eBook - ePub

Positivism, Presupposition and Current Controversies (Theoretical Logic in Sociology)

- 234 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Positivism, Presupposition and Current Controversies (Theoretical Logic in Sociology)

About this book

This volume begins by challenging the bases of the recent scientization of sociology. Then it challenges some of the ambitious claims of recent theoretical debate. The author not only reinterprets the most important classical and modern sociological theories but extracts from the debates the elements of a more satisfactory, inclusive approach to these general theoretical points.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Positivism, Presupposition and Current Controversies (Theoretical Logic in Sociology) by Jeffrey Alexander in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

THEORETICAL LOGIC IN SCIENTIFIC THOUGHT

The attempt to elaborate a general theoretical logic for sociology is confronted by two barriers. There is, of course, the truly imposing lack of agreement on what the general theoretical issues are and how they affect sociological formulations. I will discuss this issue in chapters 2 and 3. But before this problem can even be addressed, there is another obstacle which must first be overcome. This is the issue of theoretical thinking itself, not “how” general issues affect sociology but “whether” they do. Since sociology has for the most part measured itself against the standard of the natural sciences, the point at the center of this initial problem becomes the debate over the nature of science. If the independent role of general thinking in sociology is to be preserved, it is necessary to reinterpret the conventional understanding of the scientific process.

In the first section of this chapter, I present the outline of such a reformulation. Next, I articulate the principles of the prevailing “positivist persuasion,” found in the work of a wide range of contemporary sociologists. In subsequent sections, I argue, first, that the traditional alternative to such positivism, the argument that sociology should not be conceived as a science, represents an inappropriate response, and I propose instead a series of counterpostulates to the positivist conception of science, counterpostulates derived from the work of those philosophers and historians who, rather than leave science to its objectivist interpreters, have begun to develop an alternative understanding of natural science itself. In conclusion, I present the case for developing a conception of general theoretical logic in sociology.

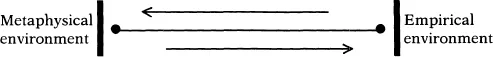

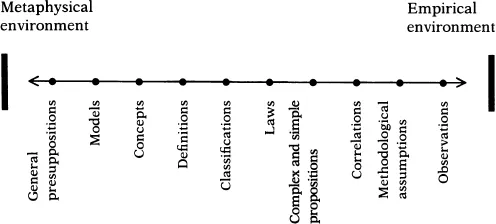

1. INTRODUCTION: SCIENTIFIC THOUGHT AS A TWO-DIRECTIONAL CONTINUUM

Science can be viewed as an intellectual process that occurs within the context of two distinctive environments, the empirical observational world and the non-empirical metaphysical one. Although scientific statements may be oriented more toward one of these environments than the other, they can never be determined exclusively by either alone. The differences between what are perceived as sharply contrasting kinds of scientific arguments should be understood rather as representing different positions on the same epistemological continuum (see fig. 1).1† Those scientific statements closer to the right-hand side of the continuum are said to be “empirical” because their form is more influenced by the criterion of precisely describing observation, hence the “specificity” of empirical statements. Statements closer to the left-hand side are called “theoretical” because their form is concerned less with the immediate character of the observations that inform them. One can, in fact, arrange all the different components of scientific thought in terms of such degrees of generality and specificity (fig. 2).2† This listing is intended to be suggestive rather than exhaustive, an attempt to order the elements most often mentioned in the social scientific literature as constituting independent points of focus. Each of these elements I have listed could themselves be further elaborated—for example, the methodological level into “meta-methodological assumptions” and “technical orientations.” Also, the identity of different levels differs, to some degree, according to the nature of the scientific activity. In the human sciences, the category of “general presuppositions” should be divided into “presuppositions” and “ideological assumptions,” whereas this division does not apply to the sciences of nature.

Figure 2 allows us to make several important points. First, it clarifies further the relative character of the theory/data split. That “data” is a thoroughly relative formulation can be illustrated by the fact that as social scientists we continually treat as data the more general “scientific” formulations of those around us—others’ propositions, models, classifications, and general assumptions about the empirical world. But it is also clear that “theory” is just as much a designational convenience. Different sociological theorists, like Talcott Parsons, John Rex, or Hans Zetterberg, take different levels of scientific formulation to be indicative of “real scientific theory” as distinguished from more general “speculation” on the one hand and mere “data” on the other. Thus, while Parsons defines proper theoretical thinking in sociology as focusing on “frames of reference” (i.e., general presuppositions) and on “generalized conceptual systems,” Rex considers the “model” to be the level of generality at which any truly effective sociological theory must be directed.3 And in sharp contrast to both of these theorists, Zetterberg claims the only legitimate focus for social scientific theorizing to be “multi-variate” axioms, as compared with mere simple propositions, on the one hand, and more general “social thought,” on the other.4† Although data and theory are, thus, commonly equated with qualitative positions on the more specific and general sides of the scientific continuum, it is more correct to understand them as quantitative distinctions: every formulation “leftward” of any given point of focus is called theory and every statement “rightward” of that point is claimed as data.

Figure 1

THE CONTINUUM OF SCIENTIFIC THOUGHT

Figure 2

THE SCIENTIFIC CONTINUUM AND ITS COMPONENTS

As this first clarification begins to indicate, the continuum conceptualization also allows us to emphasize the interdependence of formulations at each of these levels. Although common sense and a certain body of scientific opinion inform us that these elements are qualitatively discrete, that is, completely independent of one another, in positioning the elements on this continuum I try to demonstrate precisely the opposite. “Generality” and “specificity” indicate orientations, or directions, of different kinds of scientific statements, but each element nevertheless contains references to both general and specific, empirical and nonempirical, properties. If these elements actually were completely qualitatively differentiated, they would represent “concrete” distinctions. They are, instead, “analytic” distinctions, separations established for the convenience of scientific discourse, made to facilitate communication and not to establish ontological qualities.

Every piece of actual scientific analysis contains implicit references to, and is at least influenced by, each of the other analytic levels of scientific thought. What appears, concretely, to be a difference in types of scientific statements—models, definitions, propositions—simply reflects the different emphasis within a given statement on generality or specificity. Even the most metaphysical theory of society, which explicitly focuses upon and elaborates only the most general properties, is influenced by implicit though undeveloped notions of models, propositions, and empirical correlations. Similarly, even for the most self-consciously neutral and precise scientific exercise, “empirical observations” represent only an explicit focus.5† Generalized presuppositions, definitions, classifications, and models—all levels influenced by more metaphysically oriented concerns—still affect such specific statements, even though their influence remains completely implicit.

This last point raises a final issue. While the continuum notion allows one to stress the interdependence of each analytical level, it illustrates also that these relationships are asymmetrical. This is implied by the very notions of generality and specificity: while elements at lower levels bring new information about observable reality to bear, they still represent specifications of more general assumptions. The general always subsumes the specific. Yet this asymmetry does not mean generality is more important. For science, especially, this is not the case. By themselves, “metaphysical” statements are not scientific, neither are models or definitions; each has scientific relevance only when coupled with commitments which are determined more directly by the empirical environment. Scientific status assures—to lift a phrase from Toulmin’s early work—that “statements at one level have a meaning only within the scope of those in the level below.”6 It must be emphasized, then, that although the asymmetry of the scientific continuum has important implications, this intellectual hierarchy is not, for science, a hierarchy of relative importance, nor does it imply temporal priority for the allocation of scientific activity.

Although social and natural scientists continually do make imperial claims for the greater heuristic fruitfulness and determinate power of each of these different levels of analysis, it is more correct to regard every level as having its own partial autonomy. While the boundaries of each element are established by the “empirical” and “nonempirical” formulations on either side, each level performs a distinctive type of intel lectual function and is subject for this reason to distinctive criteria of scientific merit. Only by understanding science in this manner can we preserve both the general and specific dimensions of scientific thought.

2. THE POSITIVIST PERSUASION IN SOCIAL SCIENCE: THE REDUCTION OF THEORY TO FACT

The position I have just articulated represents a minority viewpoint, and a steadily shrinking one, among American sociologists today. At least since the end of the Second World War, there has been a growing tendency toward conceptualizing and practicing social science as a one-directional process, as an inquiry that moves, in terms of the framework I have presented, only along the dimension from specificity to generality.7† I will call this tendency the positivist “persuasion” because in the context of contemporary sociology it represents much more of an amorphous self-consciousness than an articulate intellectual commitment; indeed, the formal methodological principles of classical positivism are today eschewed by most sophisticated sociological thinkers. Yet positivism in a more generic sense is, nonetheless, a persuasion that permeates contemporary social science.8 In this section I will outline and elaborate its general postulates, and indicate what I regard as its debilitating ramifications.

The two postulates central to the positivist persuasion are, first, that a radical break exists between empirical observations and nonempirical statements, and, second, that because of this break, more general intellectual issues—which are called “philosophical” or “metaphysical”—have no fundamental significance for the practice of an empirically oriented discipline. The third postulate, which completes what might be called the triadic foundations of the positivist orientation, is that since such an elimination of the nonempirical reference is taken to be the distinguishing feature of the natural sciences, any true sociology must assume a “scientific” self-consciousness.9†

These first three fundamental propositions—unlike the fourth postulate, which I will discuss below—have in one form or another assumed such a self-evident role in much of contemporary sociology that they are rarely articulated. Perhaps the best illustration of how they do in fact present a logically interrelated perspective is provided by William R. Catton, Jr., whose book From Animistic to Naturalistic Sociology combines arguments about the history and philosophy of science with actual empirical practice in a manner that typifies the self-understanding of most American empirical sociology today. Contrary to the two-directional position outlined above, Catton defines “the issue of supra-empirical postulates” as the decisive distinction between scientific and nonscientific intellectual disciplines.10 He locates the origins of the modern sociological discipline in the transition from the subjective study of society typified by such disciplines as philosophy and theology—pejoratively defined as “animistic” approaches—to what he considers the purely “naturalistic” approach, in which the investigator’s commitments have no influence on his or her data and in which generalizations are based solely on objective evidence. On the basis of this perspective on contemporary sociology, Catton dismisses traditional epistemological and ontological issues on the grounds that “the operationally real is the observable,” referring, for example, to the debate about materialism in the following manner: “Genuinely naturalistic sociology would simply say that there is no operationally verifiable meaning to the dichotomy ‘material reality’ versus ‘immaterial reality.’”11

Although the starkness of these formulations represents Catton’s commitment to the radically positivist perspective of operationalism, in a more general and less sectarian form his conception of the nature of the sociological science is widely shared. For example, although Hans Zetterberg views himself as in battle with operationalism and with narrowly empiricist views of sociological theory, his book On Theory and Verification in Sociology became a minor classic on the strength of its argument for a “‘scientific’ conception of sociological theory” which can finally establish the separation of the concerns of “social thought” from those of social science.12

And to move one step further along the scientific continuum, even such a purposefully theoretical sociologist as William J. Goode lends his support to the foundations of the positivist perspective on science. In the introductory chapter to his collection of theoretical essays, Goode emphasizes what he considers the irrelevance of generalized metaphysical concerns to contemporary sociology. Although the “common philosophical position has argued that the biases of human observers … will always prevent any security about the conclusions the sociologist reaches if they are based on observation,” Goode writes, this issue has been, and should continue to be, of little concern to the working sociologist.13 “It is sufficient merely to note,” he continues, “that most sociologists now concern themselves very little with this question. … Their general position is that there are no fundamental methodological or epistemological problems that cannot be solved in principle.”14 Goode justifies what I have called this second positivist postulate by proclaiming his faith in the first, in the radical separation of empirical and nonempirical dimensions: “Sociologists have been correct in adopting (along with their scientific forebears) the pragmatic position that since they are indeed developing analyses which do seem to correspond with the reality they perceive, the problems cannot be overwhelming.”15 As this latter statement indicates, Goode links these two positions to the identification of sociology with natural science, a connection that completes his articulation of the triadic foundations of the positivist persuasion. “The epistemological assumptions and canons of science in other fields,” he writes, “are thought to be completely applicable to the study of social behavior.”16†

The fourth and final postulate of the positivist persuasion continues and in a certain sense completes the intellectual thrust of the three principles that form its foundation. It posits that in a science from which “philosophical” issues have been excluded and in which, correspondingly, empirical observation is thoroughly unproblematic, questions of a theoretical or general nature can correctly be dealt with only in relation to such empirical observation. Although definitions about exactly what constitutes theory and data must, for the reasons discussed in section 1, remain fluid, there has been a continual and relentless effort in sociological discussion to reduce every theoretical whole to the sum of its more empi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Preface and Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Table of Contents

- Chapter One: Theoretical Logic in Scientific Thought

- Chapter Two: Theoretical Logic in Sociological Thought (1): The Failure of Contemporary Debate to Achieve Generality

- Chapter Three: Theoretical Logic in Sociological Thought (2): Toward the Restoration of Generality

- Chapter Four: Theoretical Logic as Objective Argument

- Notes

- Author-Citation Index

- Subject Index