![]()

Part One

International Precious-Metal Production and Distribution, 1670–1770

![]()

Chapter One

The South and Central American mining ‘crisis’

For a century prior to c. 1670 South and Central American silver production had dominated international specie markets. The delicate price equilibrium between product (silver and copper) and input (lead) markets, upon which the fortunes of the previously dominant central European Saigerhändler had depended, was seriously disturbed. From about 1570–1670 central European production had declined and in its place there had emerged a series of independent industries — Swedish copper, British lead, and Latin American silver — which operated within autonomous market structures.1

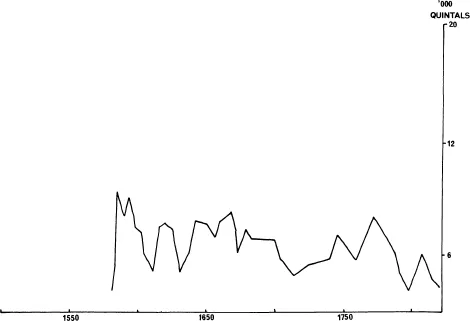

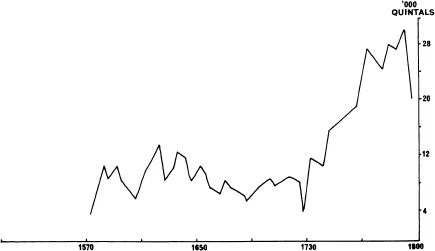

The principal cause of these changes, which established a Latin American hegemony over international gold and silver markets, lay in the introduction of a new technology — the amalgamation process — into the silver industry, which not only resulted in input substitution, shattering the symbiotic relationship between the lead and silver—copper producers by substituting a new input supply system distributing mercury to the main mining centres, but also gave birth to an entirely new industrial resource base exploiting silver haloids (argentite and cerargyrite), almost unknown in Europe, but abundantly available in the New World.2 Initially introduced from the Old World, where it had long been employed in gold production and from the fourteenth century had been utilized in the reduction of Austrian native silver ores to resolve input supply problems caused by the lead crisis of the early 1550s, the new technology’s early history had been a highly chequered one.3 Born of market conditions characterized by high lead prices, stabilization in this metal’s price, and an enhancement in the cost of mercury from the main workings at Almaden had doomed Latin American production during the years 1557–72 to a severe crisis.4 From about the 1570s, however, the advantages of the new technological nexus became apparent. Supply bottlenecks in the Old World mercury mine were resolved as the New World was called in to redress the balance, and the cinnabar deposits of Huancavelica, discovered by the Spaniards in 1564, were opened up. For more than two decades the shallow, open-cast workings of la Descubridora provided a cheap and plentiful supply of the liquid metal (figures 1.1 and 1.5), allowing the Ibero-American silver producer to sweep all before him.5 A new production pattern had been established which would imprint its stamp upon the industry for the next quarter of a millennium. Freed from its subordination to the Old World sources of mercury by the abundant supplies of the liquid metal which issued forth from the mines of Huancavelica, the Latin American industry now realized the full potential of the new technology. The range of exploitable ores was extended, as the new silver haloids containing between 15 and 225 ounces per ton of ore, which had previously been unresponsive to smelting techniques because of their ‘dryness’, were worked and extraction rates were enhanced beyond the 40 per cent levels of the Old World cupelation processes to about 70 per cent of the ores’ metallic content (figure 1.6).6 Rich ores and high extraction rates thus allowed Latin American producers to create abundant quantities of cheap silver which, from about 1570, became not only the principal source of European supply but, passing on, also served to provision Asiatic markets.7

Adoption of the new technology had thus established the Latin American producers’ dominance of world specie markets, but it had also rendered them dependent upon the availability of cheap mercury. Having freed itself from its tutelage to one input supplier, the new industry of the 1570s had fallen captive to another. Yet, save for brief periods, at no time during the history of the amalgamation process was the position of South and Central American precious-metal producers in aggregate threatened by protracted shortages in mercury supply (figures 1.1.–1.4).8 As resource-based production cycles of lengthening periodicity succeeded each other, short-term inter-cyclical crises always gave way to production booms superimposed upon a series of long cycles which maintained output at remarkably high levels. As has already been noted, the first of these production cycles, from about 1565–1615, was associated with the opening up of the Huancavelica mine which ensured a phase, lasting more than two decades, when cheap and plentiful supplies of the liquid metal were produced from the open-cast workings, causing production at Almaden to stagnate as price leadership was assumed by the Peruvian mine. The boom did not last, however, and from 1582 the characteristic pattern of resource depletion and increasing costs may be observed at Huancavelica. Price increases in 1583–5 temporarily retarded the process of production decline, limiting the rate of decline in Peruvian output and enhancing output at Almaden, but production from the giant of the Andes was beginning to display marked instability as workmen plunged deeper into the sandstone country rock. From the 1590s the deeper galleries had to be closed down due to the presence of poisonous gas, and in 1607 production, already declining, collapsed with the subsidence of the major workings. The first upswing in mercury production, having attained a maximum output of c. 10,700 quintals a year, thus came to an end in c. 1615 in crisis conditions.9

Figure 1.1 Mercury production: Huancavelica

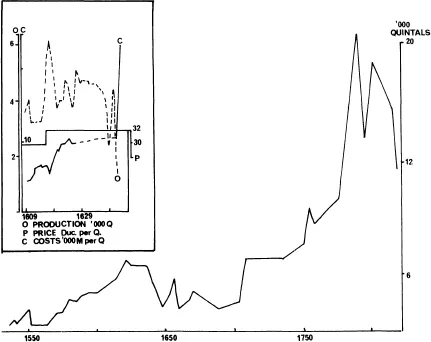

Figure 1.2 Mercury production: Almaden

The Spanish Crown, unwilling to increase prices further and thereby retard silver and gold production, thus cast around for other sources of supply. Not for the last time Peruvian officials looked to China to make up the deficiencies of existing production centres — but without success.10 Seemingly only change from within could lead to a resurrection of the old Ibero-American amalgamated silver and gold mining and metallurgical complex. For the producers at Huancavelica this meant moving into a new high-cost phase of production as the renovation of the workings and the sinking of new ventilation shafts begun in 1609 enhanced production costs. Accordingly, the Crown was faced with either raising prices or being satisfied with diminished levels of mercury production. Neither course of action was acceptable and when the Fugger, anticipating the cost reductions arising from the introduction of the reverbatory furnace at Almaden, offered delivery at seven ducats a quintal below the prevailing price, the Crown leapt at the opportunity. The hopes proffered by the Germans were illusory, however, and after a brief revival at Almaden in 1609 (figure 1.2, inset) production there and in Peru declined until prices were increased in 1615.11

Finally, after an acute, short-term mercury-supply crisis which had induced a dramatic decline in gold and silver production, the Crown had been forced to accept the inevitable.12 With higher mercury prices a broad-based production complex came into existence within which individual production levels initially steadied at an aggregate maximum output level which was slightly higher than before, amounting to some 13,700 quintals a year.13 During this phase in the industry’s history, which encompassed the second production cycle spanning the years 1615–50, the onus of supplying precious-metal producers in the Americas fell once more on Almaden (figure 1.2) whose output was supplemented by the delivery of additional quantities of the liquid metal by successive asientists (Albertinelli, Oberholz, and Balbi) controlling the mines of Idria (figure 1.3).14 Production from these Old World mines, having increased to about 1623, was maintained at a high level to c. 1645, but at no time during the course of the second cycle did their joint output attain the peak levels achieved in Peru during the early 1580s. Even so it was more than sufficient to compensate for the shortfall in production at the reconstructed Huancavelica mine, and at maximum levels of aggregate output in the early 1620s production rose to about 13,700 quintals a year, or nearly 30 per cent more than the previous peak. Once again, however, the boom in the Old World production centres, which had sustained the upswing of the years 1615–23, soon thereafter gave way to decline, production falling at firstly slowly to about 1645 before collapsing in the late 1640s.

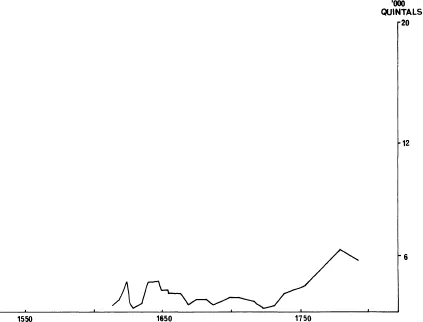

Figure 1.3 Mercury production: Idria

In this instance, however, as the second production cycle drew to its close, there was no abrupt inter-cyclical crisis. Improved market mechanisms allowed a smooth transition to be made between the second and third production cycles. With the restructuring of production at the Peruvian mine after 1642 output from that centre steadily increased to compensate for the decline in the Old World mines. At the peak of this cycle, which ran its course during the years from about 1630–1715, total output amounted to no more than 10,500 quintals a year. In terms of the long cycle, which had witnessed increasing output between the production cycle peaks of 1583 and 1623, attaining a maximum total production level of 13,700 quintals a year at the latter date, the third production-cycle peak in about 1653 merely marked a stage in the long-term production downswing.

The fourth resource-based production cycle, which ran its course in a truncated form between 1690 and 1730, witnessed the culmination of this long-term downward trend in output. Once again, as production at Huancavelica, which had sustained the upswing of the third cycle, finally collapsed after a period of slow and protracted decline, a revival at Almaden paved the way for the transition to the fourth production cycle which attained peak production levels in about 1715 when total output reached about 8,900 quintals a year.

For about 140 years successive production cycles of varying periodicity had been superimposed upon a long cycle which, measured across production-cycle peaks, had witnessed output increase from 10,700 quintals a year in about 1583 to 13,700 in 1623 before declining to 10,500 in 1653 and 8,900 in 1715 (figure 1.4). Throughout this first long phase in its history as a supplier of South and Central American precious-metal producers, the mercury production industry thus clearly revealed a regular and distinctive pattern of production fluctuation and trend associated with endemic resource depletion problems. In each component element of the metallurgical complex (Huancavelica, Almaden, and Idria) production cycles of varying periodicity followed each other upon a trend of rising costs. During each of these cycles, and after a brief phase of intense activity, as miners exploited the richest and most accessible ores, there followed a production downswing, associated with declining ore yields, flooding, or enhanced haulage costs, which precipitated a short-term crisis. Prices rose, resulting in either the opening up of new levels in existing production centres or in an industrial diaspora and the establishment of the industry in a new locus. In either case a new higher cost structure was created, conditional upon lower yielding ores and/or spacially distant deposits. The pattern of fluctuation then repeated itself. Fluctuations thus succeeded each other, at a rate dependent upon the periodicity of the producti-on cycle, upon a trend of rising costs, falling yields and/or geographically more distant workings until the limits of prevailing mining and metallurgical technology were reached when the crisis precipitated by the production-cycle downswing merged into a general crisis.

Figure 1.4 Total mercury production

The production-cycle pattern, described above, is very clearly revealed during the first phase in the industry’s history, spanning the years 1575–1615. After a rapid expansion in output which carried production at Almaden and Huancavelica to a level of some 10,700 quintals a year in about 1583, and sustained it at that amount during the next decade, both workings displayed signs of acute resource depletion. At the ancient mine of Pozo at Almaden the workings were gradually abandoned between 1590 and 1615 having attained a depth of 209 metres and in some places 250 metres, at which point they ceased to be exploitable because of the increase in costs and the difficulties of shoring and draining the galleries.15 At Huancavelica during the same years similar problems were apparent. Here by the late 1590s the principal layer of ore was dipping too deep in the sandstone country rock for the previously dominant open-cast methods of mining to be continued. Miners accordingly began to excavate subterranean workings which, without proper supervision, became labyrinthine in character and subject to penetration by poisonous gases. So bad indeed was the situation in the workings that in 1604 they were temporarily closed. As surface working was resumed, however, the old underground workings posed a major hazard, and when in 1607 one of the galleries was penetrated a major disaster occurred. Heavy rains washed a deluge into the galleries and blocked the main entrance of all the underground workings, bringing production to a halt.16 Thus came to an end the first production cycle, both of the major production centres — at Almaden and Huancavelica — after an initial phase of rapid expansion, being subject to rapidly rising costs, as mines became deeper and ores poorer, which, at prevailing prices, caused production to decline.

Now began the task of renovation. In 1606 work was begun on a major adit to drain the deeper galleries at Huancavelica, and in 1609 a team of experts arrived there from Almaden, under whose supervision ventilation shafts were cut into the dee...