and recreation plans to accommodate the increased medical expenses and the demand for home care of a handicapped member. Both the stressor and its hardships place demands on the family system which need to be managed.

Family Capabilities: Resistance Resources (b Factor)

The b factor, the family’s resources for meeting the demands of a stressor and hardships, has been described as the family’s ability to prevent an event of change in the family social system from creating a crisis or disruptiveness in the system (Burr, 1973). Resources, then, become part of the family’s capabilities for resisting crisis. Angell (1936), one of the early theorists attempting to describe more specifically what constituted family resources, emphasized the value of family integration, that is, the thorough family life, of which common interests, affection, and a sense of economic inter-dependence are perhaps the most prominent; and family adaptability, that is, the family’s capacity to meet obstacles and shift its course of action. Cavan and Ranck (1938) and Koos (1946) identified additional resources of family agreement about its role structure, subordination of personal ambitions to family goals, satisfactions within the family obtained because it is successfully meeting the physical and emotional needs of its members, and goals toward which the family is moving collectively. Hill (1958) summarized the b factor as “adequacy-inadequacy of family organization.”

Family Definition: Focus on Stressor (c Factor)

The c factor in the ABCX Model is the definition the family makes of the seriousness of the experienced stressor. There are objective cultural definitions of the seriousness of life events and transitions which represent the collective judgment of the social system (see Reiss & Oliveri, Chapter 3), but the c factor is the family’s subjective definition of the stressor and its hardships and how they are affected by them. This subjective meaning reflects the family’s values and their previous experience in dealing with change and meeting crises. A family’s outlook can vary from seeing life changes and transitions as challenges to be met to interpreting a stressor as uncontrollable and a prelude to the family’s demise.

Family Tension: Stress and Distress

Stressor events and related hardships produce tension in the family which needs to be managed (Antonovsky, 1979). When this tension is not overcome, stress emerges. Family stress (as distinct from stressor) is defined as a state which arises from an actual or perceived demand-capability imbalance in the family’s functioning and which is characterized by a multidimensional demand for adjustment or adaptive behavior. Stress, then, is not stereotypic, but rather varies depending upon the nature of the situation, the characteristics of the family unit, and the psychological and physical well-being of its members. Concomitantly, family distress is defined as an unpleasant or disorganized state which arises from an actual or perceived imbalance in family functioning and which is also characterized by a multidimensional demand for adjustment or adaptive behavior. In other words, stress becomes distress when it is subjectively defined as unpleasant or undesirable by the family unit.

Family Crisis: Demand for Change (x Factor)

These factors taken together: (a) the stressor event and hardships; (b) the family’s resources for dealing with stressors and transitions; (c) the definition the family makes of this situation; and (d) the resulting stress or distress, all influence the family’s resistance, that is, its ability to prevent the stressor event or transition from creating a crisis. Crisis (the x factor) has been conceptualized as a continuous variable denoting the amount of disruptiveness, disorganization, or incapacitatedness in the family social system (Burr, 1973). As distinct from stress, which is a demand-capability imbalance, crisis is characterized by the family’s inability to restore stability and by the continuous pressure to make changes in the family structure and patterns of interaction. In other words, stress may never reach crisis proportions if the family is able to use existing resources and define the situation so as to resist systemic change and maintain family stability.

Longitudinal Observations of Families in Crisis: Emerging Concepts

The Hill ABCX framework was used initially to guide a longitudinal study of families which had a husband/father held captive or unaccounted for in the Vietnam War. Observations of the 216 families in crisis, precipitated by the prolonged absence (average 6.6 years) of fathers, revealed at least four additional factors which appeared to influence the course of family adaptation over time: (a) the pile-up of additional stressors and strains; (b) family efforts to activate, acquire, and utilize new resources from within the family and from the community; (c) modifications in the family definition of the situation with a different meaning attached to the family’s predicament; and (d) family coping strategies designed to bring about changes in family structure in an effort to achieve positive adaptation. In addition, observations from this longitudinal study suggested that, over time, families go through phases of adjustment and adaptation characterized by different processes in which these factors interact.

In previous publications (McCubbin, Olson, & Patterson, in press; McCubbin & Patterson, 1982; in press), we have used these observations to advance a Double ABCX Model of family behavior (see Figure 1) which uses Hill’s original ABCX model as its foundation and adds post-crisis variables in an effort to describe: (a) the additional life stressors and strains which shape the course of family adaptation; (b) the critical psychological, intra-familial, and social resources families acquire and employ over time in managing crisis situations; (c) the changes in definition and meaning families develop in an effort to make sense out of their predicament; (d) the coping strategies families employ; and (e) the range of outcomes of these family efforts.

In this chapter, we will describe the components of the Double ABCX Model with select observations from these 216 families which provide the inductive support for this line of theory building.

This description will be followed by an expansion of the Double ABCX Model which identifies, describes, and integrates the process components of family behavior in response to a stressor and to a family crisis. This family stress process is called the Family Adjustment and Adaptation Response—FAAR.

Family Demands: Pile-up (aA Factor)

Because family crises evolve and are resolved over a period of time, families seldom are dealing with a single stressor, but rather, our longitudinal data suggest they experience a pile-up of stressors and strains (i.e., demands), particularly in the aftermath of a major stressor, such as a death, a major role change for one member, or a natural disaster. This pile-up is referred to as the “aA” factor in the Double ABCX Model. These demands or changes may emerge from (a) individual family members, (b) the family system, and/or (c) the community of which the family and its members are a part.

There appear to be at least five broad types of stressors and strains contributing to a pile-up in the family system in a crisis situation: (a) the initial stressor and its hardships, (b) normative transitions, (c) prior strains, (d) the consequences of family efforts to cope; and (e) ambiguity, both intra-family and social.

Stressor and its hardships. Inherent in the occurrence of a stressful event such as a husband/father being reported as missing or a prisoner of war are hardships which increase and possibly intensify as the stressor situation persists or is unresolved. Wives in our longitudinal study, whose husbands were absent, were taxed with both the traditional and inherited responsibilities of the dual mother-father

FIGURE 1. The double ABCX model

role (McCubbin, Hunter, & Metres, 1974) which required solo decision making, disciplining of children, handling family finances, and managing children’s health problems. Many wives experienced anxieties, frustrations, and feelings of insecurity and showed emotional symptoms of strain with the extended absence and uncertainty of their spouses’ returns. Hardships, such as these, often are not readily resolved (as was true for these wives) and when they persist, they become additional sources of strain contributing to family distress.

Normative transitions. The demands of individual members and the family system are not static but change over time. For example, these families experienced the normal growth and development of child members (e.g., increasing need for independence), of adult members (e.g., mother’s desire to pursue a career), of the extended family (e.g., death of grandparent, births) and family life cycle changes (e.g., school transitions, launching young adults). Such transitions occur concomitantly, but independently, of the initial stressor. These transitions or opportunities also place demands on the family unit since they require change.

Prior strains. It would appear that most family systems carry with them some residue of strain which may be the result of unresolved hardships from earlier stressors or transitions or may be inherent in ongoing roles such as parent, employer, etc. (Pearlin & Schooler, 1978). When a new stressor is experienced by the family, these prior strains are exacerbated and families become aware of them as demands in and of themselves. For example, wives whose husbands were missing became much more aware of the unresolved strains in their relationships with in-laws. Parent-child conflicts, which had existed when fathers were home, were often exacerbated for mothers functioning as single parents. These prior strains are not usually discrete events which can be identified as occurring at a specific point in time but rather, emerge more insidiously in the family. They do, however, contribute to the pile-up of demands families must contend with in a crisis situation.

Consequences of family efforts to cope. The fourth source of pile-up includes stressors and strains which emerge from specific coping behaviors the family may use in an effort to cope with the crisis situation. For example, wives acting as head of the household in their husbands’ absence appeared to become more independent and self-confident. As mother changed her role and strengthened her authority and sought out new sources of emotional support, members of the kin network, especially in-laws concerned about possible divorce, challenged and questioned this style of coping. Their disapproval caused additional strain, contributing to the pile-up.

Intra-family and social ambiguity. Ambiguity is inherent in every stressor since change produces uncertainty about the future. Internally, the family may experience ambiguity about its structure. Certainly, having a spouse missing is most ambiguous in light of the unpredictability of his return. On the basis of systems theory and the symbolic interactionist perspective, Boss (1977) has suggested that boundary ambiguity within the family system is a major stressor since a system needs to be sure of its components, tha...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- CONTENTS

- DEDICATION

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: The Family Stress Process: The Double ABCX Model of Adjustment and Adaptation

- Chapter 2: Critical Transitions Over the Family Life Span: Theory and Research

- Chapter 3: Family Stress as Community Frame

- Chapter 4: Family Problem Solving and Family Stress

- Chapter 5: Individual Coping Efforts and Family Studies: Conceptual and Methodological Issues

- Chapter 6: Social Support and Family Stress

- Chapter 7: Contribution of Personality Research to an Understanding of Stress and Aging

- Chapter 8: Family Divorce and Separation: Theory and Research

- Chapter 9: Mundane Extreme Environmental Stress in Family Stress Theories: The Case of Black Families in White America

- Chapter 10: Analytic Essay: Family Stress and Bereavement

- Chapter 11: Researching Family Stress