![]()

Part I

Meeting challenges in programmes and service delivery

![]()

Realizing self-reliance through microfinance

Alex Pollock1

Introduction

The first clause in the title of this chapter – ‘Can the subaltern pay?’ – is merely rhetorical,2 since it is widely acknowledged that each year tens of millions of poor and low-income clients across the globe repay loans to thousands of microfinance institutions, most often with lower default rates and less risk than wealthier clients with access to formal banking services. In the context of the diverse global setting of the microfinance industry, most microfinance practitioners and stakeholders habitually refer to microfinance clients as poor and/or low-income people and households. Although largely true, such consumption and income type descriptors give little indication of the economic, social, status, class or ethnic identifiers of the typical clients of microfinance institutions, who are very often from the subaltern segments of society in social formations where market relations are asymmetric, unevenly developed and often very shallow.

As subalterns, they are most often from poor and low-income communities, composed of a multiplicity of economic actors in societies with specific social and cultural cleavages, whether they be peasant farmers, smallholders or animal herders; itinerant hawkers or market traders; artisans or self-employed tradespersons; women home-workers or microentrepreneurs; microenterprise owners with family businesses, sole-proprietorships or employees. They also include refugees, immigrants, women, youth and the aged, as well as workers and low-paid salaried employees in the private sector and in government service.

Ethnographically and sociologically diverse, subaltern microentrepreneurs are more likely to be part of an impoverished sub-proletariat than a mushrooming class of aspiring capitalists (Nevin 1982). Many, if not most, eke out a living from informal enterprises on the marginal pole of the economy trying to keep their families above the breadline. The microentrepreneur’s household is more strategically linked and integrated into the business than formally regulated enterprises where the market and the household are more distinct, although the formal family-owned small businesses often employ unpaid or low-paid family workers. But while the son or sons in the family business will inherit the formalised family enterprise, trans-generational ownership of subaltern enterprise is less common as they are often shortlived, with the owners changing businesses between bouts of employment and unemployment.

While very different from each other, with diverse subjectivities, they typically live and work in the hinterland and margins of economic and social life, where they are excluded from access to the formal financial system and participation in the modern economic sector.3 Those engaged in manufacturing enterprises often work in unregulated and highly competitive informal sectors of the economy, maintaining pre-Taylorist enterprises of low asset value, utilising aged factors of production that require low-skilled, labour-intensive manpower. Many women home-workers are engaged in self-regulated and self-paced subsidiary income-generating activities such as food-processing, small animal husbandry and craftwork that brings in supplementary income to households, but many others work under highly extractive semi-industrial regimes in their homes that demand long working hours and intensive productivity that links them to global markets for cheap consumer goods. In some regions, such home-workers may be engaged in decades-old pre-modern putting-out systems controlled by local merchants.

While microenterprises involved in commerce and trade often face intense competition in conditions of market saturation from an abundance of identical businesses in restricted markets, where absolute value is finely whittled and spread among traders and enterprises. Women microentrepreneurs are often particularly vulnerable in such markets due to a lack of social and economic bargaining power, although they often make up for this through networks of solidarity and collective action with each other. Such subalterns remain caught in the economic interstices of modernity where they are bypassed by its economic opportunity, alienated from financial markets and trapped in low income and poverty. They are even more unfortunate if they are caught in the web of civil war, ethnic or colonial conflict which makes their subaltern state even more economically tenuous and their lives precarious.

Unlike many humanitarian, human development and other pro-poor interventions, the ethos of microfinance puts subaltern economic agency, self-determination and self-help at the core of its vision, which requires understanding and recognition of the divergent and marginal character of subaltern economies. This has enabled microfinance to develop successful credit methodologies, loan products and other services that treat subaltern economies as distinct market segments requiring specific financial interventions with products capable of creating inclusive financial services that can help the subaltern become self-reliant. This is achieved by giving them financial resources that they can use to run their own small enterprise or create self-employment that enables them to feed and clothe their families.4

Microfinance is a sustainable – operationally and financially self-sufficient – market-based approach to providing financial resources to subalterns to assist them realise their own self-reliance.5 As market-based microfinance has grown, an increasing number of best practice institutions have developed economies of scale that enabled them to become sustainable and profitable undertakings, with many submitting their financial data and audited financial statements to the Microfinance Information Exchange (MIX Market) – an international project that benchmarks financial performance of microfinance institutions against a series of financial performance and efficiency ratios. Thus, by December 2009, the 1,873 microfinance institutions participating in MIX had 90.2 million clients with a gross loan portfolio of USD 64.8 billion, deposits of USD 26.7 billion and an average loan balance of just USD 527 per borrower.6

Since its inception, the global microfinance industry has been built by financing from local philanthropists, international non-governmental organisations (NGOs), government donors and multilateral agencies. But it has also been financed by social investors and specialised ethical investment funds interested in helping the poor and poorest through sustainable and self-reliant institutions. With a burgeoning reputation for financial effectiveness, the more profitable segments of the industry are now being conceived by some in the regular international finance sector as an emerging market able to offer asset class investments capable of producing significant returns for individual and institutional investors (Rosenberg, 2007).7

In a world replete with development assistance failures, despite its many detractors, microfinance has been a global success story. Yet despite its remarkable growth across the globe, in most regions of the world, national bankers and the formal finance sector still habitually view microfinance clients as high-risk borrowers whose hazard is best mitigated by their exclusion from the credit services of the formal financial system.8 As far as the traditional banking sector is concerned, subalterns are a classic sub-prime market segment engaged in insecure and unstable economic activities that is best left to pawnbrokers, money-lenders and other informal and non-formal financial intermediaries.

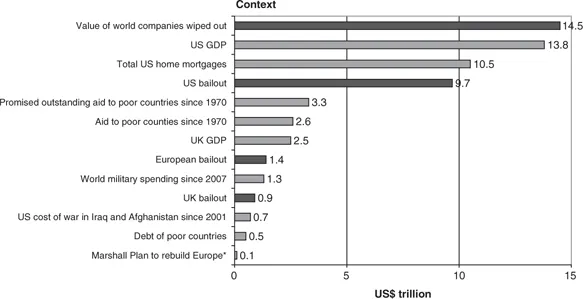

In this context, it is interesting to contrast the ongoing predicament of the global finance system with the increasing vitality of the international microfinance industry. While the global activity of the international microfinance sector goes from strength to strength, the global finance system continues to reel from the aftershock of calamitous financial overreach into sub-prime real estate markets through a variety of opaque investment instruments by senior commercial banks and financial institutions in the USA, UK and northern Europe that resulted in a collapse of major financial conglomerates, which necessitated western governments digging deep into the pockets of their taxpayers to finance bailouts valued at USD 9.7 trillion in the USA and USD 2 trillion in Europe. According to Bloomberg some 33 per cent of the value (or USD 14.5 trillion) of the world companies were wiped out as a result of the crisis. The US government financed rescue package was almost equivalent to the total value of home mortgages in the USA, while the UK package was equivalent to over a third of British GDP.

Figure 1.1 Global financial crisis: losses and bailouts for US and European countries in context

While the complex institutional interconnectedness of banks, stock markets, investment companies and brokers and the multiple failures that led to this financial crisis – including the misperceptions and myopia of investors, rating agencies and regulators – should caution against any simple comparison between international high finance and microfinance. However, the simple fact remains that many grand financial institutions have been ruined and public finances wrecked by financial overstretch into high risk sub-prime markets, while the global microfinance industry has grown exponentially over the past decades by focusing specifically on such markets. The key difference being those microfinance institutions and their staff know their subaltern customers personally and are knowledgeable of their markets, finances, businesses, families and communities. This is based on close individual relationships where risk is assessed palpably and directly, not packaged through instruments and procedures that may hide rather than disclose risk.9

The development of microfinance

Different forms of what is now called ‘microfinance’ have been around for centuries, often organised by subalterns themselves, whether in the form of mutual funds collected by artisans and workers through guilds and trade associations for their members; in the form of cooperative marketing or bulk procurement of farm inputs by peasant farmers and smallholders; or through rotating savings and credit associations (ROSCAS).10 Such informally contracted alliances are not primarily based on law but on the principles of solidarity, fraternity, mutuality and trust.

While subaltern finance initiatives are ubiquitous, it was only as a result of breakthroughs achieved in credit lending methodologies in Latin America and South East Asia in the 1970s that microfinance has gradually assumed a prominent role in development assistance, where it is perceived as a large-scale, high-impact development tool contributing to mitigating poverty, promoting self-reliance and encouraging economic growth through financing the smallest and most marginal businesses and households (Otero and Rhyne 1994).11 The popularisation of subaltern microcredit owes much of its reputation to the inspirational work of Muhammad Yunis and the Grameen Bank, which each year provides millions of loans to the Bangladeshi poor.12 The Grameen Bank offered one of the first models of large-scale credit delivery to the very poor that is still being copied in many of the poorest regions of...